“In theory it sounded like one of the most innovative models for including citizens in the democratic decision making process,” one Federal University of Rio doctoral candidate told me. Her research focuses on participatory processes in the favelas pacified under the Pacifying Police Units (UPP). She continued: “But spending a year closely following meetings between residents and the government showed me that it was just that: participatory only in theory.”

“In theory it sounded like one of the most innovative models for including citizens in the democratic decision making process,” one Federal University of Rio doctoral candidate told me. Her research focuses on participatory processes in the favelas pacified under the Pacifying Police Units (UPP). She continued: “But spending a year closely following meetings between residents and the government showed me that it was just that: participatory only in theory.”

Citizen Participation

Democracies require some degree of public involvement. Citizen participation is a complicated concept, because it is not a well-defined ‘thing’ but rather a scale of different degrees of inclusion of citizens in democratic decision-making processes. It runs along a continuum, from near zero inclusion in dictatorships, to greater inclusion in democratic states.

But there is much discussion about the place for citizens along the continuum of a nation’s affairs. In some places there is even confusion of ‘consumer’ with ‘citizen,’ some believing participation in the market is a viable primary vehicle for democratic expression. More common, however, is the premise that participation should be realized mainly through elections. In this case it is believed that showing up to vote every 4 years suffices, if there is a diverse party or candidate pool, large numbers of voters head to the polls, and the election process is generally well carried out.

The problem with both of these approaches is that they issue a severely limited role for citizenship. The market reduces citizens to consumers, expressing their wishes solely through consumption of goods and services, offering them little true influence on the creation or allocation process. This also assumes that those holding wealth (and thus consuming more) should have more ‘say.’

An elections-focused approach limits participation to the electoral process, seeing citizenship as expression solely in the political arena on a fixed schedule, which consequently also facilitate electioneering (actions by politicians made specifically to sway the vote).

A third approach exists, however, which serves to deepen democracy and move away from this dichotomy. This approach holds that in order to produce efficient and effective policy results citizens need to be included throughout the decision-making processes that affect their lives.

Participation under the UPP in Vidigal

The UPP Social, the social complement to policing offered by the UPP pacification policy which has already been introduced in some two dozen of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, is presented under the banner of this “deeper approach.” One of the program’s three primary goals is to “involve residents of the community in the process of integrating them into the city at large.”

Since February I have been actively attending UPP Social participatory meetings in Vidigal, a particularly picturesque community overlooking Leblon beach in Rio’s South Zone.

Conversations between the community and the UPP take several forms, primary of which are meetings between the community and those responsible for the UPP Social program. It is at these meetings that the lack of substantive interaction between the UPP and residents of the favela is most visible.

On February 15th I went to Vidigal to join in one of these meetings between the community and the UPP social, only to be informed on arrival that the meeting had been rescheduled for the next day. This surprised me as it did the other thirty people that had shown up expecting to attend the meeting.

I returned the next day to find the meeting happening, without the presence of any of the UPP Social representatives, who had canceled half an hour before the meeting.

March 2nd there was another attempt, this time with the presence of UPP Social officials. The meeting took place in the building of the well-known Nós do Morro NGO in Vidigal. The space normally used for rehearsals was filled with some 120 chairs. The room was packed, with people standing in the back. The personnel of the UPP Social program introduced themselves and explained they were there “to initiate an exchange of ideas between the government and residents of Vidigal and Chácara do Céu.” A PowerPoint presentation was made by the UPP Social team.

The first interaction between the public and UPP Social team occurs when a slide displays the estimated population living in the two communities. According to data in the hands of the government officials, the total comes out to 10,372 residents in the two communities combined. When discussion erupts it is cut off by Ricardo Henriques, head of the UPP Social and President of the Instituto Pereira Passos (IPP), with the words, “These are the numbers of the IPP and the IBGE (Brazilian census bureau), and they are right.”

When I speak to one of the community leaders after the meeting about the number of people living in Vidigal and Chácara do Céu he tells me that to him, “The government uses these low estimates because fewer people means having to invest less resources. And as our neighbor (Rocinha) is somewhat of a problem child, they prefer to put their resources, time and energy into that community. We are being punished for being smaller and better organized.”

A second conflict that arises is the difference in priorities held by the UPP Social and the community. The UPP Social has determined the focus should be on improving garbage collection, the formalization of payments for electricity (whereby residents now pay their electricity and other utility bills), and the improvement and renovation of public space.

The three primary demands of the community, however, are education, access to health care and attitude of the police towards the inhabitants of Vidigal and Chácara do Céu. Several representatives of the community spoke about the attitude of the UPP police officers being the same as that of the ‘normal’ police that interacted with the community when it was still controlled by drug gangs.

