This is the second article in a four-part series on Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design.

When it comes to Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, one thing is clear–particularly with the city’s oldest favela turning 120 this month: government hasn’t provided adequate alternatives or properly attended to them in 120 years, and there is no sign of that policy letting up.

As communities that are a product of government neglect, favelas have always been and continue to be in charge of their own urban planning. Residents can’t wait for planners to show up and save the day when facing issues that require immediate, or even not-so-immediate, solutions. Furthermore, when it comes to preventing violence, experience shows that state intervention isn’t always what residents want or need.

Even so, planning and design principles to combat violence are generally seen as technical and inaccessible, seemingly only applicable by bureaucrats and police. Even techniques in Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED), described in the first article in this series, have become highly technical. In the context of safety, then, what can favela residents do to take control?

Introducing Tactical Urbanism

For the past several years, tactical urbanism, especially in the United States, has been a hot topic among urbanists and residents frustrated by the slow (or non-existent) delivery of government planning and maintenance services. Tactical urbanism is characterized by immediate, low-cost and fairly simple interventions that make a neighborhood or area more enjoyable, safer, or more efficient. The nature of these projects vary. Some are implemented by residents fed up with local government’s lack of action, while others are implemented by city governments as pilot projects or even stop-gap measures to appease residents.

It is this method—the quick and accessible method of tactical urbanism—that holds enormous promise to make the inaccessible, like CPTED, accessible and even change the way citizens engage and lead city planning. Although the concept of safety in tactical urbanism has been relegated to bike and pedestrian safety, by expanding its application to citizen security, tactical urbanism can support residents in leading planning and design efforts to create safer and more vibrant communities.

Tactical Urbanism in Favelas

Though favelas could be described as, at their essence, tactical urbanism for the provision of shelter, the term is more often applied in contexts of privilege. Ironically, in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, it was Favela Painting—a project led by two Dutch artists who raised over $100,000 to “paint an entire favela,”—that brought international attention to the potential for tactical urbanism to change the perceptions of a stigmatized area through a simple intervention, although the project itself was neither inexpensive nor community-driven.

Then, in 2014, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City showed an exhibit titled “Uneven Growth: Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities.” As the title suggests, it focused on tactical urbanism as the crux of urban transformation in six megacities, including Rio de Janeiro.

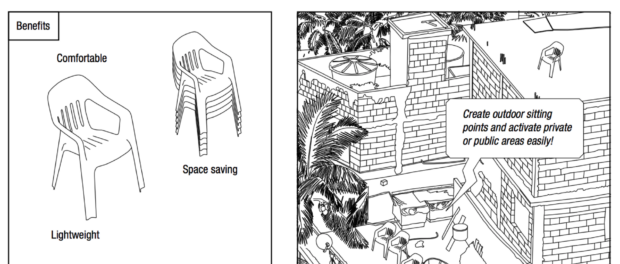

The showcase included a catalogue of how to turn everyday products into tools to activate public and private spaces in favelas. The products themselves are either rather obvious and already widely applied—the first intervention listed is using standard plastic chairs to provide seating in favelas—or impractical, as most of the materials listed are not easily accessible (you must buy the parts from a design school in Zürich). And the results are often of questionable utility.

The exhibit, particularly as it pertained to Rio de Janeiro, exposed the need for better analysis as well as deeper engagement with tactical strategies already being utilized by residents of favelas.

Critiquing and Transforming Tactical Urbanism

Tactical urbanism itself has not been immune from critiques, especially regarding the feasibility for people of color to leverage the tactic. Looking at successful cases of tactical urbanism can leave the impression that this is an art form reserved for wealthy, mostly white residents who are fed up with sub-par services from their local government and have the time, energy, and resources to take matters into their own hands. Furthermore, because implementing these strategies can mean breaking the law or at the very least violating some expected code of conduct, tactical urbanism brings to the fore spatial politics, or who can and can’t occupy space and partake in certain behaviors without being ousted or even criminalized.

In 2015, an interesting case in which those dynamics played out arose in the state of Minnesota in the United States. It centered around Nicollet Mall, an outdoor shopping and dining district in downtown Minneapolis. There, JXTA, a local non-profit specializing in tactical urbanism, was hired to enhance place-making at the mall, an opportunity they leveraged to create spaces not only for patrons of the area, but for black and brown youth and the homeless population. They created public spaces of engagement for residents through art-making, bubbles, and games and asked residents for feedback on different aspects of urban spaces. JXTA made black spatial politics an explicit part of their work and sought to normalize the presence of stigmatized populations through these tactical interventions. As part of their work, they also advocated for the repeal of local “lurking and spitting” ordinances that legally justified racial profiling in the area.

What made JXTA’s work unique was their creation of new spaces for interaction among diverse groups which as a consequence empowered marginalized groups to engage the local government for more permanent change by focusing on issues of safety. They sought to destigmatize and decriminalize populations of youth and adults who were often pushed out of spaces under the assumption that they were a danger to the public, and they challenged who could and could not occupy those spaces.

Marrying Tactical Urbanism and CPTED

Elsewhere, in Santa Cruz, California, residents of Lower Ocean Street formed an informal neighborhood group to address safety issues in the area. Using CPTED principles, they painted over graffiti, cleared the streets of litter, and set up activities for children. They also became advocates and reached out to local government for the installation of street lights, the opening of a new park, and the closing of a bar with ties to organized crime. Lower Ocean Street experienced a 70% decline in its crime rate over the three years after the neighborhood group was formed.

This discussion builds to the potential of merging tactical urbanism and CPTED. By using small-scale, low-cost, and short-term interventions, local residents can be empowered to address immediate community needs while also changing the perception of spaces and the people who occupy them. These strategies are especially relevant to the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, where municipal services have chronically underserved communities and where spatial dynamics and stigma continue to preclude the safety and social and economic mobility of residents.

Without a doubt, tactical urbanism has been present in Rio’s favelas from day one, even if it was never labeled as such. Parts three and four of this series will look at examples in Babilônia and Asa Branca, respectively. By explicitly incorporating the empowerment of residents and taking into account democracy and social justice, citizen-led planning in the form of tactical CPTED has the potential to create new pathways to urban safety, growth, and evolution.

This is the second article in a four-part series on CPTED.

Mayu Takeda is studying for her Master’s in Urban Planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.