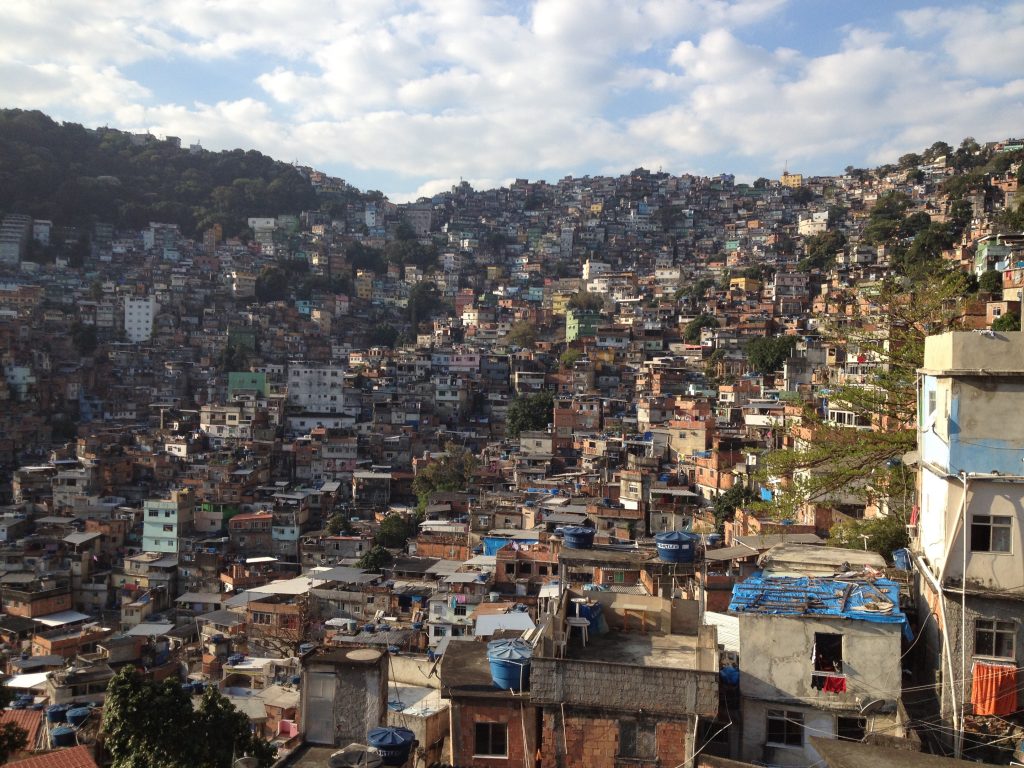

The rooftop balcony of the Roupa Feliz hostel offers a rare refuge from the heat and bustle of the Rocinha favela. Due to its sheer size, Rocinha is often referred to as a city within a city. The sky teems with kites as children tug at the strings from their respective lajes, or rooftops. The shade of mango trees of the hostel and the surrounding garden provide a refreshing cooling effect in an otherwise tightly knit and densely packed neighborhood.

But the site of Roupa Feliz is not just a friendly and peaceful abode for tourists curious about life in Rio’s favelas. It is also a significant source of sustenance for a long-standing community project and daycare center in the Rocinha neighborhood of Roupa Suja, or Dirty Clothes, a name originating from that fact that there was no water source there and residents had to climb down the hill to wash their clothes in years past. The project is called União de Mulheres Pro Melhoramento da Roupa Suja, (UMPMRS), or Union of Women for the Betterment of Roupa Suja. It is at once a daycare, preschool and community center, providing a wide array of holistic and comprehensive services to families, including but not limited to: “knowledge workshops” for youth, involving after-school support, English classes, and a computer media lab; assistance from social workers, pediatricians, psychologists and other health care professionals; weekly support groups for adolescents; and accessible, high-quality care and education for the children and families of Roupa Suja to grow and thrive.

The history of this community safe haven stretches back to 1978. Born and raised in Rocinha, founder Marcia Ferreira da Costa says her life’s work began at 12 years of age. Since her mother worked at a private school in Rio, Marcia had the rare privilege of attending private school and was therefore able to access good quality education. In those days Rocinha was receiving a large influx of migrants from the Northeast of Brazil fleeing drought and famine and flocking to Rio in search of work. Many of these northeastern migrants had never learned to read or write, so they turned to Marcia to read letters coming from the northeast and to write back to loved ones in far away regions. “Our house was small, just three rooms. My father said, ‘It’s going to be even smaller than it already is, but you aren’t going to hand out fish anymore, you will teach how to fish.’ This is how I started to teach adults how to read, and later they brought their children so I could teach them as well,” explains Marcia.

Her work quickly evolved into a daycare and after school program for children in the neighborhood. By 1993 she had over 40 children and three babies in her care in her home. That year she was able to move her services to the nearby church. In 2000, the União de Mulheres acquired the building it has today. “Only education can take you anywhere in life. Education has transformative power. When you have education, your life improves, everything improves,” asserts Marcia. According to Marcia, the name of the project pays homage to the women heads of household, who understand this transformative power of education.

There are currently 48 children enrolled at União, though in past years when there was more funding enrollment rates reached as high as 80. The daycare services are available for infants as young as 4 months up to children 6 years of age, and is open from 8am to 5pm. Children are provided balanced and healthy meals for breakfast and lunch and a wholesome, nutritious afternoon snack. They are also bathed and changed into a fresh set of clothes everyday.

