Theater of the Oppressed (TO) is an internationally celebrated participatory form of theater invented in Rio, in which there are no spectators, just spect-actors. TO was originally created by writer, director, and politician Augusto Boal in the 1960s, first in Brazil, and then further developed during his dictatorship-era exile in Europe.

“Brecht used to say that the spectator has to remain alert. I think that staying alert isn’t enough. The spectator has to say ‘stop!’ and enter the scene,” Boal said. One of TO’s most important techniques is “forum theater,” in which spect-actors reimagine the resolution of a scene by entering the scene and altering its course.

Theater of the Oppressed in Maré

Theater of the Oppressed began in Complexo da Maré in the 1990s. Currently, there are three groups in Maré. Marear began on the front porch of Janaína Salamandra, the Joker (facilitator) of the group. Her daughter, Carina Santos, gathered some high school classmates to do a TO workshop with her mother, and that experience kicked off the formation of the group. Soon after, the Center for Theater of the Oppressed (CTO) located in the Lapa area of downtown Rio, with sponsorship from Petrobrás, began the initiative “Theater of the Oppressed in Maré.”

Upon receiving funding, which went toward transport, snacks, props, and sets, the project formed two other groups: MaréMoTO and Maré 12. At present, there are 35 young people participating in these groups, with sixteen in Marear, the largest group. Participants range from ages 15 to 23. The sponsored initiative wrapped up at the beginning of 2015.

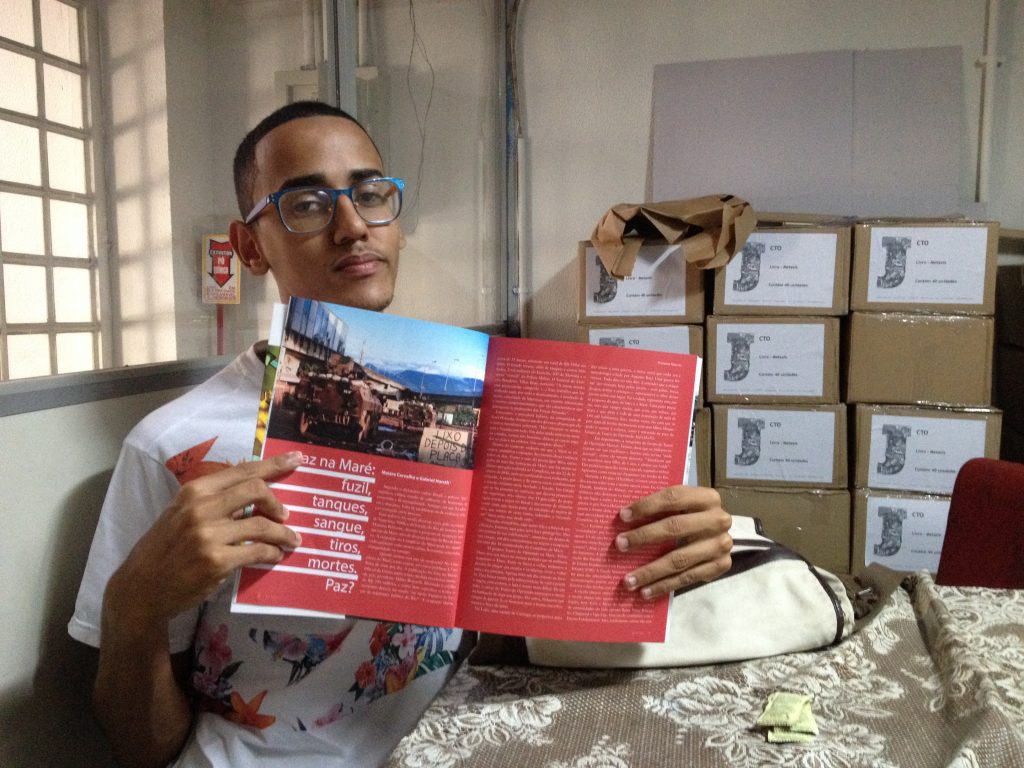

Gabriel Horsth, 19, of the Marear group, credits theater opportunities in Maré with his political formation. He started doing theater at age 13 through other community groups, and then began to do TO with Marear in 2011. Maiara Carvalho, 21, began TO just a couple of years ago, when a friend repeatedly invited her to participate. She initially insisted she was “too old,” at 18 at the time. However, when she attended her first TO performance, she found herself outraged in the audience, and resolved to enter the scene. This participation resulted in Maiara officially joining the Maré 12 group by the end of the afternoon.

Beyond their physical community, Gabriel, Maiara, and other “multipliers” from the CTO are involved in a budding TO initiative in the Rio de Janeiro Department of General Socio-Educational Action (DEGASE) youth correctional system for adolescents in conflict with the law.

