“Uma promoção pra você: dez Reais, três Antárticas!” “Queijo Minas! Queijo Minas! Cinco Reais!”

The calls of the vendors echo into the warm night over the hum of laughing revelers and the beat of live Samba bands. Under the low light, pedestrian traffic comes to a momentary standstill as a colorfully-dressed woman on stilts weaves her way through the crowd.

For a first-time visitor it might seem like a special occasion, but it’s just another Monday night at Pedra do Sal in Rio de Janeiro’s Gamboa neighborhood in the Port Region, a historic quilombo community known for being the birthplace of Samba music, and today site of one of the city’s most popular weekly street parties.

Rio’s world-renowned nightlife scene, like so many other integral aspects of the city, is marked by structural informality and improvisation. After dark, from Lapa to Gavea, Botafogo to Praça São Salvador, traditional venues become an afterthought as the street becomes the party in a mass of revelers, flowing cachaça, and impromptu music and dance performances.

Often overlooked, however, are the thousands of vendors across the city who supply the caipirinhas, skewered meat, and bottled water needed to keep the party alive and thriving until the early morning hours. Many of these workers are residents of favelas and the suburban Baixada Fluminense region, who commute long distances and operate outside of the traditional labor market as independent entrepreneurs, some by choice and others by necessity.

They are a mere fragment of the larger “informal economy” in Rio, which by some estimates encompasses around 60% of the labor force in this city of 6.5 million.

The ‘Informal Economy’: A Brief Introduction

While its name and scope are the subject of ongoing debate amongst economists and sociologists, the ‘informal economy’–also referred to as the ‘underground economy,’ ‘System D’ or the ‘grey market’–is an undisputedly massive force in the global economy. It is generally characterized by jobs that are unregistered and unregulated, unprotected by governments, often untaxed and dealing mostly in cash. It is a system spontaneous and improvisational by nature, seemingly chaotic but often held together by complex networks built on trust and self-organization.

When taken altogether, the informal economy amounts to the equivalent of US$10 trillion per year, making it the second largest economy in the world, after the United States.

And it is growing–rapidly.

In 2009, the number of city-dwellers around the world passed the number living in rural areas for the first time in history. With nearly all of the planet’s population growth concentrated in developing countries, demographers and economists estimate that over the next 15 years, cities in emerging economies will create 50% of the world’s economic growth.

In 2016, an estimated 2 billion people are working off-the-books worldwide. This confluence of demographic change, globalization and urbanization has created a modern global economy where by 2020, two out of every three workers will be informally employed, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

In Rio, the weekly street party at Pedra do Sal offers a look at the structure of a large informal economic ecosystem and a window into the lives and motivations of many of its individual workers.

‘Caipirinha! Caipirinha!’: Stories from Pedra do Sal

Leaning against his bicycle pushcart under the cover of a makeshift red umbrella, a young man discusses his business model.

“When I buy the beers they’re R$4 per bottle. Out here I can sell them for six, even seven if it’s crowded,” says Gabriel. “On a good night I make R$800 (US$240) in sales which is R$300 (US$90) in profit.”

Gabriel grew up and still lives in Duque de Caxias, a suburban city of nearly a million an hour north of central Rio, where due to the country’s current economic crisis, job opportunities in the formal sector for young people who lack an advanced education are scarce.

Instead, he improvises.

By making bi-weekly trips to a depósito, a restaurant-depot style outlet store, he can purchase boxes of Heineken, Brahma and Antárctica beer at manufacturer’s prices. Each Monday evening, he makes the journey to the home of his friend Francis in the nearby favela Morro da Providência, where he stores his product and pushcart.

“The goal is simple. I’m trying to sell everything in my cart.” he says. “Sometimes it takes a few hours, sometimes all night, but when I sell out I go home, because that means it’s been a good night.”

Francis, his more seasoned companion, laughs. “You’re lazy, man! If I run out early in the night and there are still lots of people and lots of movement, I take a taxi back home to reload my cart.”

