On Wednesday, May 31, the Brazilian Senate approved Provisional Measure 759/2016 (MP 759), which deals with land regularization for rural, urban and Amazonian lands. It now moves ahead for presidential approval. The measure faces harsh criticism from opposition in the Senate, mainly regarding the effect of the new legislation on rural areas, with claims that it will weaken small landholders and encourage the reconcentration of land and, at the very least, increase the rural exodus and pressure on urban areas. The MP, despite proposing innovations such as the direito a laje and the simplification of the processes of obtaining titles, is being questioned by social movements, who say that in practice it will make low-income households more subject to real estate speculation. A group of parliamentarians are now attempting to suspend the bill.

According to Rodrigo Numeriano, from the Ministry of Cities, the measure advances existing legislation by extending the scope of the “urban area” category to all those that exercise an urban function and launching a policy of land regularization beyond the mere concession of property titles. The law’s main novelty in terms of urban land regularization is the recognition of the so-called direito a laje, or “slab rights.” Property ownership in accordance with this provisional measure will no longer be linked to the land below; it may also be linked to the laje, or consolidated rooftop above. Thus, a property built on a laje becomes an independent unit, subject to taxation. And beyond the laje, any add-on the home, known as a puxadinho, can now be regularized as independent property, provided it has access to a public road.

“It’s the bending of civil law to reality,” says Numeriano, stressing how laws sometimes distance themselves from people’s real experience. Still, he says some lawyers have been bothered by the inclusion of the word “laje” in a formal legal mechanism because of its lack of “nobility.” They proposed a nomenclature that they argued to be more appropriate: surface and overhead rights. This illustrates well the institutional segregation and stigmatization, as well as the social and spatial segregation suffered by favela residents: a social reality, that can be theorized academically and can be the object of regulation, does not have sufficient dignity to be integrated into the law. It is linked to the criminalization of poverty.

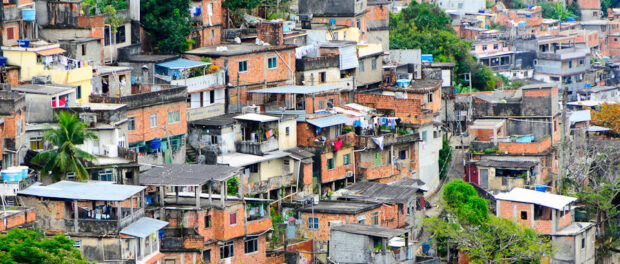

Another issue of nomenclature lies in the proposed change in the Provisional Measure to replace the old-fashioned term “informal settlements” with “consolidated informal urban nuclei.” This change, however, does not solve the essential problem of the term, contained in the term “informal,” which can be understood as denoting precariousness and transience, as if the favelas, in their diversity, did not have houses as formally built as any others, or weren’t as formal as any other part of the city.

In addition to the direito a laje, land regularization for low-income families will be free, donation taxes will not be required on land transferred from the federal government for social use, the adverse possession registry will automatically be converted into an ownership registry after the period defined in the law (five years for urban areas), and the notarial process to obtain titles will be simplified.

Another change may have an impact on social housing. Previously, when the government seized an abandoned property, it had little incentive to carry out structural improvements on said property and make it available as social housing, because within a three-year window the owner could go to court to reclaim it, along with the improvements that had been made. The provisional measure proposes that the owner only gets to reclaim the property if he reimburses the government for investments it has made in the property.

“The issue of regularization and formalization is not the political priority of most residents. Rather, the provision of services, the guarantee of rights (is the priority),” argues Rafael Soares, Professor of Social Work at Rio’s Pontifical Catholic University (PUC-Rio). “Buying, selling and renting has always existed in favelas, regularized or not.” For him, as long as land regularization emerges as a one-time program, and not a permanent and integrated policy, it will not produce good results.

Andreia, a doctoral student in Social Work and Cantagalo resident, sees land regularization as a threat. “In addition to raising living costs by collecting taxes, this means that if the person is unable to pay, the state will be able to come and take the person’s home. And it still paves the way for real estate speculation, for gentrification,” she said. According to analysts, public-private partnerships will be facilitated by this provisional measure and the regulation of high-end housing developments will be relaxed by the establishment of distinct regulatory mechanisms for low- and high-income homeowners, which is dangerous because it subordinates public services to market logic and pardons the speculative real estate market. “These areas still don’t have the socioeconomic conditions to dispute with market logic, a perverse logic within a neoliberal view that guarantees no rights. Families are going to suffer brutal capital pressure, they are less likely to maintain these lands,” says Maria Lúcia Pontes, from the Land and Housing Nucleus (NUTH) of the Public Defenders’ Office of the state of Rio de Janeiro.

“To give out property titles transfers the state’s problem to the individual,” says Soares, arguing that private property cannot be seen as the grand solution for land regularization. The causal relationship between periods of economic growth and real estate expansion and evictions, and between periods of recession and efforts toward regularization–which puts more land on the market and withdraws certain responsibilities from the state–is clear. For Soares, the bet should be made on social rent, combined with the infrastructure provision (such as transportation) and services (sanitation, security, garbage collection, among others).

Other criticisms of the provisional measure are in the weakening of Brazil’s pioneering Areas of Special Social Interest, or AEIS legislation. The MP extinguishes some of the criteria in this legislation that allowed favelas to be preferentially treated for upgrades by the government, while preserving qualities such as affordability. By facilitating the transfer of public lands to the private sector, the legislation threatens the fulfillment of land’s constitutionally-mandated social function and specifically threatens favelas located on public lands. In addition, the legislation does not contain the regulatory mechanisms for implementing that which it proposes. This lack of clarity leaves its propositions subject to future regulations, local laws and arbitrary actions by the government, weakening their application, different from previous legal mechanisms, which were self-applicable, meaning they contained in themselves all necessary regulation for their application.

An open letter against the provisional measure signed by various social movements and public institutions, including the NUTH, denounces these setbacks. It states that there is no urgency for the approval of this provisional measure due to the existence of previous laws governing housing and regularization, and that its publication on December 22 was suspect. New legislation is needed, but it is preferable to maintain older laws that have robust implementation guarantees while change is discussed in a participatory and integrated process.

Other planned changes in the provisional measure can be found on the Senate website.