From November 23-26, Rio de Janeiro’s State University (UERJ) and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s National Museum (UFRJ) hosted the II UrbFavelas Seminar, an event organized jointly by departments from several universities, governmental entities and civil society organizations. The event had more than 500 accredited participants taking part in the debate tables, presentations, photography and film exhibitions, and visits to community initiatives in favelas distributed across the four regions of the city.

The objective of the seminar was to debate upgrading initiatives in Brazil’s favelas, their advances and challenges, resulting not just in an intense exchange of case studies, but also in the proposal of concrete paths and alternatives to current public policies. Thus, it sought to offer to an audience of researchers, technicians and executors of urban planning policies a vision of the many actors and perspectives involved in these initiatives, especially thanks to exchanges with residents and representatives of social movements. The seminar aimed to discuss the favela not as part of the housing problem, but as part of its solution.

Architect and former rapporteur to the UN on adequate housing, Raquel Rolnik said in the opening conference that in 150 years of urbanistic practices, the intervention of the liberal state in the sense of organizing territory has been based on the logic of promoting individual property. The favela challenges this conception when appropriating public space and removing the materials borders of property, as well as those symbolic borders of individualism. In the favela, one’s house does not end where the other begins. “There, the street is the space of the essence of sociability”, illustrates Alan Brum, a sociologist and resident of Complexo do Alemão, also director of the Instituto Raízes em Movimento. This type of sociability is described by Edith Medeiros, an architecture student and resident of Complexo da Maré, as being able “to look next to you and find someone that helps, different from out there (outside of the favela). In the favela we don’t want to press ahead alone, we want to take our people with us.”

Favela upgrading programs, such as the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC), Morar Carioca and Favela-Bairro were discussed, and their advances brought to light, aside from their contradictions and setbacks. Fransérgio Goulart, from the Manguinhos Social Forum, questioned the repetitive mantra of land titling as a way to guarantee access to citizenship. “Regularization (of title) is going to mean more costs for the resident, because the price of land is going to go up, it’s going to be the end of electricity siphoning.” This may prevent a resident from remaining in their home. “Is it worth it for the resident to have access to citizenship on these terms?” he provoked. In the opinion of the event organizers and signatories, upgrading should go beyond the execution of construction works, advancing to the universalization of access to works and public services.

The event was based on the premise of the existing diversity among Brazilian favelas, in terms of shape as well as socio-economically and culturally. The organization of the event affirms that the favela is part of of the history and the development of cities, not an anomaly to be removed, and that, because of this, the same treatment given to other parts of the city should be dispensed to favelas. This question was taken up constantly during the debates. Fransérgio proposed a reversal of the “favela is (part of the) city” jargon, proclaimed during the event with the intention of highlighting the need for integration of the favela with the city at large, to the “city is (a) favela”, since it is favela residents who are largely responsible for the production and reproduction of the city.

This equal treatment doesn’t just reaffirm favela residents’ right to the city, but the acknowledgement of the material and symbolic wealth they create for the entire city. “Be careful to not reproduce a failed model of urban planning that treats the favela resident as an object of study and not as vibrant and thinking human beings”, alerted Sandra Maria, an activist and resident of Vila Autódromo, alluding to the symbolic wealth that comes from the creative potential of residents, beyond the material wealth they produce with their labor.

This failed model is supported in what Alan identified as the precariousness of public data on favelas, which complicates analysis of their problems and causes distortions. “IBGE (Brazil’s statistical bureau responsible for the census) says that 100% of the residents of Alemão have access to sanitation. But it doesn’t say that in many cases it’s in the form of open-air channels. But since official data say 100% of homes have it, they don’t invest in more public sanitation policies there.”

Sandra illustrated residents’ creative potential precisely in the actions they take when faced with a vacuum of public investment, also citing the challenge of sanitation: “In Vila Autódromo we built solutions to our problems. Upgrading was done by us before (the City) evicted us. In partnership with (health research institution) Fiocruz, we did an experimental project of green septic tanks to solve our sanitation problem, but it was destroyed with the removal of the community. The eviction didn’t just remove the resident, but the geography of the place.”

Sandra even condemned, emphatically: “To the question of if there’s room for a favela in the ideal city, I respond: the favela is a part of the history of this country. To deny the favela is to deny our history, the history of an enslaved people. It is to strengthen the eviction policies. They like to justify evictions on the basis of land invasion on the part of the resident. But if we are going to talk about invasion, we have to go back to 1500, when the Portuguese arrived here with immense ships, powerful weapons, and they enslaved, invaded the land, planted the flag and told themselves they were owners of it. Until today indigenous people die every day fighting for the right to live on land that belongs to them. The slaves, after abolition, thrown out onto the country’s streets, occupied the abandoned corners of the city. They built this city. And each time that that territory built by them becomes valuable, they are immediately removed from there, as if they were a disease, a wound.”

Several members of academia and favela residents spoke out against the use of the terms “sub-normal agglomerations” and “precarious settlements,” as used by IBGE, according to a conception that this language isn’t neutral, and instead has the potential to affect practices and policies. In a similar way, Sandra spoke out against the use of the term “slum” as an English-language translation for favela: “Slum presupposes that it’s a recent, needy community, without a defined structure. Favelas are, in general, established communities, that sought solutions to their problems. This needs to be understood mainly by those that study favelas, so there won’t be a distortion of reality.”