As one resident of Vidigal and representative of the youth movement “Cidade Unida” (United City) said during the question rounds, “We had expected the attitude of the UPP officers to be different. We had expected them to treat us with more respect, yet the other day I saw one police officer put a 10 year old boy against the wall to body search him, which is illegal. And every day I see the police cars passing with the loops of their guns sticking out of the window, pointing at whomever happens to be passing by on the street. These attitudes scare us and make us doubt all these beautiful words of ‘dialogue’ and ‘working together’ that have been expressed in this meeting by the UPP Social team.”

As one resident of Vidigal and representative of the youth movement “Cidade Unida” (United City) said during the question rounds, “We had expected the attitude of the UPP officers to be different. We had expected them to treat us with more respect, yet the other day I saw one police officer put a 10 year old boy against the wall to body search him, which is illegal. And every day I see the police cars passing with the loops of their guns sticking out of the window, pointing at whomever happens to be passing by on the street. These attitudes scare us and make us doubt all these beautiful words of ‘dialogue’ and ‘working together’ that have been expressed in this meeting by the UPP Social team.”

Effective participation is not happening because even though the UPP Social program states an intention to increase dialogue and participation of favela residents, this is only one of its three aims, and effective participation would imply a deliberative contemplation over the other priorities. The other two aims of the UPP are (1) to improve security (for those within but also outside of the favelas) by “taking back control of the communities from the gangs,” and (2) to formalize and integrate the favela communities into the formal city by providing missing public services. Rather than recognizing that effective deliberative participation is an essential ingredient for the successful implementation of these other two aims, governing officials view it as a distraction and a box to be ticked in the process of implementing other priorities.

At the meeting in Vidigal this became evident when the community formulated their main issues to be tackled (education, health, police conduct) only to be told by Tiago, the UPP Social official responsible for all issues concerning land management, that “There are things we can do today, and there are things we cannot do today. Some things are more pressing than others, and we believe that we should first resolve the issues concerning electricity and garbage collection, and the improvement of roads and houses.”

Or as one resident sitting next to me ‘translated’ for me: “They have contracts with Light (electricity company) and Comlurb (waste collection company), providing these services that they say are ‘essential.’ They are only essential for their wallets.”

Whether true or not, the fact is that of the 23 questions asked by residents during the question round only three were answered. The others “would be gotten back to.” Yet to this day, a month and a half later, no response has been given.

Arguments for Limited Participation

Some say that the UPP Social officials have a good point, that it is not possible to listen to all the residents of Vidigal (whether it be their 10,372, or the residents’ estimate of 15,000) and that citizen participation doesn’t mean involving all citizens in all decisions at all times and at all cost.

This argument is systematically used by the UPP and is based on the assumption that democracy and citizenship need to be invested in quantitatively instead of deepened qualitatively.

Another platitude is that full participation is not possible in a country like Brazil with a history of dictatorships and a system of democracy that is unable or unwilling to respond to the needs of the large majority. According to this logic, the UPP Social constitutes a huge ‘advance’ in the fact that the state meets with residents at all.

