For the original article by Giula Afiune, Jessica Mota and Natalia Viana in Portuguese published by Agência Pública click here and scroll down to the final section.

The unsuspecting journalist who tries to enter the Minha Casa Minha Vida condominiums in the West Zone will quickly learn three things. The first is that they are all surrounded by gates that control the entry and exit of the residents. There aren’t any doormen. The second is that there are always a few strong young men leaning against the buildings or in cars, observing any movement. The third is that the residents are very afraid of giving interviews.

Reporters from Agência Publica learned of the reality of the fear imposed by the militia [vigilante cop mafia] during the two visits they made to the Colônia Juliano Moreira condominium in Jacarepaguá. The first time, a tall young man in a tank top called on us to explain what we were doing there. He did not introduce himself, but he nodded. Residents spoke of the militia in a veiled fashion, complaining that there was “not much freedom,” “children cannot be on the streets after 10pm,” or “there are too many people who want to boss everyone around here.” During the second visit, the surveillance was more ostentatious: while our reporter talked to a resident on the first floor, two young men watched from the ground floor, leaving the man and his wife deeply worried. “He’s not a militiaman, he is the son of a militiaman,” the resident said about one of the young men. Afraid, the couple didn’t want to give an interview or tell their story.

The fear of the power of the militia echoes another fear which is always constant in Rio’s favelas: the fear of drug traffickers. In the words of researcher Mariana Cavalcanti, “poor communities in Rio always have a boss,” and the control of entire buildings in the Minha Casa Minha Vida program by militias comprised of ex-policemen and firefighters is the great setback of this reality. According to the stories told, militiamen enforce order, charge taxes for gas, electricity and cable TV, give orders, and beat and expel residents who rebel against them. In this way they ensure their vision of “order” and “security,” keeping drug traffickers a long distance away.

The origins of the militias that currently control the West Zone of the city are the retired or off-duty corrupt police officers that took root in the West Zone under the pretext of fighting crime in the early 2000s. In September 2006, while he was a candidate for governor of the state, Mayor Eduardo Paes explained to RJTV, from the Globo network the efficiency of this type of militia: “You have areas where the State has completely lost sovereignty. We need to recover that sovereignty. I’ll give an example, since people are always asking about recovering that sovereignty. Jacarepaguá is a neighborhood where the so-called retired police force—comprised of policemen and firefighters—brought tranquility to the population. The São José Operário hill was one of the most violent in the state and now it is one of the calmest. [Also] the Sapê hill, over in Curicica. That is, with action, with intelligence, there is a way with which the State can return sovereignty to those areas,” he said. After the episode, Paes denied he had defended the actions of the militias several times.

A member of the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), Paes began his political career in that same region in 1993, as the sub-mayor of Barra and Jacarepaguá at 23 years of age. That is where he still maintains the majority of his electoral support—when he was re-elected in 2012, 822,000 of the 2,000,000 votes for him came from the West Zone. One of the areas where he had the highest percentage of votes was Santa Cruz, where many condominiums were built under the Minha Casa Minha Vida program. He obtained almost 77% of the valid votes there.

It’s not by chance that the presence of militias is much more prominent in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro. If the majority of the new Minha Casa Minha Vida projects are in this region, it is also not surprising that the vast majority of these buildings are controlled by them. According to government data, of the total of 16,309 people relocated through the program, half went to the [extreme] West Zone and the other half was divided among condominiums in central Rio, the North Zone and Jacarepaguá.

The mayor’s office also gave the numbers of families settled in some of the housing projects visited by Publica’s 100 project. Three of the most populated groups of condominiums—those in Campo Grande, Senador Camará and Cosmos, which together received 5,121 relocated families—are in the westernmost part of the city’s West Zone. These condominiums were inhabited by people who have already been through all the evictions processes described in the 100 report. There are reports in both about the presence of the militia.

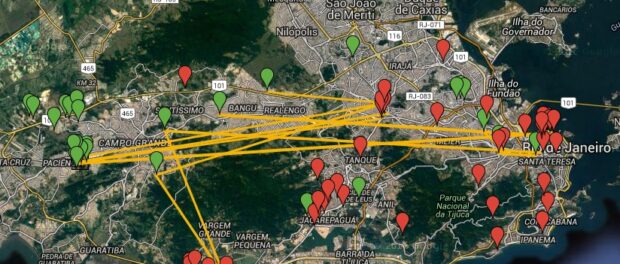

This map produced by Pública, with the origins and destinations of community removals linked to the Olympics, outlines the massive displacement and relocation that occurred in the West Zone. Pública used the locations of the Minha Casa Minha Vida condominiums built through the first half of 2015, investigated by journalists Luã Marinatto and Rafael Soares from the newspaper Jornal Extra, and information gathered in the dossier of the Popular Committee.

In a remarkable effort in reporting for the first half of 2015, the journalists from Jornal Extra found that, by that time, all 64 Minha Casa Minha Vida condominiums that had been launched in Rio for the poorest beneficiaries were targets of criminal groups. Over half—38 housing projects in the West Zone—were, at the time of analysis, controlled by militias. Among them are the Livorno, Trente and Varese condominiums in Cosmos, and the Treviso, Terno and Ferrara condominiums in Campo Grande, which all have some residents relocated because of the Olympics. In Cosmos, reporters caught sight of buildings that had the symbol—a black bat—of a famous militiaman, the ex-Military Policeman Ricardo Texeira da Cruz, “Batman,” above the phrase “Welcome.”

The absence of basic rights for the relocated residents—such as information about bills, the period of time for the property to legally become theirs and contract for delivery of the key—helps make them vulnerable to the militia’s demands. “The local sub-mayor’s office wields enormous power,” explains sociologist Paulo Magalhães, who observed the power dynamics in the region after being hired by the Invepar company to create a private social investment plan because of the construction of the TransOlímpica BRT. “And the articulated policy is made with two big markets—the security market and the formal real estate market.” Both interests, says Paulo, are linked. “The militia’s marketing pitch is to sell land where you won’t have security problems.”

It’s the new face of such an ancient habit that has permeated all phases of Rio de Janeiro’s history. Forced evictions happened in 1808 when the king of Portugal, Dom João VI, moved to Brazil and removed residents’ houses in the city center to install its luxurious court. The houses were marked with the abbreviation “PR” for “the Prince Regent,” a symbolic but real violence which resurfaced during the Olympic period removals: through 2013, all the houses to be demolished were marked with the acronym “SMH,” denoting the Municipal Housing Secretariat.

“The history of Rio de Janeiro is modeled upon construction and the expulsion of those who built,” reflects Sandra Maria, one of the inhabitants of Vila Autódromo who told her story for the 100 project. “Former slaves built the center of Rio de Janeiro and afterwards were expelled from it. Then they built the Santo Antônio hill and were expelled from it. The South Zone was built by workers expelled from Centro. The poor in Rio do not have the right to live near the privileged areas. They cannot live near the beach, they cannot live near the waterfalls, they cannot live near the forest. There comes a time when you ask: what is the value of the history of a people?” It was this perspective, she says, that made her decide to join the other residents in their fight and to stay there until she had her own little house in the small neighborhood which today borders the Olympic Park.

“Someone’s got to change the history of this city,” she says.