Separate classrooms for different age groups provide ample space to learn and play, and cater to varying developmental stages. There is a library and rooftop balcony where special community events take place. And there is the garden, playground, and toy library of the Roupa Feliz hostel that children are free to access as well. “Often when children come for the first time and they see these large rooms they run from one side to the other. They don’t have this kind of space at home or on the street. Just one of our nurseries is usually bigger than their entire house,” explains Marcia. Parents contribute what they can every month, though the majority are unable to make any financial contribution. Those who have the means offer anything from R$50-160 on a monthly basis. In all, total contributions from families only account for about 10% of the daycare’s budget.

The weekly support group called Adolescentes Sem Fronteiras, or Adolescents Without Borders, was initiated in an effort to create a safe and nurturing space for teens to bring forward and discuss issues concerning drug trafficking, dating violence, teen pregnancy, and sex education, among other topics. Today several staff members were once children at the daycare. Generations of families have benefited the services of União, and Marcia’s own great-grandson who is just two years old is currently enrolled.

While the daycare maintains a long history in the community and has never had to close, keeping its doors open is nothing short of a daily challenge. Even if every family had the means to pay the monthly fee of R$160, this would not be sufficient to cover the costs of meals, let alone teacher salaries. Were it not for the mutirão, or coordinated and cooperative efforts of the community, creative self-resourcefulness, and quick adaptation to ever-changing demands, the project would not have survived. “I’ve had to care for children in my house before, I’ve collected and sold cans in order to pay teacher salaries. I’ve gone without my own salary, I’ve taken up janitorial duties, I’ve sat in for teachers, I’ve done everything to keep the daycare alive,” recounts Marcia.

The União de Mulheres funds its work from a wide variety of sources. With the help of international partners and volunteers they have been successful in applying for grants from international NGOs and obtaining donations. They have a partnership with a local favela tour group that provides all the meals free of charge. However these partnerships are in a constant state of flux and risk being discontinued at any moment, which places the daycare in a precarious situation everyday. As vice-president Maria do Carmo de Farias Barbosa, otherwise known as Carminha, explains, “International donors often want to purchase a new building for us. But how do we maintain such a building? How do we even maintain what we already have, when our costs are already so high? What we need is to maintain what we have, in an excellent matter, and good ideas for capturing more funding. Only after can we consider expanding to an additional building.”

A few years ago União decided to create a hostel in order to have a more autonomous, steady and dependable flow of revenue for the organization. It accounts for more than 20% of the financing of the organization, and has proven to be a vital instrument in keeping its programs afloat. At its inception the idea of the hostel was for guests to also volunteer at the daycare as part of their stay. While this is no longer a requirement, guests continue to offer their service to the daycare, including painting walls and murals, helping deliver and stock materials and food, and animating recreational and educational activities for the children.

Nevertheless, funding remains a never-ending obstacle. The dream of the women of União since its inception is to become a publicly-funded daycare. “As a public daycare the municipal government would provide us with R$300 per child every month,” explains Marcia. The women have hung onto this dream tenaciously, despite its many challenges. To achieve public status, the daycare must undergo a very complicated and bureaucratic process, and meet strict standards and requirements. Staff must be paid on the books, which has not been the case, and all teachers must have formal training and a degree in order to teach.

While the public funding would certainly help the project sustain itself, this alone would not free it from dependence on outside sources. With any public institution in Brazil, delay of payments is all too common. In fact, in order to even secure an agreement with the municipality, the daycare must attest that it is capable of holding its own financially should the funding arrive late, as it inevitably does. There are several public daycares in Rocinha, and staff regularly endures three, even four months, without pay. “I don’t want this to just be a depository for children. I want to provide high quality education. If I wanted I could accept more children and have up to 30 kids crowded in the room above. But I don’t, I want to maintain a high standard. Space I have, we have plenty of that. What I need in order to help more children is more teachers,” explains Marcia.

In 2016 the daycare established a partnership with a Brazilian nonprofit called Instituto Phi, which stands for Philanthropia Inteligente, or Institute for Intelligent Philanthropy. They search for high quality social projects to then connect with Brazilian companies wishing to donate money to philanthropic causes. The organization follows the social projects throughout the application of donated funds and generates reports for donors to review the implementation of the projects they are supporting. Phi selects organizations that meet criteria in four domains: transparency, quality of management, impact and solidity. As it stands now Phi has made partnerships with 49 investors, contributing to over 168 projects in Brazil and generating over R$9.5 million for the charitable sector. Phi has been assisting União in reaching required regulations and standards in order to become a public, municipal daycare. This means addressing the entangled electrical wires at the front of the building, installing water cisterns, and constructing safety fences on balconies and rooftop terraces. These three goals have already been achieved. However, with the state of Rio de Janeiro declaring bankruptcy, and the current post-Olympic financial crisis in the city of Rio, along with Mayor Crivella’s promises to cut public expenditures, there is concern with the government’s political will to fund social projects like the União de Mulheres. Yet again, União’s dream has been put on hold.

“I come from a family that had every reason to quit. I’ve had so many reasons to not keep going. But my message to young people is to never give up,” reflects Marcia. The União de Mulheres is a testament to the creative, flexible and self-resourceful nature of favelas in Rio as they respond to the absence (and at times hostility) of the state, a lack of resources and challenging circumstances.