For Gabriel and many of the other younger vendors pushed out of the formal sector, selling beer has become a full-time livelihood. They scour Facebook and other social media sites for parties and events and sometimes arrive hours early to set up their carts in the prime spots, as these go on a first-come first-serve basis.

But for others, moonlighting informally is simply a way to make ends meet in an economy that is increasingly oppressive to the working class. Brazil’s national minimum wage of R$5.85 per hour (roughly US$1.80) coupled with the rising cost of living in gentrifying cities like Rio has contributed to the continued growth of the informal sector.

Rafael, a middle-aged vendor at Pedra do Sal, has held a ‘formal’ job as a host and busboy at a downtown Italian restaurant for the past 22 years. He makes more than minimum wage there, but barely, earning around $1400 reais (US$415) per month. It covers his family’s basic living expenses in a nearby favela but leaves little lee-way for further investment in his family, like the private school he wants his two daughters to attend, given the low-quality nature of public education in Rio.

“Sometimes I can make more in a few hours selling caipirinhas than I do in a week of (formal) work,” he says. “Of course I would prefer not to work these late nights but it is worth it for me to help my daughters.”

Rafael’s situation is not unique. The profit margins in the informal sector can be surprisingly high, sometimes to the point that they draw workers out of the formal sector altogether.

A caipirinha-seller named Manuel described how he could purchase entire bottles of 51 Cachaça for R$8, then sell individual caipirinhas for R$8 each, with the bottle often lasting to make eight or nine drinks. Even accounting for limes, sugar, and transport to buy the materials, he still calculated his profit margin on each drink to be north of 600%.

“I used to just sell beer, but the extra work required to make the caipirinhas is worth the higher profit.”

These margins are not solely in the alcohol sector. Robert Neuwirth, an American journalist whose work focuses on informal markets, has found that the average street-level shoe merchant in Lagos, Nigeria has a higher profit margin on a pair of sneakers than multinational retailer Payless Shoes.

Structured Informality

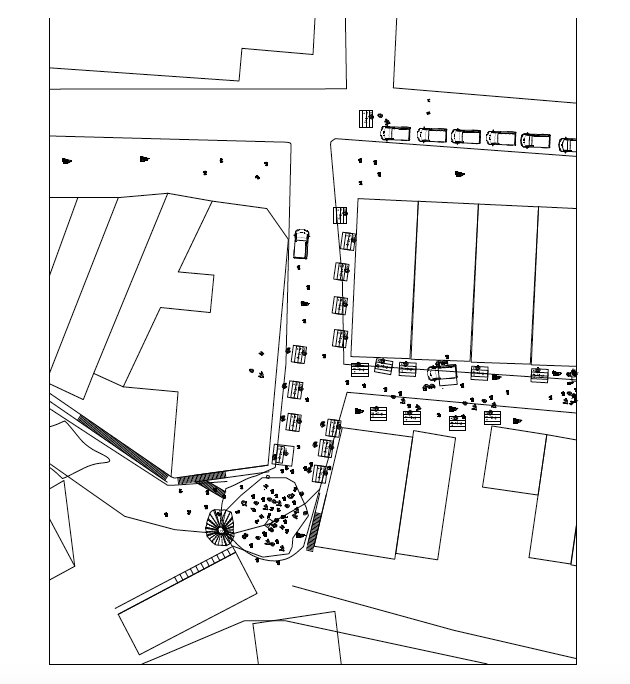

At Pedra do Sal, vendors coming from outside the community like Gabriel and Rafael operate on the margins of a layered, informal economic ecosystem capable of moving tens of thousands of dollars on a busy night.

At the most formal level are the two ‘brick and mortar’ bars on the main street, one of which doubles as a discoteca on party nights. Then there are a handful of homes that open up their garages to sell alcohol and snacks, often charging for use of their restrooms. At the street level, selling spots at the street’s central intersection are reserved for twenty red and white barracas, or tents. To operate a barraca one must live in the community itself, and in an informal licensing system of sorts, must pay R$50 (US$15) to a man who stores the tents and provides ‘security’ services.

