When following the news of political tumult coming out of Brasília this year, many international observers have likely found themselves struggling to wade through a sea of acronyms. This is because Brazil’s political system is characterized by a large number of political parties–35 in total, more than double the number of any other country–that are forced to form a constantly-changing maze of alliances and coalitions in order to govern.

In this article we aim to analyze how this extreme version of a multi-party system arose out of the Constitution of 1988, how it has impacted this year’s political unrest and what it means for the nation going forward.

How Brazil’s political parties emerged

Some prominent parties present in today’s government date back to before the constitution, such as the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), whose forebear, the (Brazilian Democratic Movement) MDB originally arose in 1965 to oppose the military dictatorship. Many more sprung out of differing ideologies, and others were formed based on regional criteria.

High levels of dissidence can be said to have contributed to the number of parties that emerged post-dictatorship, as politicians felt that the coalition-based federal system meant their party’s view was not being heard by those with greater numbers and more power.

Other parties have initially formed purely out of unique cases of political strategy: for example, the Republican Party for Social Order (PROS) was founded in 2010 by Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB) politicians Cid and Ciro Gomes so that they could protect Cid’s seat as governor of Ceará and avoid it going to Dilma supporter Eduardo Campos, of the PSB.

Still others were borne out of a primary ideological issue. The Green Party (PV) was established by environmentalists in 1986 in an attempt to promote environmental issues and policies related to sustainable development. In 2013, Marina Silva—former Senator from the state of Acre and Environment Minister under Lula as a member of the PT, and third place presidential contender in the past two federal elections (by the PV and PSB)—founded the Sustainability Network (REDE), another environmentally-focused party currently aligned with the PSB.

The nature of the coalition-based system often leads to political stagnation and inefficiency. Because the coalitions involve parties from across the aisle and are constantly forming and dissolving, they tend to lack the coherent ideological agenda necessary to make strong policy proposals. Likewise, individual members often switch parties or vote against their own party’s interests with little recourse.

Confusions and curiosities

If perennially evolving coalitions and ideologically wobbly individuals aren’t enough, confounding nomenclature can also be a significant impediment to keeping up with the goings-on in Brasília.

For instance, the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) holds what by global standards would be considered center-left views but the similarly-named Social Democrat Party (PSD) is center-right. The Progressive Party (PP) is in fact anything but progressive–rather a hotbed for conservative firebrands and anti-left nationalists like controversial congressman Jair Bolsonaro. In a twist of dark comedy almost too good to be true, the Party of the Brazilian Woman (PMB) stands firmly against abortion and 90% of its current representatives in Congress are men.

In name alone, four different parties mention the republic or republicanism, six mention democracy, and a whopping nine–from all sides of the political spectrum–reference either workers or labor.

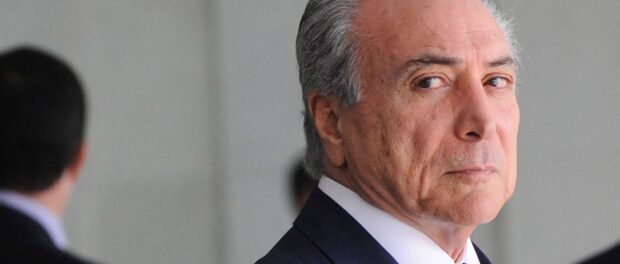

In light of all of this ideological flexibility, it should not come as too much of a surprise that the largest party of all–interim President Michel Temer’s Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB)–is widely acknowledged for not having any defined ideology at all.

The most influential parties in Brasília

PT: Perhaps the most influential party over the past two decades, Brazil’s Workers’ Party (PT) was born out of resistance and opposition to the military dictatorship and governed the country at the federal level from 2003 until last month under first Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula) and then Dilma Rousseff. As one of the largest-scale left-wing movements in Latin America, the PT holds a strong voter base in the North and Northeast regions as well as many major cities in the South and has been associated with social welfare policies which have significantly reduced inequality in the country.

PMDB: By official membership, the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) is the largest of Brazil’s 35 parties and holds the most seats in both the chamber of deputies and the senate. It emerged in 1979 as a party opposing the military dictatorship, but exists today without a cohesive ideology and now consists of members from vastly different ends of the political spectrum. In many recent elections, the party has not run its own presidential candidate, instead focusing on gaining ground in congressional races. Long an ally of the PT, the PMDB split from the ruling coalition in March in a move signifying their support for the impeachment proceedings against Dilma Rousseff. When Michel Temer officially took office on August 31, he became the first PMDB president since José Sarney, who held office from as Brazil transitioned to democracy from 1985 to 1990. Neither was elected democratically.

