Last Saturday, May 7, the Fala Akari Collective and Acari Residents’ Association organized a Public Audience to hear what residents had to say and to report crimes carried out by the State in the community. The setting chosen for the event, the Favo de Acari Samba School, was a symbolic choice because the spot marks the site of the Acari slaughter of 1990; an event that has gone without consequences for its perpetrators. The event opened with a memorial to favela victims of police violence; their names called out and responded to with loud cries of “present.”

In addition to this unresolved crime, residents used the space to denounce others, like the death of thirteen year old Maria Eduarda, struck by four bullets whilst sitting in class at her local school. “I wasn’t afraid to speak up before, and now I really am not! No one will shut me up!” Rosilene, the girl’s mother said into the microphone. “When the Mayor says he’s going to bulletproof the schools, it’s laughable! We don’t want that, we want a bulletproof society. We want the presence of City Hall beyond just the police,” asserts Leonardo, teacher in the municipal school where Eduarda was assassinated.

Various people echoed this sentiment and the need to find a solution, not for policing but for investment in health, especially mental health provisions, and education. “How can you not have a technical school or university in a favela yet you can afford to fund a massive police operation?” questioned Estevão, resident of Acari. Other residents complained that the Ronaldo Gazolla Municipal Hospital, whose management was involved in embezzlement scandals in 2015, has no psychological services and is nothing more than a white elephant while the local schools and day care centers suffer from a chronic lack of provisions, classes, and teachers. Lennon, a member of the Deley de Acari the Poet Cultural Centre (CCPD) also denounced the vacating of the community’s first college preparatory course due to violence. One of the questions brought forward for discussion at the event was, “How can we maintain a public security policy without armed conflicts interfering with the continuity of the school calendar?”

Recurring property invasions without a court order, using skeleton keys or cropping locks, also appeared on the order of the day in the speeches of several residents. “When we get home, it’s all turned upside down. When we go out to work for the day we’re already in a state of fear,” said Janete. Residents claim that the invasion is often followed by the seizure of personal documents, using the residence as a hideout, and even a secret jail space.

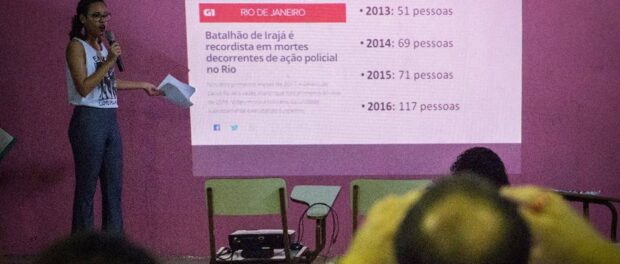

Rio’s North Zone has the highest death rates from police action (new term for ‘acts of resistance’) in the city. The 41st Battalion of the Military Police, which operates in the area, is considered the most lethal battalion in all of Rio de Janeiro and residents say it is known for practicing heavy-handed policing and taking in police officers from other battalions who are involved with problems and are still the subject of investigation. In the first three months of 2017 alone, the battalion executed at least thirty-six people.

Estevão reported: “Everyone who lives here has seen a pool of blood or a dead body. There’s drug taking and trading in Barra and Leblon [wealthy neighborhoods]. But it is here where there are gunshots, death. Sometimes, people convince themselves the war is normal but it is part of a system that is putting money in someone’s pocket, and it’s certainly not in ours. This war involves everyone but it only gets implemented here.” Another resident added, “The form of repression against trafficking is a political choice. If the traffic was over, they’d just find another reason to kill us.”