This is the third article in a four-part series on Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design.

“First of all, this plaza is different because this plaza is our plaza,” declares André Constantine, a powerful speaker with a booming voice and the president of the Residents’ Association of Morro da Babilônia, a South Zone favela abutting the upscale neighborhood of Leme in Rio de Janeiro.

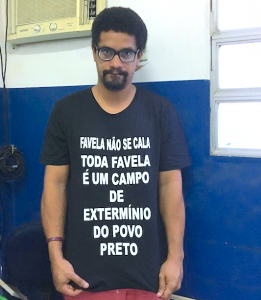

A self-described “militant politician,” Constantine is wearing a shirt that reads: “The favela is not silent. Every favela is an extermination camp for black people.” He is leading a community profoundly impacted by gentrification and—since the unraveling of the public security pacification program—the return of violence, and he is explicit about the racial justice lens of his work. Faced with limited support from a city government confronting an economic crisis, escalating territorial disputes between two rival gangs, the continued occupation by Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), and a host of other issues to address, Constantine has responded with creative solutions. And as part of his efforts to reduce violence, he is implementing principles of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED), although he doesn’t call it that.

“Obviously, the creation of shared and public space is linked to public safety, just like in the rest of the city. Lights will prevent crime. This is all obvious,” Constantine explains. To him, these are not esoteric concepts; they are facts that he has seen tested and verified in his experience as a favela resident and leader.

Constantine and the Residents’ Association are in the process of implementing the Semente Viva (Living Seed) plaza, a pilot project he hopes to replicate in other areas across Babilônia. The idea is to create public squares that, besides providing spaces for leisure and interaction for residents, will create safer areas with better lighting and more eyes on the streets. The Semente Viva plaza will serve as the prototype, and it is an example of how an obscure and often-inaccessible concept like CPTED is organically being implemented in community-led projects.

Residents’ need to address public security stems from a lack of appropriate government action. Comparing the war on drugs in Brazil and the United States, he observes, “And here too we have a political genocide against black people. The policy of the war on drugs is a policy of war against black people and poor people.” He points to the case of Rafael Braga, a young black homeless man jailed for carrying cleaning products during Brazil’s 2013 mass protests, whom many believe was framed by the police. “The UPP isn’t about public security,” he concludes.

Residents’ need to address public security stems from a lack of appropriate government action. Comparing the war on drugs in Brazil and the United States, he observes, “And here too we have a political genocide against black people. The policy of the war on drugs is a policy of war against black people and poor people.” He points to the case of Rafael Braga, a young black homeless man jailed for carrying cleaning products during Brazil’s 2013 mass protests, whom many believe was framed by the police. “The UPP isn’t about public security,” he concludes.

The establishment of the Semente Viva plaza will rely on the indigenous Brazilian and favela tradition of collective action, or mutirão. Constantine explains, “We don’t wait around for the State. We do things for ourselves. It’s just a continuation of what was done by the first inhabitants.”

Projects in Babilônia are often about resident leadership and partnerships with external parties. The Residents’ Association has proactively reached out to the neighboring formal neighborhood of Leme to tackle joint problems, including crime and trash. “The problems that exist in the favela will affect the formal areas of the city,” Constantine says. “The trash that is produced here doesn’t climb the hill. It goes down. All of the trash, all of the sewage produced here, it goes down and affects the formal areas of the city. We need to understand that a problem for the favela is a problem for the city.” To tackle these common problems, one of the aims of the Residents’ Association of Babilônia is to integrate the favela into the formal neighborhood of Leme.

If successful, the Semente Viva plaza will be the result of multiple partnerships with private companies and even the cash-strapped city government. The Residents’ Association is working with a local landscape architecture firm, EMBYÁ, to design the space, and also enlisted the help of a cleaning service to clear the surrounding area of household appliances dumped there. Constantine sees the productive partnership with EMBYÁ as a victory in itself, noting how researchers interested in favelas often come to Babilônia but do not provide concrete returns for residents. “We became annoyed because they always want to research black people and the favela. And we don’t see concrete returns on this research, and so we feel like rats in a laboratory.”

Physically, the plaza will be equipped with amenities such as enhanced lighting; fixed drainage and guard rails; a playground with rubber floors, a slide, and a trampoline; a fold-up table for barbecues; bleachers; and even trees originating from Africa. The trees are a nod to the ancestral roots of many of the residents, and their inclusion aims to enhance locals’ sense of ownership over the plaza.

“Without a doubt, when the plaza is done, we will directly solve the problem of garbage because no one will want their plaza of this quality to be next to trash,” Constantine asserts. But for this to happen, the project must be led by residents. “This is very important, that it’s not a top-down project. The public sector has brought many projects that were top-down,” he adds, pointing out the cluster of plazas built by the City concentrated near the entrance to Babilônia. “Resident participation in the planning process must be a minimal requirement when they’re going to receive some urbanistic intervention. It’s really bad for the sense of ownership and belonging of the space, regardless of the project, when residents aren’t consulted… If they don’t participate, they won’t feel like it’s their space and the space will become degraded.” Constantine knows that with a sense of ownership comes better maintenance and community-policing of the space, followed by enhanced safety and security.

But the plaza alone will not be enough; it is only one of many tools to combat violence. Advances need to be made on social issues, and for Constantine, the principal question is around the problem of racism in Brazil. “The violence practiced by the State isn’t just police brutality,” he says. “It is symbolic violence. The lack of schools, of health, these are more lethal forms of violence.” He sees investment in education as the key issue for low-income, black Brazilians.

This is the third article in a four-part series on CPTED.

Mayu Takeda is studying for her Master’s in Urban Planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.