For the original article by Saulo Pereira Guitarães and Bibiana Maia in Portuguese published in Vozerio click here.

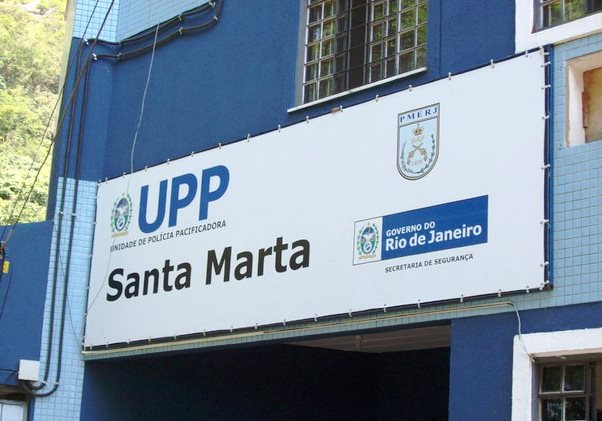

The first Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) was launched at the end of 2008, in Santa Marta, in Rio’s South Zone. Eight years later, Vozerio spoke with favela residents that went through the experience to gather impressions, opinions and expectations in relation to the program.

What will be the future of the UPPs? In the midst of the state’s financial crisis, this is one of the questions intriguing residents of Rio. The program, which turned 8 last month, allowed for the retaking of territories by security forces and the reduction of armed confrontations. It was also fundamental for the reduction in the rate of homicides in a state that, in 2012, reached a rate below the national average for the first time in 32 years.

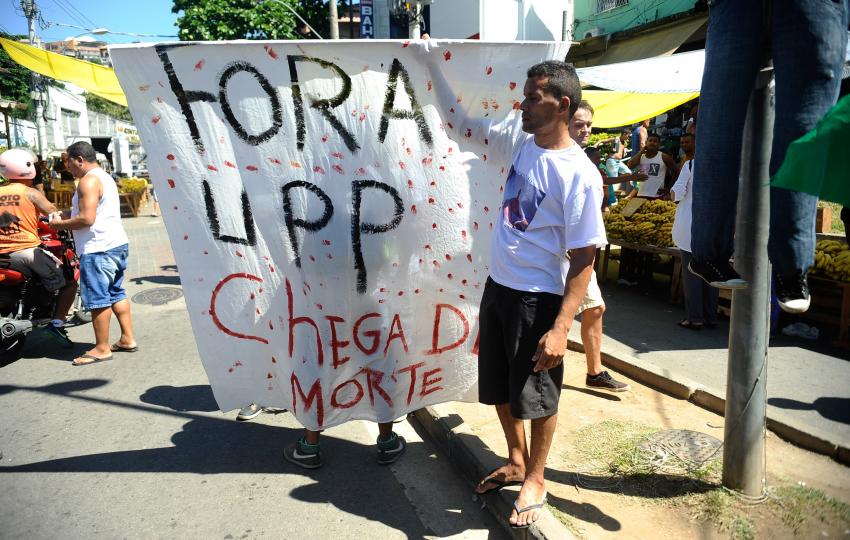

However, changes in the original format, the absence of critical evaluation mechanisms and cases like that of brickmason Amarildo (Rocinha, 2013) and the young Eduardo (Alemão, April 2015) are seen by experts as serious flaws in the initiative. In 2016, many UPP areas suffered from armed conflicts. Vozerio spoke with residents from occupied favelas and the majority appeared pessimistic in relation to the program’s future. See some declarations below.

“ONLY THE POLICE REMAINED”

“Insecurity isolated Morro dos Prazeres from the rest of Rio before the UPP. Very violent police operations were common. I remember well the education and politeness of the Military Police at the launch on February 25, 2011. From the start, the main positive aspects were the possibility to denounce police excesses and dialogue with the rest of the city. We had seven years to articulate and obtain improvements in health, education and other areas through contact with school directors, business owners and other people. The negative point was the incapacity of the government to take things forward. Only the police remained. When Amarildo’s story came, the inability of the State to respond shocked me. As a fan, I didn’t have any more arguments for those that told me everything remained the same. The idea of community policing fell flat. If we didn’t have political desire with money, without it we weren’t going to have anything. I don’t think that the project will end, but I believe that it will be left to its own fate. – Charles Siqueira, community activist and resident of Morro dos Prazeres, occupied since February 25,2011

