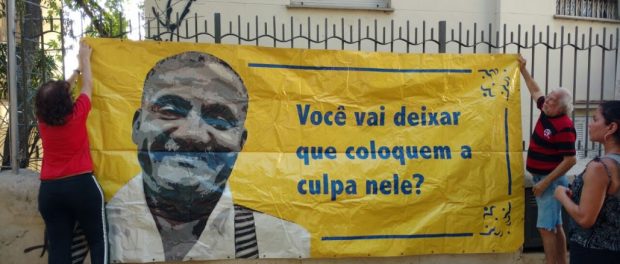

On August 27, 2011, there was a terrible accident on the Santa Teresa tram, or bonde, in the hilltop neighborhood in Central Rio which resulted in serious injuries and several deaths. Among those who died was tram conductor Nelson who had worked for decades on the trams and was well loved by residents. As if it wasn’t enough to have given his life to the trams, Nelson was blamed as responsible for the accident by then Transport Secretary, Júlio Lopes. However the tragedy only occurred because of neglect of the system, which didn’t receive government investment, had a precarious workshop and a total lack of parts. Motivated by love for the trams, workers had to improvise parts so service would not to be interrupted.

At the end of 2011, works on the Santa Teresa tram lines began, though they were halted for over a year after one month of works and 100 meters of progress. Even with a judicial decision which determined the immediate restoration of the tram system, the same pace has been maintained during these last five years of agony. The stretches that have been finished are intermittent–there’s no continuity along the tracks; the stretches are sparse, some without tracks between one place and another, intentionally making circulation unviable.

The same former Transport Secretary, Julio Lopes, decreed that unserviceable assets should be donated to the NGO Rio Solidário. By coincidence, the NGO belongs to Adriana Ancelmo, wife of Sergio Cabral who was Rio state governor at the time of the accident. Ancelmo is also heiress to the transport system as daughter of Jacob Barata, the most powerful businessman in the state’s transport sector, and is a lawyer for Rio’s subway company Metrô-Rio. Our hundred-year-old trams were donated as scrap and the government had nothing to say about it.

Tram for whom?

Currently the trams only go as far as Largo dos Guimarães, as a free service between 11am and 4pm, precisely to avoid the commuting of residents who work and study outside the neighborhood. Only during the Olympics have the authorities approved service beyond these hours, currently 8am-4pm.

The tram now doesn’t go where there are favelas. Costing little, it’s obvious it would be–like it always was–the preferred means of transport for the majority of residents of the neighborhood and there wouldn’t be so much space for visitors. Our tracks now serve merely as promotional marketing, a touristic charm. Where do residents fit into this?… Squeezed inside a bus, obviously… On the tram, together with tourists, clearly not! Where are the stops? Well, the Dois Irmãoes stretch is where the majority of Santa Teresa’s favelas are–Coroa, Fallet, Fogueteiro, Prazeres, Julio Otoni, among others–but our leaders don’t govern for the poor.

In practice, no “politically correct” discourse can override the evidence. The Dois Irmãos route is touristically desirable due to the intended connection with the Corcovado trams leading up to Christ the Redeemer. We’ve already been informed of the State’s plans. According to our leaders, this will be a line without stops taking tourists from the Carioca station in downtown Rio up to Corcovado and back. Hence, it will travel by favelas but will not stop for them.

There’s no queue exclusively for residents and tourists form huge queues, reaching into the hundreds on some days. We don’t have access to our greatest heritage. We’ve been purged and prevented from using our transport, which has become an attraction for tourists and mere decoration in the landscape.

Good things come to those who wait… Really?

The initial official declaration announced that the restoration of the whole system would take six months and be finished before the World Cup. The Olympics have arrived and still nothing’s happened.

The work was initially budgeted at less than R$58.6 million. This then went up to R$87.1 million and has now gone over R$125 million. In April 2016, the State Transport Secretariat approved a further R$27 million to make the works’ conclusion viable, however in June works were once again interrupted due to an allegation of lack of funds.

After five years and double the initially projected costs, the works stopped again. Those of us who live near where works simply stopped over a month ago were left with holes and rubble, like the much anticipated Olympic legacy.

We can’t cross the street. We have no way of taking groceries home, getting help from an ambulance, walking baby strollers, or taking our older people for a walk in the sun. We’re confined like a sandwich filling by the state’s unfinished works and the improvised pen mounted by the City government who installed screens obstructing the rest of the way. We don’t have garages and are fined if we park cars where the City has arbitrarily prohibited access, without listening to residents. There are daily motorcycle accidents and no measures are taken.

Attention: Women working!

Tired of waiting for a miracle, on July 23, three residents decided to get their hands dirty, literally, to prevent any deaths occurring and to guarantee a minimum of access for residents on each side of the street. We bought cement and sand, and with shovels and hoes we decided to fill the holes ourselves, at least the ones in front of our homes. We carried sleepers and gravel. We worked hard and managed to mitigate our discomfort.

Confident that the government’s commitment lacks the will for it to be executed, we took advantage and carried earth to create a garden on the tram tracks. After all, we’ll certainly get to harvest planted herbs if we depend on the speed of the state’s service. Thus the wait will yield fruit, even if it is symbolic and indirect.

The City’s representative, who doesn’t walk the streets to listen to us but circulates to monitor, repress and imp0se his determination, saw us working and called us “pigs” for not recognizing that the pen they built was done with love. It’s an insult to the administrators that we don’t accept the idea of being a meek, enclosed herd. Because we’re not and we really don’t accept this.

Despite the heavy sorrows, we love the tram and this love transcends and goes beyond geographical limits. We’re Santa Teresa residents and we ratify this love. All of us here in the rubble, the residents of other streets, those that live in the favelas and visitors from other places, together we carried earth, brought seedlings, got our hands dirty and cleansed the soul. We’ll make gardens from the debris where we’ll plant ideas and strength too. Our part of the neighbourhood embarked on this madness and decided to bring more people together. If good comes from the bad, the greatest good has been the rediscovery that union creates force. This was just the first seed of our garden in the tracks of shame, and citizenship has flowered.

Before the harvest, however

A few days after the garden was planted, however, on July 27, the garden’s harvest was the apparent cause of annoyance for the ‘ELMO AZVI’ consortium, which by the way, doesn’t cure the population’s hunger for respect.

Provoked by the residents’ intervention, local managers got up from their splendid cribs and decreed the end of the garden. Heaps of stone and sand were quickly poured into the holes. Instead of the continuation of the work, the machinery covered the holes as if it were covering mouths. They hid the tracks with loose gravel, mixed with dust, exposing residents and passersby to a new range of risks and emotions such as nervous breakdown, breathing problems, sight problems, dry throats and slippages. As if that isn’t enough, they’ve announced this was all in vain, that the trams won’t even come here: there’ll be new routes. “The tram? It’ll only go to Vista Alegre! And the rest of the tracks already done…? So what. Leave it.”

Like the Olympic legacies, from our windows there’s no sight of the work that cost so much, nor the plants that at least grew. Welcome to the Alexandrino Street desert; from oasis to wilderness.

Maybe cacti are more appropriate to this environment. Instead of asphalt, sand; instead of trams, camels… Whether Santa Teresa residents or Tuaregs, life proceeds with struggle.

Maristela Grynberg is a resident of Santa Teresa, law student and human rights activist who studies social self-management and sustainability.