On Friday, October 20, the graduate economics program at Rio de Janeiro’s Fluminense Federal University (UFF) continued a series of events celebrating its 30 years of existence with a debate on the topic of community waste management. The debate was moderated by economist Roldán Muradian (UFF) and featured Italian political ecology professor Giacomo D’Alisa (from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain), Pontifical Catholic University (PUC-RIO) professor Rafael Soares, Pavão-Pavãozinho resident and Favela + Limpa program director Leandro Abrantes, and UFF economics graduate student Teresa Meira.

Roldán Muradian explained that in a time of crisis both for the State of Rio and for Brazil, the event organizers decided that they “didn’t want to talk about the crisis, but about responses to the crisis. For this reason we called different people working with creative community solutions.”

By drawing on his work on the political ecology of waste in Naples, Italy, Giacomo D’Alisa highlighted two key messages: first, the problem of waste is not the simple presence of trash in the streets, but stems instead from much deeper institutionalized complexities; second, civil society organizations are essential for developing solutions when large institutions are part of the problem. Drawing on alarming data on waste management around the world, D’Alisa showed that the problem is not unique to certain urban centers, arguing that we need to abandon the idea that waste problems are tied to particular local cultures. He noted that São Paulo residents often think of people from Rio as lazy, but such a stereotype becomes an explanation and justification for the waste crisis. He underlined that “the problem [of waste management] is structural. It materializes in particular situations due to conditions of power, not because of cultural conditions of marginality.”

As an example, D’Alisa gave an overview of Naples’ waste management crisis, which he said is sustained by cooperation between governing institutions and corporations—which produce large quantities of trash—and organized crime. In this context, crucial civil society activism has been growing, exemplified by a movement called Stop Biocidio. Stop Biocidio has successfully fought for environmental crimes to be recognized as penal crimes, for epidemiological research in regions affected by toxic waste which have proven the correlation between rising cancer-related deaths and mismanagement of trash, and for the prosecution of the companies found to be connected to illegal waste management processes.

The second speaker was Rafael Soares, who presented his research on the democratization of access to public services in favelas. He first outlined the problematic trend in academic, media, and public discourses that view favelas as “something different and not part of the city.” For him, this view of favelas as ‘the other’ or divided from the formal city is a “simplification of the complexity of the heterogeneity of society.” These discourses, he argued, often focus on illegality or suggest that favela residents don’t pay taxes, and this impacts the priorities of government upgrading projects in favelas, which focus on legalizing services.

What I would like to introduce,” Soares said, “is a reflection more on the politics of formality.” Water and electricity services, for example, are often treated as signals of formality. Soares stated that because the government often sees favelas as illegal, it doesn’t intervene to connect the communities to water services in an apparent effort to maintain the communities’ precariousness, forcing residents to obtain water or electricity themselves through other means. This, in turn, reinforces the stereotype of illegality surrounding favelas. However, he explained that when the government does intervene to formalize services in a favela, it usually ignores existing community initiatives in these areas and fails to understand residents’ financial limitations. Now that the public electricity utility Light has formally connected many favelas to the city’s general electric grid, some residents are not able to pay for the overly expensive service. As such, Soares concluded with the question of whether the government is really trying to guarantee access to services or not.

Next, Leandro Abrantes from the Pavão-Pavãozinho favelas between Rio’s famous Ipanema and Copacabana beaches, shared the story of his own path to founding the recycling program Favela + Limpa (Cleaner Favela). The son of a baker, his life was turned upside down when his father was killed. After a time living on the street, Abrantes moved to Pavão-Pavãozinho where he managed to open several bakeries and restart his life. One day he saw a news report that called his new home the “most dirty favela of Rio de Janeiro” which, he explained, stirred his desire to do something for his community. He and a friend started to visit different communities where projects were already tackling trash collection and recycling in order to learn from them and create a network of people working on community sanitation. He believes community knowledge is essential, explaining:

“When the State comes [to favelas] it wants to do what it wants… But I don’t believe in this… I think that if you take a leader of the community who understands everything, this person will show you all the possibilities of what can be realized and what can’t be done. But no, [outsiders with PhDs] think that having studied this problem for many years outside [the favela] they will have the solution. But I say this: all problems have a solution that comes from the inside [of the favela].”

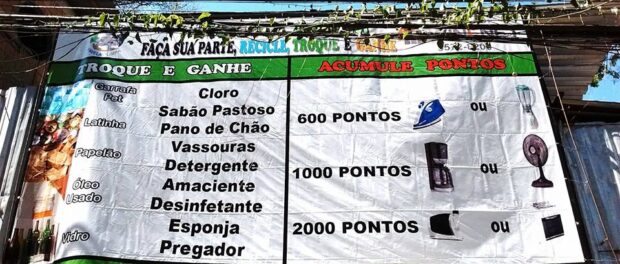

Favela + Limpa coordinates and incentivizes local recycling as a means of generating “jobs, income, health and quality of life” for the neighborhood and advancing environmental education. Abrantes recounted how his own work has involved cleaning the neighborhood’s streets, writing songs with lyrics promoting environmental messages, putting posters on community walls, and coming up with many different ideas to involve the community in questions of sanitation. He admitted that his project has faced challenges, but he can see that his neighbors appreciate his work. He concluded with the declaration that it is important to keep pursuing dreams in a space where the government has left little space for dreaming.

The last speaker, Teresa Meira, discussed her thesis research on “economic incentives and recycling in the favelas.” After first acknowledging the importance of community cooperation and local knowledge in developing her research project, Meira outlined the Light Recicla program, which is an initiative of the public electric utility to incentivize recycling. The program allows residents of low-income communities to bring recyclable waste to a nearby “eco point” in exchange for a discount on their electricity bill. However, Meira’s findings show that participation in the program remains low, as many residents prefer to cooperate with local recycling initiatives instead. She suggested that a lack of information, the program’s inconvenient timetable, rising violence across the city, and the fact that the discount Light offers is lower than market prices for recyclable materials are all factors that make it unlikely for residents to participate. Despite the low participation rate, Meira pointed out a particularly interesting data point: 5% of participants in Light Recicla decided to devolve their discount to community-led organizations, which in her opinion shows a great level of social cohesion.