Brazil as a Participatory Model

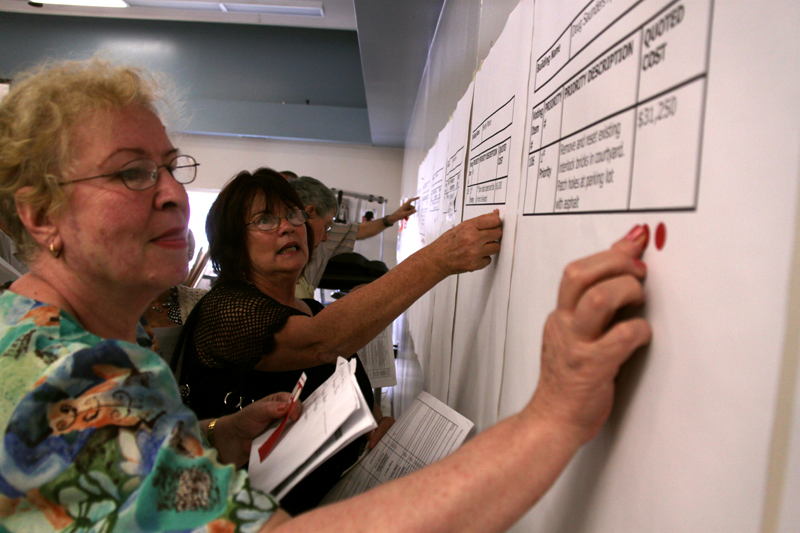

Since implementing the first participatory budgeting process in the world in 1989, Brazil’s city of Porto Alegre has become a symbol of deepening participation. Since then, more than 1200 municipalities worldwide have followed suit with participatory budgeting initiatives, most recent of which are New York and Newcastle. It is possible, even in the Brazilian context, to involve citizens in the decisions that concern them and it is possible to change the system to engender active participation of the majority. In fact, perhaps it is even more necessary in the Brazilian context. It was Porto Alegre’s high inequality that gave rise to the initiative in the first place. There, sewerage and water connections, education and health networks expanded dramatically thanks to participatory budgeting. And two decades after the initiative began, participation continues to be high.

Since implementing the first participatory budgeting process in the world in 1989, Brazil’s city of Porto Alegre has become a symbol of deepening participation. Since then, more than 1200 municipalities worldwide have followed suit with participatory budgeting initiatives, most recent of which are New York and Newcastle. It is possible, even in the Brazilian context, to involve citizens in the decisions that concern them and it is possible to change the system to engender active participation of the majority. In fact, perhaps it is even more necessary in the Brazilian context. It was Porto Alegre’s high inequality that gave rise to the initiative in the first place. There, sewerage and water connections, education and health networks expanded dramatically thanks to participatory budgeting. And two decades after the initiative began, participation continues to be high.

It is not only in participatory budgeting that Brazil has made a name for itself. Brazilian political scientist Thamy Pogrebinschi wrote in a recent paper on Brazil’s national public policy conference process that: “Participation seems to have indeed become a democratic method of governance in Brazil. As a method, participation enriches representative democracy. While turning political institutions into more representative bodies, this participation accommodates civil society within the state, and impels the redesign of both policymaking and lawmaking processes. Such institutional changes have for their turn been proving themselves to produce not only more legitimate political decisions, but also more effective social outcomes. If Brazil’s noted poverty reduction is due to income transfer and other successful redistributive policies adopted by Lula’s government, the political representation of minority groups (such as women, indigenous people, LGBT, elderly, youth, people with disabilities, among others) is certainly also an achievement of the institutionalization of participatory experiences that allow for a more stronger and effective advocacy of rights and policy inclusion.”

Rio as an Exception

Rio de Janeiro, however, is marked by a historic lack of participatory process and the UPP Social forums are no different. The fact that the UPP Social does not incorporate resident suggestions made in its public debates and executes only those programs set by UPP policy at large is not a question of lack of capacity to address and incorporate favela citizens’ needs but an unwillingness to do so.

This is unfortunate because by not listening to the demands of favela residents policy makers are missing out on the opportunity to actually integrate the favelas into the formal city. I have observed across the UPP Social forums I’ve been to the large number of community residents in attendance, more than willing and capable to join in the state’s decision-making processes.

UPP Social in theory has the structure to incorporate and execute demands of favela residents. And Brazil’s experience, as the ‘darling’ of the international participatory democracy movement, shows this is feasible in practice. But with no tradition of deliberation and inclusion in a city whose inequality hasn’t changed despite Brazil’s eight percentage point decline in inequality, it doesn’t look like change is coming yet. At least not via UPP Social. Maybe it is too much to expect that a program bent on ‘pacification’ would give people a voice.

Recommended Reading

Cornwall, Andrea; Coelho Vera

2007 Spaces for change. London: Zedbooks.

Giddens, Andrew

1985 The Nation-State and Violence: A contemporary Critique of Historical materialism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Isin, Engin F.; Turner, Bryan S., eds.

2002 Citizenship studies: An introduction. In Handbook of citizenship studies. Isin, Engin F. and Turner, Bryan S., eds. Pp 1–10. London: Sage.

Jelin, Elizabeth, eds.

1996 Citizenship revised: Solidarity, Responsibility, and Rights. In Constructing democracy: Human rights, Citizenship and society in Latin America. Elizabeth Jelin and Eric Hershberg, eds. Pp. 101-119. Colorado: Westview Press.

Pogrebinschi, Thamy

2012 “Participatory Policymaking and Political Experimentalism in Brazil”. In: Stefanie Kron/Sérgio Costa/Marianne Braig (Hg.): Democracia y reconfiguraciones contemporáneas del derecho en America Latina. Frankfurt/Madrid: Vervuert (i. E.).

Sadek, Maria

2000 Justiça e Cidadania no Brasil. São Paulo: Sumare.

Tilly, Charles

1985 War Making and State Making as Organized Crime. In Bringing the state back in. Peter Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer and Theda Skocpol, eds. pp. 169-186. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.