Sandra said that she became aware of this linguistic difference with the launch of the report Favelas in the Media: How the Arrival of the Global Press in the Era of Mega-events Transformed the Image of the Favelas, launched by the NGO Catalytic Communities during the seminar. The report analyzed, among other things, the evolution of media coverage of favelas by the international press, including the change of terms used to make references to favelas, the actors interviewed and the values associated with residents and these spaces. The report will be launched in Portuguese at Casa Pública in Rio de Janeiro on December 15, with the participation of Sandra and other guests.

Rafael Soares Gonçalves, lawyer, historian and professor of Social Work at Rio’s Pontifical Catholic University (PUC), echoed these concerns during his talk when demonstrating how a favela is built as an intermediate space, both apart from and a part of the city at the same time, and a space of absence, due to being defined by a lack of that which the rest of the city enjoys. He also put forward the necessity of challenging the conception of the favela as a space of marginality, as a place of casual accommodation for the urban migrant, as a receptacle of all the city’s problems. These conceptions, according to him, make it possible for the favela to be built as a reality to be overcome, even in more progressive models of public policy.

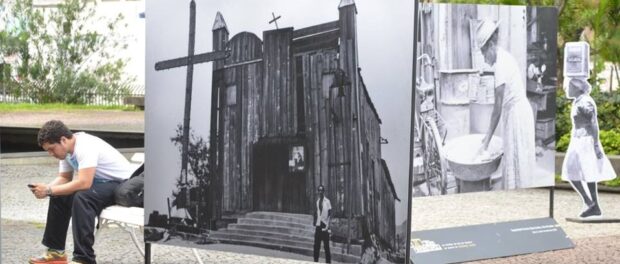

Rafael argued that it is necessary to think of them as permanent spaces. To think about them in such a way means thinking about them in historical terms, which he says has only happened in the last decade. This historicity is recovered through policies recognizing memory, that have a strong example in Vila Autódromo’s Evictions Museum, and in the resignification of the term favela, as has been done recently by a growing movement of residents that are proud to call themselves favelados.

The event acknowledged the fundamental importance of the protagonism of the favela resident, proposing that solutions be thought through together with the population and recognizing individual and collective initiatives by residents towards upgrading, seeing them as agents and not clients of public upgrading policies. In spite of having this objective, the audience reported the representation of favela residents at the event was low. “How many favelados participated in the event? How many tables included the presence of a favelado? The presence of a favelado at an event like this represents living history. I saw that the event registration depended on a title: graduate, masters, doctoral student. Where was the registration for the favelado?”, inquired Sandra.

The low number of favela residents wasn’t the only problem raised, but also that of language. “You all aren’t only speaking to architects, but to favelados as well. I am a favelada and you all are talking to me too. In my position in academia, as a Social Work Masters student, I learned a lot. It was a very good space for exchange, I learned a lot. As a favelada, I see that there is still a lot to be done to bring favelados here. I felt obliged to express myself at all the events I attended. If no one is here, someone has to speak and I spoke for us”, said Andreia Nogueira, a student of Social Work and resident of Cantagalo.

Edith agreed: “I have an academic side to me, because I’m an architect. But I have an even stronger side to me that is from the favela. If we want to talk about the favela, we have to bring a little bit of the language of the favelado as well. To abandon this academic discourse. The favelado knows what they’re talking about. This debate is important, it’s important to have Masters and Doctoral students here. But we want to be doctors, too”.

Despite concerns over this low participation, several favela residents recognized the usefulness of the debate during the entire event. “We took each other out of our comfort zones. When we agree, we don’t grow. And it was good that it removed a lot of things stuck in our throat”, said Luiz Claudio, professor of physical education and resident of Vila Autódromo.

The Open Letter from the Second National Seminar on Favela Upgrading, a synthesis of conclusions by participants and approved by the audience on the last day of the event, condemns the setbacks in the upgrading of favelas, in land regularization and in the provision of social interest housing. Among its proposals is the end of favela eviction policies, frequently based on arguments of ‘risk’ diagnosed as unfounded by engineer geologist Maurício Campos dos Santos during his presentation at the event. The letter also supports the increase of resources destined to social interest housing, the articulation of land regularization policies and technical assistance for housing improvements, and the occupation of empty urban spaces as a way of fulfilling the social function of property and as an alternative to peripheralization. The letter also includes an integrated agenda of public policies (education, health, culture, environment and leisure) to overcome social and territorial inequalities, the active participation of favela residents in the formulation and application of upgrading policies and a non-discriminatory upgrading policy which aims to overcome inequalities and guarantee full rights.

At the event’s closing, four motions were presented to be included in the letter, readily accepted by those present. The first demanded teaching related to social interest housing in architecture colleges, recognizing their central role in urban practice. The second was a motion against the closing of the ITERJ (Institute of Land and Cartography of the State of Rio de Janeiro, the agency that regularizes land rights), which would leave many communities that counted on its support in a situation of vulnerability. The third was also a motion to reject a policy, specifically towards collective warrantless frisking of residents and searching of residences in City of God, authorized by judicial order days before the event as a reaction to a confrontation between police and drug traffickers, considered a violation not just of human dignity and of the city, but of the right to housing and to the city. The last was a motion for the confection of a commemorative plaque to be installed at UERJ, where the event happened, in memory of the Favela do Esqueleto, removed in the 1960s for construction of the university.

Andreia concluded her intervention during the closing panel with a challenge: “I want to see who is going to put what is being discussed here in practice to change the reality of the favela. If it’s up to me, it won’t just stay in my memory. And I am sure that if it’s up to a lot of people here, it also will not.”