Edward Saïd’s theory of Orientalism offers a useful reference for considering the attitudes of wealthy Brazilians towards favela residents, as well as perhaps the perceptions of non-Brazilians towards Brazilians in general. Saïd states that the West has historically created a specific image of the Orient—the East and particularly the Midde East—that legitimizes imperialism. It is an essentializing dual image which exoticizes and romanticizes Eastern culture by stressing its rich mysterious traditions, sensual women and passionate characters, while on the other hand ridiculing Eastern peoples and their abilities by depicting them as irrational, violent, forever stuck in the past, and thus underdeveloped. He argues that the resulting conclusion that comes from emphasizing how different people from the Orient are, is that the West is rational, better and superior. An accompanying conclusion is that the West has to take the East by the hand, and rule over or help its people, because they cannot do so for themselves.

Similar patterns are at play in the common perception of Rio’s favelas. In interviews with residents of gated communities in Barra da Tijuca, the two sides of this story were apparent.

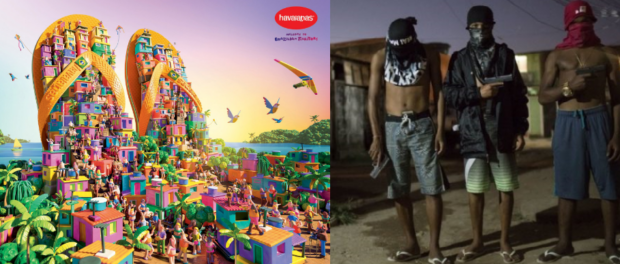

On the one hand, interviewees described favelados, favela residents, as people who live their lives passionately and produce popular culture. André, for example, lives in the Península condominium and thinks that favela residents “live their life more than we do.” They are exoticized in advertisements as happy people in colorful homes. Rio’s best known handicraft market in Ipanema and tourist shops across the city sell paintings and sculptures of favelas, and favela tours often profit from tourists regarding those spaces as home to an Other (although community-led tours can debunk notions that favela residents are different from anyone else).

On the other hand, condominium interviewees presented an image of the favela as a space of crime, where residents always resort to violence and are never able to help themselves without order being bestowed upon them from the outside. This notion is often reinforced through television programs that show police doing drug busts or “pacifying” criminals in favelas and media outlets that publish selective, sensationalized articles about violence in favelas.

Marcelo has lived in a gated community all his life and explains that he “always hear(s) two stories: either ‘traffickers and violence,’ or ‘good people always trying to find a smile.’” Amanda, an architect who just moved to a gated condominium in order to raise her children without worrying about their security, argues that welfare policies have kept favela residents dependent: ”The poor are dependent on the Workers Party (PT) that gives the people money. It goes directly into their hands, instead of to education and health.” This argument suggests doubt about favela residents’ abilities to spend their money wisely and presumes they are not active contributors to society.

Then again, other gated community residents were more empathetic in their definitions of favela residents. Flavio from Barra says people from favelas are ”just people born in another place.” He added that “traffickers and criminals are the minority, the majority is good.”

Broader society often views Rio’s thousand diverse favelas as uniform neighborhoods. Carlos Alberta Costa, commonly called Bezerra, is president of the Asa Branca Neighborhood Association, leading the relatively small and peaceful favela in the West Zone. He complains that police treat Asa Branca residents as criminals anyway: ”The police come into this area with the idea of a favela as extremely dangerous. They use violence against our residents, who are not criminals.”

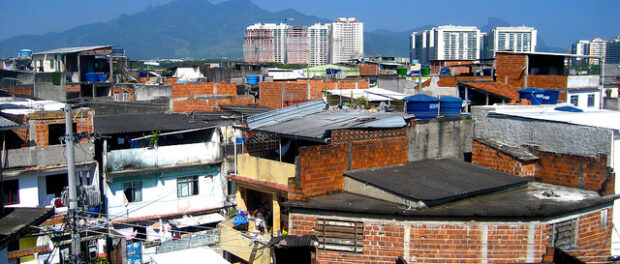

Rather than assumptions about cultural differences or violence-related stigma, Xaganthe, a resident of Rocinha in the South Zone, prefers to draw the line dividing favela residents from others around the historical circumstances and subsequent empirical differences of their communities: ”The difference with the asphalt (formal city) is huge. They (in the formal city) have more options. This difference comes from the time slavery was abolished. Black people lived in the hills (which were public land, and thus easier to occupy). So, black and poor people were not valued and didn’t receive support from the government. No basic sanitation, paved roads. Policies and the government didn’t go there.” In his view, history has shaped the favela and the formal city differently and these environments in turn shape the life experiences of people living in them.

Caesar, 50, also lives in Rocinha and is proud when speaking about the community, but discloses the complexity of identifying his community as a favela: ”The word favela is very limited and has some negative connotations that don’t tell the story of every community. But, on the other hand I’m very proud to be a favelado.” Talking about favela tourism, he says: “It’s good that many people want to see the soul of the favela.” So while he doesn’t like to be stereotyped by outsiders, Caesar sees value in being part of a community and shared culture with which he can identify.

Legitimizing violence against the “Other”

“Othering” favela residents, or essentializing them as fundamentally different people, makes it easier for non-favela residents to dismiss or even participate in exclusionary policies, such as relentless police violence, bred on the “othering” of these neighborhoods. If the incidents of violence in favelas can be perceived to be attributed to something inherent about favelas or their residents, non-favela residents feel absolved of responsibility and even legitimized in their prejudice. Under such circumstances, they do not consider other factors at play, their role in the process, or the historic conditions they may not have been responsible for, yet which ultimately led to the current reality which benefited them at the expense of others.

Central here is the theory of structural violence. Sociologist Johan Galtung separates this from “personal” or “direct” (physical) violence. It concerns less incidental and observable acts and is performed indirectly. The uneven distribution of resources, for example, aren’t a short-term aberration, but an integral part of society that can be considered violence through exclusion.

The everyday fact of lower life expectancy for the poor doesn’t make headlines as easily as an incidental triple homicide, for example. Pedro, living in the Rio II condo, believes that “‘human rights’ exist only for the criminals. The media shows them murdering so many people, but still they always ‘deserve a second chance.’ Last week I saw that a mother was killed in front of her daughter. That child doesn’t get a second chance.”

The effects of structural violence appear less shocking because they don’t stand out from daily life, which explains the common tendency, including among the media, to focus on the ‘single story’ that depicts problems concerning spectacular physical violence, instead of more systemic problems.

Vinicius from the Via Barra condominium notices a tendency of Barra residents to distance themselves from the rest: ”At some point in the 1980s people in Barra actually tried to separate themselves from Rio. This is the kind of thinking of ‘we are better because we are rich.”’ Wanting to separate the “developed city” from the rest of “troubled Rio”–although many favela residents enter Barra’s gated communities everyday to work–is a kind of exclusionary violence that is closely, but rarely, connected to the physical, headline-grabbing violence.

Those living in the formal city and those from favelas are not different breeds of people, living within their own separate ecosystems of violence. Distorted images on the television of ever-dangerous favelas, or careless and joyful favelados, only further consolidate the vision of favela residents as the “Other.” Favela violence is a tangible, easy-to-sell problem of the “Other”; the real problems—structural violence and its sidekick, stigmatization—have not been given their due attention and unfortunately are thus much too easy to overlook.

Christian Kuitert is pursuing a Masters degree in ‘Conflict, Territories and Identity’ at Radboud University, Netherlands, focusing on comparative citizenship in Rio’s favelas and condominium communities.