Although Bárbara Nascimento is a friend and co-organizer with André Gosi in Vidigal, a South Zone favela which has experienced significant gentrification in recent years, “no one has the slightest idea” about the name of the street where he lives. Nascimento, a teacher and current Master’s student born and raised in Vidigal, uses a set of well-known reference points throughout the favela to locate the homes of other fellow residents. Even when describing her own address to others, Bárbara “only says that she lives in Pedrinha” (Little Rock).

This system of urban mapping speaks to the greater context of Rio de Janeiro, where favela culture is impacted by tensions between community narratives and those pushed by the government. In Vidigal, this friction extends to the politics of location, as city regulations and initiatives often contradict resident needs. The government once tried to give fruit-themed names to streets in Vidigal in the 1990s. As Nascimento explains, this proposed change was blind to the fact that many residents from Vidigal struggle to find jobs when their addresses are recognizable as belonging to a favela. “There was already this issue of prejudice towards residents, and you want to name it Banana Street?” Meanwhile, community-driven attempts to name Vidigal’s streets after living local heroes have been shot down by a government mandate that only allows deceased individuals to be commemorated.

Fast-forward to 2012, when German graphic designer André Koller experienced the challenge of tracing the informal community while designing a local map called “Vidigal: 100 Secrets.” Seeking to more accurately place important landmarks on his map, Koller began to research the various reference points of Vidigal, finding “that there were rich stories behind the majority of these locations.” Koller then reached out to Nascimento as a research partner, and eventually a new idea was born: to install strategic and artistic plaques at each of these important locations.

Fast-forward to 2012, when German graphic designer André Koller experienced the challenge of tracing the informal community while designing a local map called “Vidigal: 100 Secrets.” Seeking to more accurately place important landmarks on his map, Koller began to research the various reference points of Vidigal, finding “that there were rich stories behind the majority of these locations.” Koller then reached out to Nascimento as a research partner, and eventually a new idea was born: to install strategic and artistic plaques at each of these important locations.

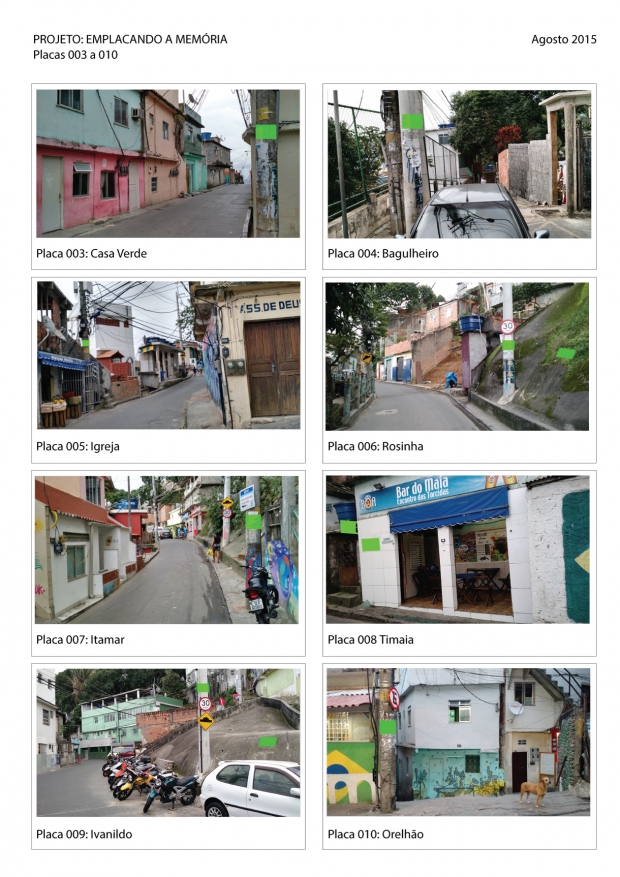

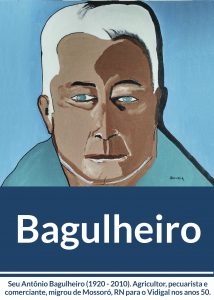

From here, Koller and Nascimento contacted Gosi, who oversees culture at the Vidigal Residents Association, to join the project. 42 plaques have been selected, commemorating different areas in Vidigal, with two already designed. Eight local artists have confirmed their participation in the initiative, with five more expressing interest. Artists will have the freedom to choose the areas they want to commemorate, as well as the design of the plaques, and their work will be done on a volunteer basis. A crowdfunding campaign is directed towards purchasing materials to bring these plaques to life.

Nascimento, Gosi, and Koller say they have three goals: to preserve memory, to accomplish a project of upgrading that the city of Rio is reluctant to undertake during a moment of crisis, and to pay homage to local heroes and figures of importance in an effort to give residents a sense of identity and build community pride. Plaques will also serve as physical reference points to reinforce the collective knowledge and history surrounding each location.

As such, an overarching aim of the project is to, as Nascimento put it, “legitimize the distinctive logic of the favela.” Due to its decades of informality, Vidigal presents logistical challenges to an outsider that are nevertheless surmountable. “When we buy something from a store and need it to be delivered here, we give them the street and the area. Businesses understand the reality of the neighborhood” while the government refuses to. Unofficial streets in the favela, though they receive a CEP (zip code) designation, are not recognized by their community names by the authorities, which makes receiving services extremely difficult. Through their campaign, Nascimento and Koller hope to achieve more mainstream recognition for Vidigal, as well as inspire other favela communities to take similar actions.

As a historical project, however, this initiative will serve a function specific to Vidigal. Collecting and making memories like these permanent is vitally important in a time when Vidigal is facing increasing gentrification and the first generation of inhabitants is rapidly aging. As Koller puts it, “A resident’s life is the story of Vidigal.” Without documentation, in a few years, firsthand knowledge of the crucial years of the favela’s formation will be lost.