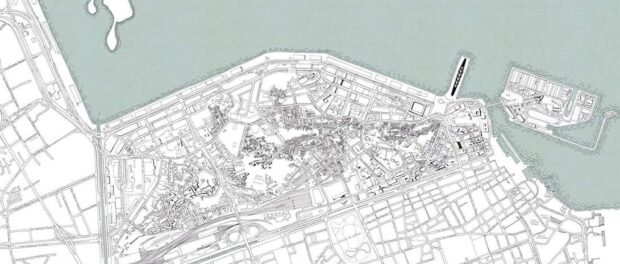

No urban district in Rio de Janeiro has changed more in the last five years than the Port Region. Not long ago, it was a heavily neglected area, with abandoned port warehouses and buildings resulting from a particular decay associated with lack of cooperation between sectors–much of the Port’s land belongs to the federal government, which for years was unwilling to free it up for development by the municipality. A large overhead expressway cut through and was partially responsible for the region’s particularly low air quality.

This impasse changed under the administration of Mayor Eduardo Paes (2010-2016) who partnered with the federal and state governments and used the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics deadlines as a tool to fast track infrastructure works and make the Port’s redevelopment his personal legacy priority. His Marvelous Port revitalization program spent more than R$8 billion and essentially transformed the area into a tourist attraction. The waterfront was made accessible once again, traffic was channeled underground into a three-mile tunnel and Rio’s first light rail transport system was introduced. A number of museums and attractions were opened, including the Rio Museum of Art (MAR), Museum of Tomorrow, and the city’s new aquarium, AquaRio.

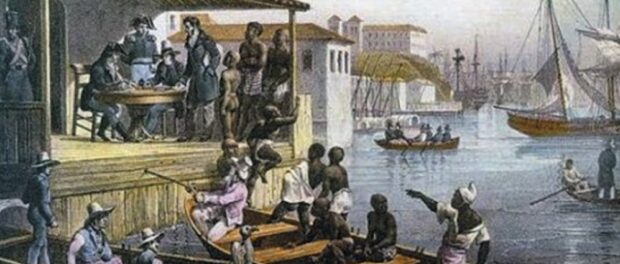

However, no level of cleaning to create the renovated Praça Mauá, snazzy Olympic Boulevard or shiny light rail can mask the history on top of which all of these developments sit. This same Port received the largest number of enslaved Africans in human history. And the remains of many of them are still there, literally and figuratively.

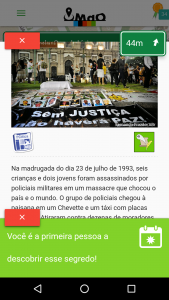

To make the deeper history of the Port as accessible to visitors as the ground-level interventions of recent years, Rio de Janeiro’s alternative journalism hub, Casa Pública, recently launched an app, for specific use in the Port area, called Museum of Yesterday.

Using Augmented Reality technology, facts and stories about the region no one can see at first glance become visible. The app mixes journalism, art, technology and a dash of “Pokémon Go” to bring to the public new insight into Rio’s Port Region. Like the title suggests, its focus is on the rich history of the neighborhood. But instead of capturing tiny monsters, the user unlocks stories while approaching them geographically by foot.

On your phone you can actually see where the Portuguese Royal family landed in 1808, where the Republic was proclaimed in 1889; where Princess Isabel signed the Golden Law in 1888, ending slavery, but also where the largest slave port of the Americas operated, before it ended. All these events are marked on a map from 1830. But there is also a current map marking incidents from the 20th and 21st centuries: for example, where President João Goulart held the rally at Rio’s Central Station, launching the military coup of 1964; a building that served as a torture center of the dictatorship which is today a police station; and even recent sites of nefarious nature, like where corruption took place currently being investigated in Operation Car Wash.

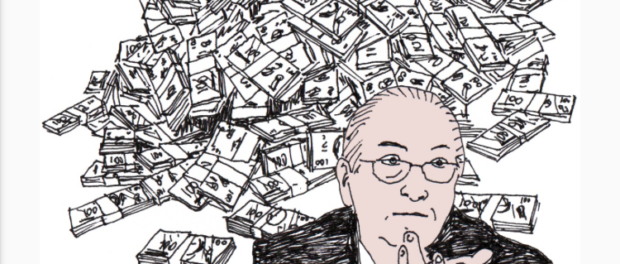

So when you are standing in Praça Mauá in front of the two-year-old Museum of Tomorrow, a drawing of Brazil’s former Congressional President Eduardo Cunha will appear on your display, telling you that “businesses which carried out the work for the famous Porto Maravilha had to pay R$52 million, or 1,5% of the total value of the public money invested for real estate development of the area (in bribes),” purportedly paid to Cunha, who is now in prison.

