When Pollyana de Oliveira, 28, gave birth to her third child, she had no idea that something might be wrong. Neither did she have any problems during her pregnancy, nor any disturbing ultrasounds. But when Luiz Phillipe was born, his head was unusually small for his body size, not much bigger than an orange. He has Zika-related microcephaly, a birth defect that leaves children with small skulls and malformed brains and frequently causes severe developmental problems.

Pollyana only found out afterwards that what she perceived as a common flu in her 8th month of pregnancy must have been Zika. At that time, in November 2015, no one knew about the effects that the disease might have. Compared to other diseases spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, like dengue and chikungunya, the symptoms even seemed relatively mild. One in five infected people in fact do not show any symptoms at all.

Just some months after Luiz’s birth, in the run-up to the Olympic Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro, Zika became a worldwide talking point: pictures of babies with tiny heads were published, international flight companies gave mosquito warnings before landing in Brazil and the government declared a state of war on the small insect. During the climax of the world’s concern about Brazil’s Zika outbreak 100 doctors and professors wrote an open letter to the World Health Organization, asking to postpone or cancel the Games: “We make this call despite the widespread fatalism that the Rio 2016 Games are inevitable or ‘too big to fail,'” the writers said in the letter addressed to Director-General Margaret Chan. “Our greater concern is for global health. The Brazilian strain of Zika virus harms health in ways that science has not observed before.”

By that time, Pollyana thought that it might seem a bit hysterical, but at least the world seemed to care. Now her feelings have changed. Like a lot of other mothers of microcephaly children she feels that “no one cares about us.”

According to Brazil’s social assistance policy, mothers of children with disabilities with an income below R$220 per month are entitled to a minimum wage of R$880. Pollyana applied for the public benefit a year ago, but she has yet to receive any support.

The only governmental support she got was a small apartment in a Minha Casa Minha Vida building in Maricá, on the outskirts of Niterói, Rio de Janeiro’s sister city across the bay. Here she lives with her three children, including Luiz, paying about R$80 in monthly rent. Since caring for Luiz is a full-time-job, Pollyana had to leave her work as a doorwoman in a discotheque. Luiz’s father is unemployed. He doesn’t live with the family, although he visits every day.

It costs R$14 just to get to nearby Niterói by public transit. Pollyana cannot afford a car, so she stays home most of the time.

Low-income families like Pollyana’s are most affected by Zika and its consequences. Impoverished rural areas and urban favelas have experienced the most cases among the 1638 cases of Zika-related birth defects across the country last year. And single mothers are carrying the main burden.

But Pollyana doesn’t complain. Instead, she finds solidarity and support in two Whatsapp groups of mothers with microcephaly children. One with 73 mothers based around Rio de Janeiro, another including mothers all over Brazil. “I can´t even read all the daily messages,” she says. “Some of the members have become friends, others drop out of the group because their children die and they can’t stand staying in the group.”

She calls her son “o meu principe,” her little prince. To her, “he is a normal child, the microcephaly is just a detail. There are limitations, but I wouldn’t say he couldn’t overcome these.”

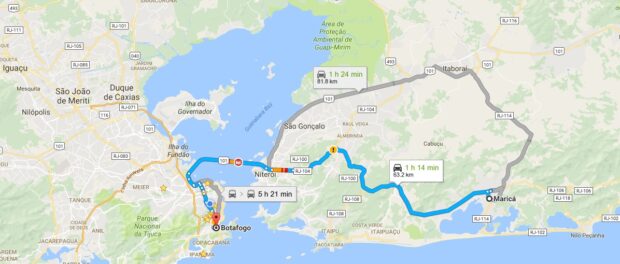

To get the medical treatment Luiz needs, Pollyana has to take a far and expensive day trip, five hours each way on public transit. The only public health center dealing with microcephaly is the Fernandes Figueira hospital in Botafogo, in Rio’s South Zone. The transport alone costs R$40 and she has to take someone else with her due to the difficulties of managing the baby with microcephaly on one’s own. When Luiz was little, she went two or three times each month, now a bit less.

But to get a chance of learning how to sit, grab and hold his head on his own, Luiz would need physical therapy on a regular basis. And to make that happen, Pollyana would have to pay for it. In the private health system, an hour of physiotherapy costs about R$400.

The younger Luiz is, the greater the benefits would be for him were he to access better treatment. Maria Elisabeth Moreira is a researcher at the Fernandes Figueira hospital. She stresses the importance of early facilitation for children like Luiz: “We get a window of opportunity to do something for these children within the first year, when the brain is developing. In this time, an affected area can be replaced by another… These children born during the Zika epidemic aren’t a lost generation… They deserve to be accompanied and stimulated to reach their full abilities.”

But during the economic crisis that Brazil is suffering, the public health system is almost collapsing. Moreira says that “millions have been spent for the development of vaccines and the war against the mosquito. The affected children have been forgotten.”