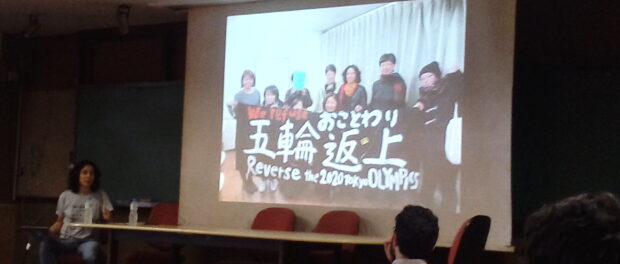

Although the Olympics are long gone in Rio, a legacy remains of incomplete infrastructure, evicted residents’ struggle for fair compensation, and the aftermath of displacement. The Games move on to increasing opposition in future host cities, both committed and prospective, along with criticism in the media. The category of Anti-Olympics activism has expanded with opposition groups seeing the opportunity to team up with one another all around the world, with an international Anti-Olympics coalition growing over the past half-decade, with contacts in Rio, Vancouver, Chicago, London, Sochi, Pyeongchang, Los Angeles, New York, Toronto, Boston, Barcelona, Paris and Tokyo. On May 29, the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) hosted Misako Ichimura of the Hangorin No Kai / No to 2020 Tokyo Olympics movement to discuss anti-Olympics efforts in Tokyo.

Giselle Tanaka, representative of Rio’s Popular Committee on the World Cup and Olympics and urban planning researcher at the Laboratory on Labor, Territory and Nature (ETTERN) at the Urban and Regional Planning Research Institute (IPPUR) at UFRJ, had previously visited Ichimura’s organization in Tokyo. She began the event with a presentation of her reflections on the visit. Tanaka explained that the movement in Tokyo “brings together different struggles” with various motives for rejecting the Olympics. While some opposed the Olympics for the event itself, others were most concerned with the preservation of historic sites and architecture in Tokyo, while still other groups worried about the effects of gentrification and privatization of public space, or the nationalism inherent in the process. Tanaka explained that while in Japan, the Anti-Olympics movement merged all of these separate groups, whereas in Rio, “we focused a lot on the issue of the city.”

According to Tanaka, the Olympic model–replicating a set of international “standards” regardless of a region’s “specific condition”–is misguided. She described some of the most disruptive Olympic projects in Tokyo so far. This includes the National Stadium in Meiji Park, which is expected to cause gentrification in the surrounding working-class neighborhood, and has closed the park entirely (rather than the partial closure needed to construct the Olympic buildings), resulting in the removal of its homeless community. The demolition of the Kasumigaoka Apartments, due to intense pressure and forced removal of elderly residents, some of whom had already been evicted once for the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games, was also highlighted as an example of forced evictions for the Games. Given the similarity of the two cases, Vila Autódromo residents made a declaration in support of those resisting removal in the Kasumigoaka Apartments.

Tanaka noted how environmental justice issues had marked the preparation for the Olympics in Tokyo, just as they had in Rio. The government has planned to relocate the famous Tsujiki fish market, but the proposed site contains contaminated soil. Similarly, Ichimura added that recovery from the nuclear disaster in Fukushima was ongoing, while Olympics preparations have caused the government to shift their stance on “safe” levels of radiation.

Both Tanaka and Ichimura’s presentations highlighted that the promised post-Olympic benefits only reach a handful of people, and can actually harm the public good. For example, while hosting the Games is thought to increase investment and tourism, this activity only takes place in the specific city or region where the Olympics are held. Furthermore, with high-tech facilities to maintain after the Olympics, government funds are directed away from important public programs and into Olympic infrastructure even once the Games have ended. Similarly, while homeless people were most affected by the removals in future Olympic sites, Ichimura noted that this change from “public space into a completely private space” is a loss for “all people, not only [the] homeless.”

Ichimura’s presentation went into detail about resistance in Tokyo. Living in a homeless community as an artist at the time when many of the projects began, Ichimura began to organize with her Blue Tent Village community in Yoyogi Park. However, the Blue Tent Village was eventually removed, and the homeless community has all but disappeared from the neighborhood, given that most of the previously public spaces are now construction sites. “It’s difficult to find a place to sleep,” notes Ichimura. To elaborate on the theme of eviction, Ichimura recounted a story of an old woman who lived in the Kasumigaoka Apartments under the care of her daughter. The woman was sick and unable to move homes in her condition. She remained in the apartment in spite of the government’s “pushing” and insistence that the Games were part of “a national plan.” However, as a noisy demolition began on a complex nearby, the woman passed away. It is felt that the struggle to stay in her apartment was an important trigger.

To conclude, Tanaka and Ichimura spoke with each other and answered audience questions. When asked about similarities and differences in the two cases, Tanaka explained that the Japanese government has strict rules that regulate protests, while their protest police are unarmed. In contrast, Tanaka explains, while “we have more freedom to demonstrate here [in Rio],” the threat of police violence or retaliation is more intense.

Ichimura is planning for the future–“our movement is very small, but we can connect with another movement,” she affirmed. Activists hope that conversations like Monday’s continue so global groups can share strategies for how to combat and reduce the harm caused by the Olympic Games. As the world waits to hear which city will host 2024, with Los Angeles and Paris the only cities left in the running (all but Paris and Los Angeles have withdrawn their bids following public pressure), and Paris the only one without a visible protest movement, more and more observers are skeptical of the possibility for a positive physical imprint left by the brief event.