If a vendor from outside the community like Gabriel tried to set up his cart in a prime barraca spot, this man would kick him out. Operating a barraca at the street’s main intersection has its benefits: vendors here report making R$2000 (US$600) in sales, R$1200 (US$360) in profit per night, typically split amongst the two or three people working the stand. Furthest from the center of the action are the pushcart and bicycle vendors who are not residents of the community. They operate near the entrances and exits of the street.

A ‘vendor-service’ side economy has emerged around the informal selling tactics. Manuel described how he pays a man who owns a nearby warehouse R$50 per week to guard his bicycle cart and extra product, which is too cumbersome to bring up the steep hill to his home in a favela each night. The fee covers both storage and insurance–these types of warehouses have been subject to raids by the city government in recent years–but Manuel’s agreement with the owner ensures he would be compensated were his goods seized.

A lexicon has developed as well: street merchants are referred to as ‘camêlos’ and the goods they sell are often said to be ‘de Paraguai’ (‘from Paraguay‘–seen as many come from the black market in Ciudad del Este, Paraguay, a city at the borders of Paraguay, Brazil and Argentina dominated by Brazilian, Chinese and Lebanese merchants).

Policy Debate: Is formalization the right path for all?

Street vendors are the most visible players in the informal economy, so it is unsurprising that they were central targets of the city’s sweeping efforts to formalize and ‘cleanse‘ its image (see: “É Para Inglês Ver”) prior to the World Cup and Olympic Games. Mayor Eduardo Paes made this a priority from early on in his tenure, enacting a variety of legislative decrees to regulate street trade and register street vendors.

Meanwhile, the federal government established the Micro-empreendedor Individual (MEI) licensing program, which attempts to encourage informal workers to formalize in a tax-exempt manner and begin receiving government benefits for a monthly fee. Universally praised for its simple and non-bureaucratic online registration process, the license also offers access to the financial system through the ability to create a bank account, fee-exempt online business creation, and subsidized credit card point-of-sale machines for street vendors.

Irenaldo da Silva, president of the residents association in the North Zone favela of Pica-Pau, where a large portion of residents work informally, believes the licensing program is a step in the right direction: “This is a government policy that I am in favor of. I encourage everyone in the community who is running a business to sign up because there are many benefits.”

A local shopkeeper named Roberto agreed. “I used to sell clothes, but because of the crisis, people in this community don’t have extra money to buy new clothes, so I recently switched my business to sell office and school supplies,” he said, showing off his new shop full of notebooks and other school essentials. “I applied for the (MEI) license and because I had it, I got discounts on wholesale products to start this store.”

But some business-owners in his community remain unconvinced. A resident named Marcelo who runs a rotisserie chicken shop out of the front of his home complained that he had paid the R$45 monthly fee for the license but received no benefits. Da Silva acknowledged that some business owners in the community did not seem to fully understand what they were entitled to under the program and thus resented it.

Lack of awareness surrounding the benefits of the program could be an explanation for its relatively low level of adoption. Another possibility, suggested by Social and Political Studies professor Adalberto Cardoso is that for people whose entire sociability was formed in the realm of informality–from housing to access to electricity to their overall relationship with the state–becoming formalized and thus ‘visible’ to an untrustworthy government is seen as undesirable and costly.

Other critics of the MEI contest that it contributes to the criminalization of poverty. In the revitalizing neighborhood of Lapa, the city partnered with Antárctica, a major beer brand and subsidiary of the AMBEV group, to create a ‘Night Market’ of 82 vendor stalls, with the sponsoring brand reserving exclusivity over beer sales. Vendors operating outside of the 82 formalized stalls have been subjected to frequent police crackdowns in which their carts and product are confiscated.

Many vendors across the city spoke of being afraid to work there anymore, despite its huge weekend crowds and business potential.

The relationship between governments, corporations and the informal economy will play a critical role in shaping economic development in the 21st century. Rather than subjecting informal entrepreneurs to blanket condemnation and forced formalization, an attempt to better understand the value of informality in labor is a critical first step towards designing the policies that will guide and sustain the modern global economy.