Human rights are universal civil, political, social, economic, and cultural rights, indivisible and inalienable. This means, simply, that they are valid for all, that under no circumstances can some be respected and not others, and that no one can lose them, regardless of what they have done or will do.

The Brazilian Constitution guarantees equality “before the law, without any distinction whatsoever, guaranteeing Brazilians and foreigners residing in the country the inviolability of the right to life, to liberty, to equality, to security and to property” (Art. 5º). Furthermore, it guarantees that, “no one shall be submitted to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment” (Art. 5º, III) and that “no one shall undergo legal proceeding or sentencing save by the competent authority,” (Art. 5º, LIII) and assures that “prisoners are ensured of respect to their physical and moral integrity” (Art. 5º, XLIX), among others. Despite having a system of the strongest laws to protect these rights, in practice the state systematically violates them.

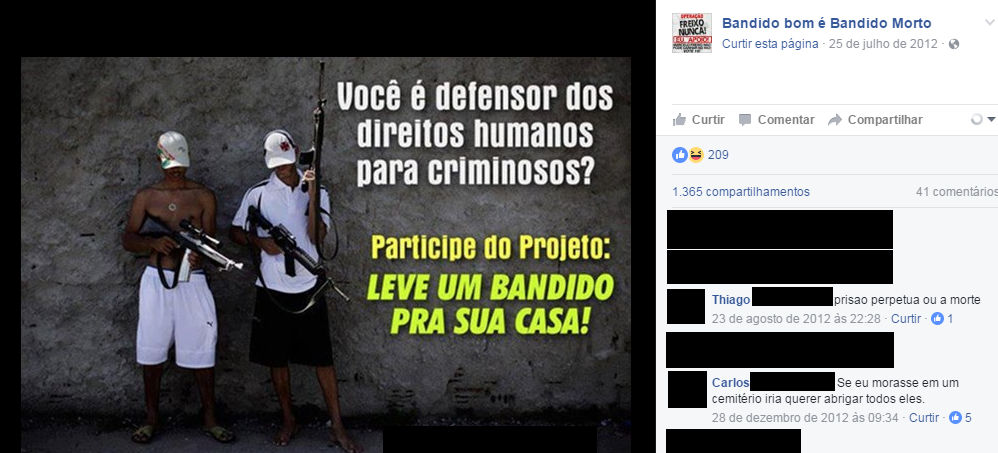

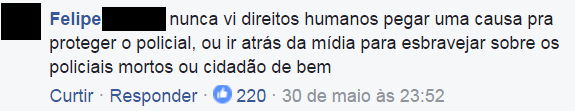

In addition to having a state that violates, Brazil has also witnessed a recent movement of a portion of the population towards rejecting the concept of human rights as the left’s banner to protect criminals. These usually stress the maxim of “human rights for the right humans,” as if rights were not universal, but attained through merit and good behavior. Many even like to rebut those who position themselves against human rights violations with the slogan, “if you feel sorry for them, take them home,” or in another variation, “adopt a thug.” At the extreme, some even suggest that, “a good bandit is a dead bandit” (“bandido bom é bandido morto“).

Outside of Brazil, in consolidated democracies, human rights are frequently seen as an essential base for progress, and of democracy itself, so that such misunderstandings are less common. Here, we deconstruct five common myths surrounding human rights in Brazil:

Myth 1: Human rights are for criminals

Human rights guarantee for those who are considered criminals, as well as for any person, rights such as the presumption of innocence, the right to a trial, and the right to physical integrity. They do not guarantee special treatment, unconditional liberty, or privileges. If the “human rights people,” as those who stand up for human rights in Brazil are often referred, intervene to guarantee the rights of a criminal, it is not because the criminal is right or deserves more but because he or she is in a position of vulnerability in which they seek to ensure their rights guaranteed by law.

Those who reject human rights are not advocating due punishment for crime, but rather for retribution in the same way. And if we reciprocate in the same way, what differentiates us from a criminal? As if violence could be a means to create order? And as if we could convict a criminal by breaking our own law? To oppose human rights is to oppose the law; violating human rights is to violate the law.