At Largo da Carioca another Operation Car Wash story pops up, even less known to the public: in 2012 a man walked around at this very spot with a suitcase carrying R$100,000, which was in fact bribe money. He was mugged and called the police. They got the robber who was arrested, whereas the man with the bribe money was not charged.

Both stories are part of a whole tour dedicated to corruption scandals, lasting more than one hour. Besides the Corruption Tour, there are four other specific ones: the Samba Tour starts at the first Candomblé terreiros and takes you to various famous samba schools; the Ghost Tour shares important and horrifying moments from Brazilian history which are rarely taught but which haunt the City Center to this day, such as the Candelária massacre; the History of Brazil Tour focuses on the most important historical events in the area; and the Terror Tour reveals terrifying stories from times of slavery and the dictatorship. It might not be by coincidence that the last one is unfortunately the longest.

Both stories are part of a whole tour dedicated to corruption scandals, lasting more than one hour. Besides the Corruption Tour, there are four other specific ones: the Samba Tour starts at the first Candomblé terreiros and takes you to various famous samba schools; the Ghost Tour shares important and horrifying moments from Brazilian history which are rarely taught but which haunt the City Center to this day, such as the Candelária massacre; the History of Brazil Tour focuses on the most important historical events in the area; and the Terror Tour reveals terrifying stories from times of slavery and the dictatorship. It might not be by coincidence that the last one is unfortunately the longest.

“In Brazil little value is placed on our historical past and there are also few tools to discover it,” says Mariana Simões, manager at Casa Pública. This lack of knowledge or appreciation applies even more to Brazil’s black history. During the construction works for the Porto Maravilha project more and more parts of this forgotten heritage showed up, the Valongo Wharf being the most famous one. The dock was the largest arrival point for enslaved Africans brought to Brazil–or anywhere. As of this week proponents of this history are celebrating its being awarded status as a UNESCO world heritage site. According to UNESCO it is “(…) the most important physical trace of the arrival of African slaves on the American continent. From a historic point of view, this is a testimony to one of the most brutal episodes in the history of humankind.” Despite its importance, the site is insufficiently cared for, with just a plaque explaining some basic facts. Which is at least more information than visitors get at other nearby places that are also part of the significant African history in this area.

The Museum of Yesterday app cannot change the invisibility inherent in insufficiently documented history, but it serves to make the site more visible, and supplies information that stimulates reflection. For Gabriele Roza of Casa Pública, who helped conduct research for the app, one of the most traumatic parts can be listened to at Praça dos Estivadores. Slaves were sold here as well. A voice reads out slave ads from a newspaper, people described as if merchandise.

Elsewhere on the tour, visitors learn that the famous Salt Stone, or Pedra do Sal, where salt was traded–and now home to a quilombo and made famous in recent years due to its hosting a weekly Monday night street samba party and other events–was actually three times in size.

Another story tells about the so-called tigers: “As the water table was not very deep, building cesspools was banned. The residents’ urine and feces, collected during the night, were transported in the morning to be thrown into the sea by slaves who carried great barrels of sewage on their backs. As they went on their way, some of the content of these barrels, full of ammonia and urea, would seep out onto their skin and over the course of time it would leave white stripes on the black skin of their backs. These slaves were therefore known as ‘tigers.’ As there was no sewage system, these ‘tigers’ carried on their activities in Rio de Janeiro until 1860.”

All in all, about 160 spots in Rio’s old Center are covered by the app. Users can also click to make a suggestion to have more places included. “For us, the Port area is like a fish bowl. It is a reflection of what Brazilian history is,” says Mariana. That is why Casa Pública does not intend to include other Rio neighborhoods. Rather, their goal is to expand the app’s reach, especially to students. They also work with alternative tour guides like Cosme Felippsen from Rio’s first favela, also in the Port Region: Providência. Cosme uses the app on his tours.

But even without further advertisement, Casa Pública is happy with the growing number of downloads: “We did not have a specific goal in mind… We (initially) hoped to get at least 1,000 downloads. We have long surpassed that number.” Over two thousand people have now downloaded the app, in just a month.

The idea itself came up one year ago at Casa Pública’s Innovation Lab. It was created by journalists working for Casa Pública in partnership with the Dutch developer Babak Fakhazadeh and features illustrations by São Paulo-based artist Juliana Russo and narrations by singer Anelis Assumpção. Also, historian Laurentinho Gomes permitted the use of content from his award-winning history book 1808. His contribution is one of the reasons that Casa Pública chose 1830 as the date for the historical map included in the app. “Also, we didn’t want to go so far back, that you wouldn’t recognize it anymore,” Mariana says.

Download the App here on Google Play. And here for the AppStore

Learn more about the Museum of Yesterday, in Portuguese:

Museu do Ontem from Agência Pública on Vimeo.