PSDB: While long seen as a direct rival to the PT, the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) actually developed out of a similar anti-dictatorship, leftist opposition movement in the mid-1980s. While democratic socialists at the time split to join the PT, social democrats founded the PSDB. That said, the party never affiliated itself with international social democratic institutions or trade unions, as social democratic parties elsewhere tend to do. It is today the third largest party in congress and held the presidency for eight years prior to the PT under sociologist scholar Fernando Henrique Cardoso from 1995 to 2003. Cardoso was associated both with the beginning of agrarian reform, human rights, and inequality reducing policies, and the deepening of privatization and sale of public capital. The party has since then taken a turn further to the right and is among those most convicted of corruption.

PP: Founded in 1995, Brazil’s Progressive Party (PP) is in reality one of its most conservative. Holding 47 seats in the chamber of deputies and six in the senate, it is the country’s fourth largest party. The PP embraces a neoliberal economic doctrine and certain factions support populist movements. Some of its most prominent members are highly controversial figures embattled by enduring corruption accusations, such as long-time São Paulo Governor Paulo Maluf and right-wing congressman Jair Bolsonaro. Despite all this, the party was aligned for years with Lula’s Worker’s Party on most non-economic issues but more recently split to support this year’s impeachment proceedings.

PDT: The Democratic Labor Party (PDT) was founded in June 1979 by Leonel Brizola–twice elected governor of Rio and associated with pro-favela policies–and members of the labor party descending from the Brazilian Workers’ Party (PTB) founded by Getúlio Vargas and outcast by the military coup of 1964. However, a legal maneuver by the dictatorship gave the group’s traditional initials to a different group of conservative politicians aligned to the dominating classes. The party has since begun a new chapter by adopting the initials PDT. The PDT was the first party of Dilma Rousseff prior to her joining the PT.

Recent events

Coalitions between parties are vital to Brazilian democracy: for any decisions to be made, the president must first seek approval from Congress, which houses representatives of almost all of the 35 parties. The most efficient way for the president to pass any new legislation is therefore for parties to form coalitions.

Lula granted the PMDB control over the ministries of communications, energy and mines, and social security in 2004 as part of the coalition agreements. However, upon reelection in 2006, Lula did not reintegrate these ministries, leaving the PMDB with only six ministries. Although smaller power struggles continued, the coalition between the PT and the PMDB remained civil until Dilma Rousseff’s reelection as president in 2014. Despite the PMDB announcing its support, 40.8% of PMDB representatives voted against reelecting her because they didn’t feel that her administration listened to them.

Struggles for power and representation have continued ever since, transforming growing animosity between the parties into a deep division. But the PMDB gained unprecedented representation in the form of Eduardo Cunha, Speaker of the House, the instigator of Rousseff’s impeachment. With Cunha leading the charge, the PMDB withdrew its support for the PT in March 2016. PSDB senators had already spoken about “working together” with the PMDB, and PP followed suit, announcing it was no longer aligned with PT in April 2016. Cunha, however, was expelled from office earlier this month amid corruption charges.

How influential are Brasília’s big party players in Rio’s 2016 mayoral elections?

Of the 11 candidates in the running for the coveted seat of mayor of Rio de Janeiro in the October 2, 2016 elections, the only major parties represented are the PMDB and PSDB. The position is currently held by PMDB’s Eduardo Paes, who has been mayor of Rio since 2009 following a political career that has included switches between PMDB, PSDB and the rightwing Liberal Front Party (PFL). Paes’ chosen successor is PMDB’s Pedro Paulo Teixeira Carvalho, and he’s been putting significant work into getting other parties and potential candidates to endorse Pedro Paulo as well. PSDB hopeful Carlos Osório who also worked in the Paes administration as Transport Secretary had also pledged allegiance to PMDB until February 2016, when he switched to PSDB in order to run for mayor. However, both are polling low in this year’s municipal elections, with Pedro Paulo at 6% and Osório at 4%.

The most popular candidate in the first round of the race for Rio’s mayor is Marcelo Crivella from the Brazilian Republican Party (PRB), a party that essentially exists as a base for bishops of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God to run for office. According to an Ibope poll released on September 23, Crivella holds 27% of the vote, which is 15% more than second most popular candidate Marcelo Freixo of the left-wing Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL), formed by members expelled from the PT and others who left by choice as the PT formed alliances with polemic right-wing politicians. The PSOL is the only party present in the Congress which does not receive money from large corporations and was the first to become a party through a massive signature campaign.

Since the 1980s, Rio’s leadership has been shuttled between the PMDB, PDT and PFL, with the exception of a brief stint with the Democrats Party (DEM), Brazil’s main right wing party, when César Maia switched from the PFL in 2007.

Looking forward

It does not seem that Brazil’s multi-party system will see significant consolidation anytime soon. To the contrary, an additional 12 parties from all ends of the political spectrum are currently awaiting recognition in the Superior Electoral Court. Notable among these is the Brazilian Favela Front Party (FFB), set up to launch favela candidates into political office.

With Temer and the PMDB ascending to presidential office despite never winning the vote of the electorate, the Brazilian people will likely not have the opportunity to make their voices heard until the next election in October 2018.