When we treat the rights of a specific citizen as relative to their situation, we are weakening the institution itself and opening the precendent for this right to be disrespected again in the future, including with any of us. It is necessary to overcome the supposed opposition between the police and human rights, and the view that rights are an obstacle to justice and combating crime. The police have a duty to protect citizens—and this protection cannot be selective, nor can it be only negative, in the form of protection against violence, but it should be positive, in the way of promoting rights.

If this protection could actually be selective, who would define who should be protected and who shouldn’t? Who can define which gangster should have his or her rights violated and which shouldn’t? How can we let institutions like the police which are founded on prejudices that victimize poor, black youth more than anyone else define who is a “good citizen?” And what of the limit of illegality that separates a “good citizen” from a criminal?

We cannot work from the principle that there is an essentially good side and another that is essentially bad. That some crimes are more acceptable than others. That the “good citizens” merit more because they work, they pay taxes, and they get up early. It is only fit for the courts to judge their crimes with a basis in a constitution that guarantees equality before the law and universal human rights.

Due to its great importance, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, established by the UN in 1948, influenced the majority of constitutions of countries in the world created after its publication, and it is the most translated document in the world.

Myth 2: Those who defend human rights are in favor of not arresting criminals

They are in favor, yes, of fair treatment for criminals, of prisons that are not overcrowded, and of prohibiting practices of torture. They are in favor of structural change in education and in opportunities so that fewer people resort to crime, and in favor of rehabilitation for the offender after serving his sentence to be reintegrated in society and have opportunities so as to not fall back into a life of crime, creating a safer environment for all. Justice cannot be synonymous with revenge.

Myth 3: That there are “human rights people”

Some in Brazil have the habit of calling those who go to prisons to offer legal help and classes to prisoners, or friends who prevent others from “teaching a lesson” to a thief caught in the act as “human rights people.” To say that “human rights people” exist is to imply that all others are not, that they are not interested in human rights for individuals.

In reality, the “human rights people” are just trying to ensure equal access to the rights provided in the constitution for you and all of us. He or she is not trying to release a criminal, just trying to make sure that he or she will not be tortured or beaten, but tried and arrested as any other citizen holder of rights would be.

Myth 4: “Human rights” are a leftist motto

It was not the left, and certainly not the Brazilian left, that invented “human rights” or decided that they would be inalienable.

Human rights in their current conception were codified in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. In the context of their creation, they refer to the violations committed in the context of the World Wars, including the use of the atomic bombs and the Holocaust, and also to the context of the emergency of the Cold War, which set capitalists and communists in opposition. This is reflected in the incorporation, for example, of the rights of the citizen to property and of the right to not be arbitrarily deprived of it, among many others.

The Declaration is not binding, so it does not need to be ratified and it does not provide for penalties against those who violate it, but all 196 UN member-states signaled their acceptance when they entered the organization. Of the nine major international treaties that codify the principles contained in the Declaration, all UN member-states have ratified at least one.

Numerous countries whose governments are center-right have human rights as important values. A symbolic example is Germany, in which human rights are a key element in constructing national identity due to the traumatic mass violations during the Nazi regime, and more recently reflected in the decision to welcome the large influx of refugees.

Myth 5: There are no human rights for police and for the families of victims

Human rights are universal, that is, they are for all, and inalienable, that is, no one can lose them. Police, their families, and the families of victims of acts of violence are as deserving of rights as any other person, but not more than another person.

Brazil has one of the police forces that most kills and most dies in the world. In Rio de Janeiro, the State Legislative Assembly’s Human Rights Commission meets with families of killed police officers to provide both legal and psychological support, just as with the families of any victim of violence.

The police need to understand that there is no opposition between police and human rights, but that human rights exist to protect the police as well. This includes not only the right to physical integrity, often threatened in their profession, but also to combat degrading and humiliating treatment within the police institution itself.

Human rights are not only for right humans: they are for everyone.