Maré’s cultural landscape

Gabriel and Maiara are quick to point out that the TO groups are part of a unique cultural landscape throughout Maré in terms of theater, community journalism, and community research. There are around 100 social organizations in Maré, including Observatório de Favelas (Favela Observatory), Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré (Maré Development Networks), and Conexão G, the first LGBT organization in a favela. In addition to cultural groups and other social projects, Maré’s neighborhood associations are also strong.

Gabriel sees the totality of these groups as “where the resistance is [in Maré]. Over the years, we managed to construct a very cool story, but it lacks so much. However, it’s what makes it so that Maiara and I are here, young favela residents in this space. It’s what formed us. Many young favela residents don’t have this.”

Inspiring participation

Part of TO’s power in inspiring community participation is in the fact that it does not ask people to say what they think or feel, but to show it. As Maiara and Gabriel explain, forum theater seeks to avoid “characters.” Instead, it seeks to tap into sentiments and ideas its participants are not consciously aware of: “Everything is said in that which is not said.”

They stressed that the right moment for a spect-actor to enter a scene is after the main conflict has occurred: “People are already being killed and harassed. We have to focus on what we do afterwards, what the alternatives are.”

To warm up participants, TO uses games such as “the machine” or “siren’s song.” In “the machine,” participants will create a “machine”–for example of the favela or of the military occupation in the community–with each participant doing a repetitive motion or sound that they think would be part of the “gears” of such a setting or situation.

Afterwards, they come together to have a debate: Why that movement? Why that sound? What is behind it? Gabriel said the “machine” the Marear group made of police occupation was “hard, heavy, and raw… when we start to debate this, you begin to see how our body speaks of our realities.”

In the “siren’s song” game, participants close their eyes and think of a personal story of oppression and then make a sound they associate with that oppression. After all the participants have begun to make their sounds simultaneously, the group joins together similar sounds in four groups. Each group shares their stories of oppressions, and typically finds very similar stories are behind the similar sounds.

“My story could be the end of your story, or its beginning. Then, we know this group has a story to tell,” Maiara explained. At that point, that story will be done as forum theater, “not because they deserve to be told, but because they have an urgency to be told. My story is personal, but our story leaves the personal and moves into the social context.”

The State present in its absence

Gabriel and Maiara’s participation in TO in part stems from a conviction that Maré is a place deeply in need of alternatives. The expanded TO initiative in Maré started during the military occupation of Maré, which began prior to the 2014 World Cup in April 2014 and brought military forces into the community, including 1,180 Military Police officers (including BOPE special forces), 250 marines with assault rifles, 21 armored tanks and four helicopters. The occupation was set to last four months, but went on for 15 months. In the first 15 days of the occupation, 16 people were killed, and 160 arrested.

“The State is present in its absence,” Gabriel quotes Maré community journalist Gizele Martins with this sentiment, and explains how it was a turning point in his thinking. “I was always speaking out on wanting the State to be more present. But it is present. When it is present, it’s present in this way, with tanks.”

In the article that Gabriel and Maiara collectively wrote about the occupation for TO print publication Metaxis, they describe horrifying scenes, such as the experience of another Marear participant, Tailane: “[The military] asked me to wake up my son, who is one year old, and open his diaper,” supposedly to see if she was hiding things there.

This kind of practice was normalized during the occupation due to a sort of “collective warrant“ established during the occupation. Gabriel describes his own movement between parts of the favela impeded by police officers who harassed him and his friends, sometimes hurling homophobic insults at them. He explained that the TO in Maré initiative faced challenges for participants to get to rehearsals due to the tense environment.

While the stated objective of the occupation was to pave the way for Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), two years later, the community has still not received a UPP. In March, Rio de Janeiro Public Security Secretary, José Mariano Beltrame, said that the UPP would not be installed in Maré this year due to the state budget crisis.

Territory in Maré is disputed by three different drug factions and militias, and life has returned to pre-occupation norms. Confrontations between police and traffickers are common, as are police operations closing schools, daycare centers, hospitals, and businesses, and impeding the free movement of residents. The frequency and intensity of these operations increased dramatically in the months ahead of the Olympic Games and continued through the global event, sparking a community rights campaign in response.

Gabriel explains the current situation in Maré as “residue of dictatorship in these communities, which is heavy.” He says that he will “never stop fighting. But living in a place where I could die any day, where sometimes I don’t manage to go to work because of gunfire, and where stray bullets often pass through the wall, weighs us down.”

Gabriel’s family in particular has suffered from Mare’s day-to-day realities. Two of Gabriel’s brothers were killed related to trafficking, one killed in a police operation, and his youngest sister died as a result of medical negligence. Gabriel has written a play based on his mother’s story, and that of other women in Maré, called “Varnish: They Killed My Son,” for a woman who has buried five sons, insisting that all their coffins were painted with maroon varnish. The play won first place in a call for proposals by the Ministry of Culture. It will be performed in November in different private homes in Maré by Gabriel, Maiara, and three other participants from Marear, in an effort to deconstruct traditional theater.

