Unreported in the local press, gang strife has returned to Rocinha. On the night of March 18th a shoot-out occurred between the remaining drug traffickers and Shock troops currently occupying Rocinha. The shoot-out left three traficantes dead, the community scared, and the press silent. Against the advice of residents I decided to spend the nights of the 20th and 21st in Rocinha. What follows is a description of the conflict, as I saw it unfold.

At 9:30pm on the 20th when crossing the white bridge from the Instituto de Reação into the community I found most shops closed, a majority of bars empty and police presence tripled.

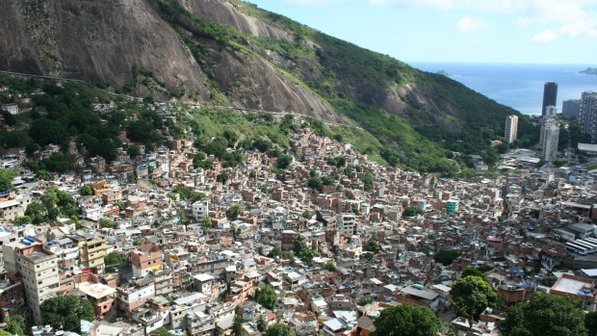

Rocinha is the biggest single favela in the Americas with an estimated population of 100-150,000. It was pacified last November 13th. At the time the community was ruled by the gang Amigos dos Amigos (ADA) led by Antônio Bonfim Lopes, also know as “Nem.”

Rocinha is the biggest single favela in the Americas with an estimated population of 100-150,000. It was pacified last November 13th. At the time the community was ruled by the gang Amigos dos Amigos (ADA) led by Antônio Bonfim Lopes, also know as “Nem.”

Before pacification through the State’s Pacifying Policy Units (UPP) program, Rocinha bore witness to several gang wars. It is located between two of the most lucrative drug markets in Rio de Janeiro, the South Zone and Barra da Tijuca.

During those conflicts gangs fought for control of the community. With pacification the nature of the conflict between gangs (and the police) has changed from an all out war to a cat-and-mouse game. Gangs are no longer fighting to gain complete control over Rocinha but instead are fighting “alley by alley” to control the different points of sale which have remained operating in the community after the pacification.

One of the main issues in Rocinha is the sheer size of the place, with its uncountable number of hiding spots and the tendency of the Shock troops to stay on paved roads.

When walking up the street the tension was palpable. In most houses the lights were off and the normal cacophony that greets you was absent. Upon arrival we decided to go to the bar around the corner to see what was going on. The bar happens to be next to Shock troops. On an average night there would be one car holding 4-6 police officers. This night there were four cars each holding 6 people, armed to the teeth.

When walking up the street the tension was palpable. In most houses the lights were off and the normal cacophony that greets you was absent. Upon arrival we decided to go to the bar around the corner to see what was going on. The bar happens to be next to Shock troops. On an average night there would be one car holding 4-6 police officers. This night there were four cars each holding 6 people, armed to the teeth.

At first they remain in and around the cars, but then a group of 8 officers with MD-2 assault rifles raise to shoot, then pass by us up into the beco, or alley. They stop several passersby putting them against the wall, and ordering them to pull up their shirts, amongst which is an 8 year-old boy.

The barman commented when I went to get another drink, “They can run up the becos all they like, those guys [the traficantes] know this place like their girlfriends’ behinds. It is futile the attempt these troops are making. It is only for the show of it.”

I spent the rest of the night watching “the show,” looking at the Shock troop cars passing up and down the street, and counting the reinforcement on motorbikes (30 in total) that was called in to control the situation. Not a single shot was fired up top the Estrada de Gávea, but residents in lower parts of the community mentioned they heard shots and grenades going off all night.

The next morning whilst walking through the community it seemed like everything had returned to normal, shops were open and children were walking hand-in-hand up the Estrada da Gávea to school.

As I walked down Rua Dois I talked to a local and asked him what the difference is between now and before pacification. He responds, “Before pacification we would also have tense nights like this, the only difference is there wouldn’t be any state involvement until the last minute. The state would only get involved in the conflict when somebody from the Zona Sul would get hurt or when things got really out of hand. Now that Rocinha is pacified they are present from the get-go and they have no choice but to intervene.”

The Shock troops are in the community and they are trained to deal with these types of situations, but they appear reluctant and scared: they park their cars in front of, and sometimes nearly inside, schools and projects for children; they drive around the community with the barrels of their guns pointing out the windows; and their apparent unwillingness to engage in any meaningful conversation with locals.

The increased violence by the different gangs involved in a turf war and the reluctant response of the State has left Rocinha’s inhabitants in a twilight zone. One resident told me: ‘The problem is nobody is quite sure who is in charge or what the rules are, so people are testing the limits. There are more robberies than ever and I feel much less comfortable letting my kids play outside by themselves.”

When I came back the next night there was no “playing outside” for anybody. I pass the Valão, one of the poorer neighborhoods in Rocinha. Normally at this time of night this one of the liveliest places in the community. There are people waiting to take a moto-taxi while enjoying a skewer from the street vendor. There are men and women having a beer in one of the pé-sujas and children playing on the street. But not tonight. Tonight the street is empty.

A friend’s friend tells me to go home as soon as possible “because there was a shoot-out in Roupa-Suja (one of Rocinha’s neighborhoods) and there are about twenty guys with guns walking around here.”

The bar I spent the night in last time was deserted and although the owner was there, he also told me to go home and stay off the streets: “Yesterday was a trial run, tonight will be cruel.” As I walked around I felt like I was breaking some invisible law, there is nobody else on the street, the light in the houses are off and nobody is playing music. I felt like an extreme jaywalker. Only there is nobody there to notice that I’m breaking the law that dictates I should have stayed home.

Once I get to a friend’s house I spend some time in the window and I see that although most homes have their lights off, several are lit. Most of these have young men with phones, walky-talkies and some with binoculars sitting in the window monitoring the streets.

When one of my friends decides to go for a smoke he gets stopped by five young guys and a girl. They are lookouts for the ADA and think that my friend is a lookout for the CV (Comando Vermelho, the rival gang). After he convinces them he is really just out for a smoke they let him return warning him to “stay of the streets.”

I spend most of the night at the window looking at the Shock cars and motorcycles racing up and down the street. Around 3am I spot the first BOPE (Special Forces Battalion) car and I know it is serious.

The next morning several residents told me there had been some tense fighting between the different factions, the Shock troops and the BOPE. One man told me he thinks that from here on “it will only get worse. This is just the beginning of it, if the State does not step things up they will return to the way they were.”

The State is stepping up, from this Friday onwards there will be an extra 130 officers assigned to Rocinha. But the problem is bigger than just one community.

Whilst things were heating up in Rocinha, on the other side of the South Zone in the pacified communities of Fallet and Fogueteiro, there were also skirmishes between traficantes and UPP police officers. The pacification is not yet able to live up to its promise of “bringing security” to the favelas.

It also shows that for the favelas to be truly pacified, and for the UPP to win over full cooperation of residents, a different modus operandi needs to be sought. As one resident explained, “The problem is there are still many people here that believe we were better off with the traficantes, because at least we knew what the rules were and we knew who was who. We don’t know these policemen walking through our streets and they make no effort to relate to us. I don’t trust them.”

If the police want a chance at succeeding it is vital that officers become more focused on communicating with the community. The government needs to gain the trust of the community, not by empty rhetoric and false discourse, but by listening to residents. They need to implement security measures in a way that will increase trust in the instead of alienating the community.