“EVERYTHING WENT BACK TO BEING ABNORMAL”

“Before the UPP, violence was the result of the abandonment of the favela by the State. In 2009, police actions intensified and weakened drug trafficking. When they created the UPP, the Special Forces Battalion (BOPE) entered without firing a shot. A positive point in the first three years was the decrease in confrontations. There was a good exchange between residents and the police. The first teams didn’t have certain vices. But we always demanded long-term policies. And the actions here lasted, at most, two years. The neighborhood policing was undone by the change in Military Police officers. Everything went back to being abnormal. In 2013, we protested against the curfew and other measures. This was before Amarildo, which was an extreme case. Our mobilization was so things wouldn’t reach that level here. Since then, I think that if one doesn’t think about health, education and other areas, everything will end up like that or worse. The end of the UPPs wouldn’t be a shock or a surprise. But it would be sad to know that the State gave up on everything once and for all, even with regard to a policy that is questionable.” — Kennedy Lemos, social educator and resident of the Morro do Borel, occupied since June 7, 2010

“THE UPP IS STILL YOUNG”

“Santa Marta was like any favela, with shootouts and police action. After the occupation, safety increased. With it, more tourists came, new NGOs and government entities. But there was a problem too. No one was prepared for the UPP. There was abuse of authority, resistance by residents and other conflicts. It’s not from one day to the next that you transform an 80-year old community. At this time, the UPP is still young. There is still a lot of distrust, due to previous police corruption. Change requires time and patience. Receiving tourists is good, but it generates discomfort too. Aside from visitors, we want the end of open sewers and of electricity and water outages. If this doesn’t happen on São Clemente (the main road at the bottom of Santa Marta), why does it happen here, if today we also pay taxes? I hope there is more order, progress and respect not just in the favela, but everywhere. We have to demand this from the government. The State has to review its practices, to research more, to dialogue better.” — Valdeci Pereira, pastor and resident of Santa Marta, which has a UPP since December 19, 2008

“THERE WERE LESS EXCHANGES OF GUNFIRE”

“The population in Alemão lived with a parallel power in control, but it was different than what we live through today. There was violence, because there was a parallel power and police attacks, but there were less exchanges of gunfire. Then came that cinematographic occupation with violence. With the exit of the army, and the entrance of the police, it started to destabilize. The first police officers were trained for the UPP, then came those from the Special Forces Battalion and from the Military Police. In Alemão, the way that the police came in would never bring a solution. They came in violently, but not with policies. Today I live in a territory occupied by two factions: drug traffickers and the police. The UPP became an old-school police post, with a professional that doesn’t stick his head outside the cabin, at risk 24 hours a day. They aren’t seen as normal people, but as monsters by the community. They kill to defend themselves, end up shooting kids, causing fear and hate. Where UPPs should be is on the edges, to hold back the entrance of guns. A young person from here sometimes doesn’t know how to walk to the mall, how does he have a rifle?” — Lucia Cabral, from Educap, resident of Complexo do Alemão, with a UPP since May 30, 2012

“IF IT WERE SUCCESSFUL IT WOULD BE SO NOW”

“It’s clear that the UPP didn’t seek to bring tranquility to working class neighborhoods. There is an obvious relationship with the Olympics and the World Cup. It was the route for athletes and people that would come to the Games. Conflict exploded after the Olympics. It’s evident that it wasn’t planned for those that live in the city. It’s a dressing up of these territories. City of God was a favela with conflicts, dominated by drug traffickers. There were early morning shootouts. Immediately after the UPP there was an improvement, with public and private investment, but if it were successful it would be so now, and there would be no war. To think about City of God we have to think about the future of the city. The neighborhood is known as much worldwide as Copacabana, but it’s a popular neighborhood, and suffers socio-economic difficulties. We have to think about public safety without anger towards poor neighborhoods. People affected by these spaces have to be invited to contemplate them. While there are people from the South Zone thinking about public safety in the favelas, it will never be enough.” — Vivi Salles is a sociologist and resident of City of God, which has had a UPP installed since February 16, 2009