Beyond the occupation and police operations, Gabriel and Maiara explain how they feel the structure of the favela “is made to go wrong,” taking schools as a particularly strong example, and echoing some of the sentiments of students occupying high schools earlier this year in Brazil’s “Student Spring.”

They describe how Mayor Eduardo Paes‘ administration announced plans to build new schools between Nova Holanda, terrain of the Red Command (CV) traffickers, and Baixa do Sapateiro, terrain of the Third Command (TC) traffickers. The school that exists there does not have class much of the year due to crossfire, and has bullet holes peppered throughout the doors.

“For the favela to not ‘come down from the hill’ [quoting the famous samba lyric] you need a structure that is well set up to go wrong,” Gabriel explains. Maiara qualifies this: “When we talk about ‘coming down from the hill,’ we don’t mean in a violent way. It’s people mobilizing, people speaking out, people protesting this system that is against this immense population of Rio de Janeiro that lives in favelas. We are always in the second plan, or not even in the plans, but the day that we’re in the first plan, a lot will change, in Brazil, in the world.”

Bottom-up lawmaking

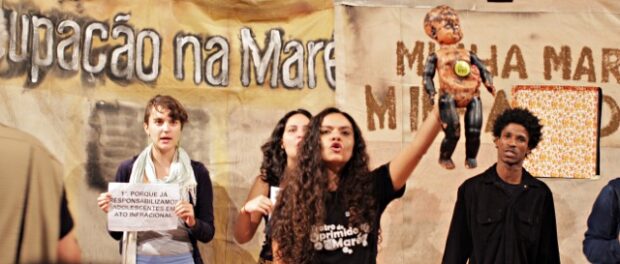

TO in Maré works directly to get favela public policy agendas “in the plans” through “legislative theater.” Legislative theater is a TO technique which employs the participatory forum theater, but in this case invites policymakers to participate with the goal of formulating concrete policy proposals.

Each of the TO groups in Maré has a thematic focus: Maré 12 has a focus on sexism; MaréMoTO has a focus on gender; and Marear has a focus on spatial discrimination against favela residents with respect to the labor market.

Last year, Marear did a forum theater piece inviting lawyers to participate and help the community understand what is legally possible to combat spatial discrimination, in which favela residents allege discrimination after they have revealed their addresses in hiring processes. After the scene, community members suggested proposals, lawyers reviewed feasibility, and three proposals were advanced to a community vote.

The winning proposal was to impose consequences not for the employee guilty of discriminating, but for the entire company, obligating the company to enter a “black list” for spatial discrimination. This would mean the company must donate money to social projects in the community, and that it be temporarily impeded from receiving certain government subsidies.

Gabriel said, “while I see politics in everything, [through legislative theater] was the first time I went to the State Legislative Assembly (Alerj). I had never participated so concretely in politics.”

Community reception to TO

TO in Maré has been welcomed with open arms by the community. Through forum theater, and its reimagined resolutions to commonplace situations of sexism and other forms of violence, Gabriel and Maiara hear community feedback that helps participants see new strategies for responding to situations in their own lives, and strategies they plan to use.

“The idea is to continue mobilizing. It’s not overnight, it’s a process. [TO] is a preparation for reality; it’s a wake-up call,” Gabriel explains.

This was particularly poignant in the case of legislative theater: “You see the community participating in the whole structure of public policy, the community being heard, and the law being advanced from that place.”

Moving forward

While the TO forum theater pieces take place in “the street, school, partner spaces, plazas, wherever we are invited,” the TO actors do need reliable spaces to both rehearse and to store props and sets. Gabriel and Maiara say this has been their biggest challenge of late, particularly since the initial Petrobrás funding to expand the project ended last year.

After the Petrobrás project was passed, the groups expanded geographically beyond Nova Holanda to the Piscinão de Ramos and Baixa do Sapateiro areas. They have rehearsed in spaces donated by community partners to date, with Maré 12 at the Americo Veloso community health clinic, Marear at the Observatório de Favelas, and MaréMoTO in the Museu da Maré community museum. However, there is no longer space for them in the health clinic, nor in the school they moved to temporarily afterwards, and the Maré community museum is facing eviction.

“As soon as we find a space, it’s not long before someone asks for it back. And we have too many things to store that we can’t lose. If we lost our sets, we wouldn’t have the resources right now to reconstruct them,” says Gabriel. Maiara adds: “For more young people to wake up, we need a space. Space for theater, sports, arts. Theater of the Oppressed has been a space of privilege for us. It’s surreal. We became political citizens.”

To donate to the Center for Theater of the Oppressed, Catalytic Communities, the US 501[c][3] nonprofit that runs RioOnWatch, can also act as fiscal sponsor for those who would like to make a US tax-deductible donation in English here. You may follow up at donate@catcomm.org confirming your donation is earmarked for “Theater of the Oppressed.”

In Brazil, donations can be made directly using the following account information: