Even though four years have passed since former Governor Sérgio Cabral officially revoked Resolution 013, which gave Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) control over authorizing cultural, artistic, and sporting events in occupied favelas, favela residents still live in a reality of cultural control. On Thursday, July 7, favela residents from Manguinhos, Rocinha, Jacarezinho and City of God that take part in the Favelas Against Violence Movement and the Popular Movement of Favelas met with representatives from the Public Security Subsecretariat and the Culture Secretariat to debate the challenges that cultural organizations in favelas face.

“There is still an expressive determination by the Pacification Police Commander for the UPP to regulate favela spaces. They think they are the bosses of the favela,” said a resident of Manguinhos. “The police are playing the role of a judge, (arbitrarily) deciding what people can and can’t do. City Hall is the one who should be doing that. We do not want to be at the mercy of the police,” said another.

But City Hall itself has been making the operationalization of existing legal regulations toward cultural events difficult. As stated by Djefferson Amadeus, lawyer and researcher in Social Cooperation at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), the right to host events is guaranteed by municipal law 5429/2012, which says that event organizers only need to alert the local administrative region (RA) about the time and location of any cultural event in a public space by cultural groups.

One of the barriers to the operation of this law was instated by Rio de Janeiro’s new mayor Marcelo Crivella at the end of May, and is known as Decree 43.219/17. This decree establishes a commission linked to the mayor’s office that is tasked with approving any public event attended by more than 1,000 people. The commission can veto the event at any time before or even during its occurrence, even when event organizers have obtained the necessary licenses. In addition to bureaucratizing the process, this commission makes room for politicians to block events on the basis of political and ideological motivations. Soon after the decree, City Hall published Resolution 58, however, exempting religious celebrations from the law, even from attaining basic permits [it is important in this context to take note of the new mayor’s religious affiliations]. Up until the beginning of July Crivella was still enforcing a law that prescribed a fine of up to R$5000 for excessive noise in bars, parties and plazas.

“What bothers residents the most is the non-standardization of the rules. Some of the rules seem to only apply to favelas,” said one resident. “Let’s see if these laws will apply equally to church events as they do to baile funk dances,” she added.

“In addition to stall owners who will be out of work, the prohibition negatively impacts the income of residents who rent out their bathrooms during events. This without a doubt symbolizes the criminalization of favela culture,” said a resident. It is important to recognize these activities as employment and income generators inside the community, as well as their role in reinforcing community members’ self-esteem and providing leisure options.

In the Mandela 2 favela in Manguinhos, last year’s traditional Christmas festival did not happen because three days before the event the UPP commander declared it would be necessary to obtain licenses from the 21st Police Station, City Hall, and the Fire Department. The UPP spokesperson said the decision was made in accordance with “Resolution 013 of the Security Secretariat, jointly with Seseg/Sedec 134″—even though the first of these resolutions was repealed in 2014.

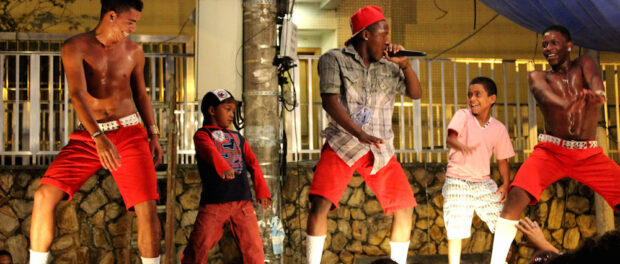

Today things in Manguinhos are a little better for residents. “The former UPP commander was inflexible and did not want to engage in dialogue. We had various meetings and they installed a new commander. He permitted a show and a dance last week in Mandela to satisfy the residents,” said a community resident. In this way, the organizers face obstacles and look for ways to circumvent them. One of the methods has been to rename funk music parties, traditionally called ‘baile funk,’ as ‘pagofunk,’ a rebranding which organizers claim has a higher chance of approval. This comes despite the funk genre having been recognized as cultural heritage by the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (Alerj) in 2009.

“The UPP says that it cannot authorize ‘baile’ dances because of security concerns and the risk of violence, but the police don’t appreciate or do anything about our daily security. They just sit there at the base of the community,” said another resident. Furthermore, even when authorization is granted, it is never guaranteed that a spontaneous police operation won’t suspend the activities.

“We are only asking for what is protected by law, including residents’ right to work, recreation, and income,” said a resident of Manguinhos. He reaffirmed his support for the July 7 meeting between residents and government to ensure that favela culture can develop without unjustified police interference. A proposal was introduced to send a Service Order to UPP and battalion commanders, demanding a procedure be adopted to ensure event authorization decisions are not made arbitrarily. The residents of Manguinhos also demanded that the Sub-Secretary of Security plan a plenary session or a visit in their community.