For the original article in Portuguese by Bianca Pedrina, Jéssica Moreira, Mayara Penina, Semayat Oliveira and Patrícia Silva published in Portal Aprendiz click here.

Often we hear phrases such as “she graduated, but not from USP (University of São Paulo),” or “she is excellent, but lives far away.” But time teaches us not to be embarrassed of being from the (São Paulo) periphery.

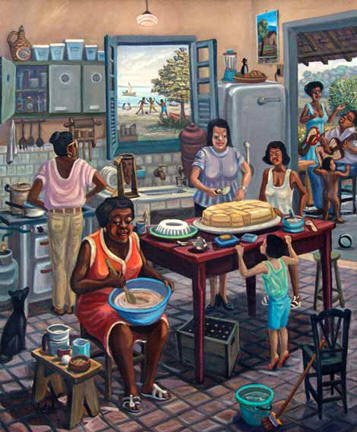

If the periphery had a gender, it certainly would be feminine. Like the heart of a mother, she hugs her children without distinction, whether they’re beautiful or ugly, within or outside of standards.

In the dictionary, the periphery is the region most removed from the center. The term designates only a geographic space, not the worst place in the city.

In São Paulo there are over 650,000 women living on the outskirts–and present in all the city, working, studying and going out with friends. In Brazil almost 22 million women are heads of households.

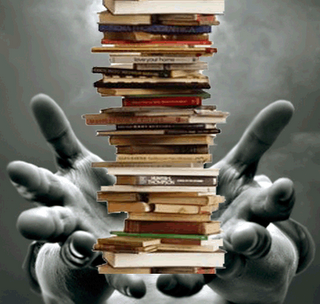

And for those considered faveladas (women from the favelas), reaching university is virtually impossible. It’s as if she was born with her destiny determined. She is never going to have enough money to pay for university and her public school will not prepare her.

But now, lovely, aggressive, full of self-confidence, these women are dribbling the difficulties of scaling the social ladder. They now include yet another activity which has turned their double life into a triple one, since they also study.

Today, more than ever, mothers that didn’t have educational opportunities can dream of studies for their children. In the periphery mothers show pride when they can say that their children have completed college.

Not that the diploma of higher education removes the sensation of being marginalized. “She graduated, but not from USP.” “She is an excellent professional, but lives far away.” That is the reality of many of the 3.6 million Brazilian women today in college.

The situation erases or hides diverse characteristics of the population that lives far from the grand centers. In the periphery there are, yes, people interested in art, residents engaged in social and political movements that want to show the plurality of this “other world.”

Yhorranna Ketterman, resident of Taipis, in the north zone of São Paulo, is an example. She became pregnant when she was 17 years old. They suggested she have an abortion, but she refused. At 28 years old and with two children Yohorranna dreams of a house, for she lives in an irregular housing situation. In the favela where she lives, the alleys are tight. If you open the door, you see attached homes–at least she can ask a neighbor to keep an eye on the children while she goes to work.

She is a metal worker and she separated from her husband after a fight that left her with a crooked finger. She was beaten, and also beat. As the strong woman she is, she decided to have the operation to not have more children, facing the machismo of her then partner, who did not want to have a vasectomy.

Alone and boss of the home, Yhorranna took control of her life.

It doesn’t end there, however. Who of us has never heard the famous declaration: “you don’t seem like you live in the periphery.” Well, as far as we know the women of the periphery don’t share a single standard of beauty, they don’t wear the same clothes and they don’t like only one type of music.

It doesn’t end there, however. Who of us has never heard the famous declaration: “you don’t seem like you live in the periphery.” Well, as far as we know the women of the periphery don’t share a single standard of beauty, they don’t wear the same clothes and they don’t like only one type of music.

We are black, white, young, old, mothers of other girls. We like photography, ballet, funk, theater. During a job interview, the location of our residence creates embarrassment. “Yes, I take the bus. Train. Two subways. And the bus again.” During the happy hour it’s common to hear: “Do cars go there? This time of day is dangerous. Want to sleep at my house?” The answer is no. We leave early and return late, but always return.

We work close, we work far, we drive cars, take buses. We are various women, with different stories, yet the same place. It’s impossible to reduce to a stereotype.

With time, the woman learns to explain that her neighborhood isn’t as dangerous as they say. She learns not to be embarassed to say that she is from the periphery, because that’s where her roots are and where she has learned all she knows.

To be a woman from the periphery is also to wait over a month to go to the gynecologist. It’s to not have access to daycare for your children. But none of this intimidates her. During this International Women’s Week, it’s worth remembering that the greatest poverty is not having space in which to be. In the periphery they do: they are women warriors.