For many years the great actor Chico Anysio made us laugh through his character “Jovem,” whose nickname—meaning “youth” in Portuguese—was shortened from Jovelino Venceslau dos Santos. Jovem was based on another character played by the actor Taumaturgo Ferreira in the soap opera Mandala, which aired on Globo TV in 1987. Although he was a young white middle-class surfer from Rio, it was interesting to observe the character’s embodiment of the dominant stereotypes of what it meant to be young in Brazilian society.

In practice, the term “youth” is still very new and is contested in both academic and political spheres, as it is worldwide. As a result, there is a wide range of cut-off ages for youth around the world. For instance, in Brazil, some would suggest that youth includes those between the ages of 15 and 24, while others expand this number to include those aged 15-29. In Japan, people aged 15-35 are considered youth. Not bad, right? In the 1980s in Brazil, questions of what it meant to be young were under the spotlight with the “Se liga 16” (Get Connected 16) campaign, which resulted in the members of the National Assembly of 1988 granting voting rights to Brazilians aged 16-18. At the same time, they opted not to lower the age of criminal responsibility (from 18) and moved to prohibit those under 18 years old from driving, smoking, drinking, and marrying without the consent of a parent or guardian. The same assembly created the ECA, the Child and Adolescent Statute, which was considered one of the most progressive statutes of its time.

That being said, opposition groups never accepted these achievements and are still trying today to eliminate these rights. Even ECA, which was never implemented fully in practice, is under threat. As a result, in 2016 Brazil dropped 64 places in the ranking of the Kids Rights Index—a watchdog organization that monitors children’s rights around the world—from 43rd position to 107th. This is on top of the alarming rates of child labor and 17.3 million youth living in poverty (or extreme poverty, in the north and northeast), according to data from the Fundação Abrinq which compared the realities of children in Brazil with the goals the country signed on to as part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

These data only reinforce research on youth mortality in Brazil, which reveals the particular dangers confronting black youth. Data from the 2017 Atlas of Violence show conclusively that in the last ten years black youth mortality rates increased 18.2% while rates for their non-black counterparts decreased 12.2%. Such disparities leave no doubt that a project to exterminate poor, black youth is underway in this country.

Many of these numbers are already well known, but it is important to reinforce them. However, I would like to contribute to this discussion in a different way. I would like to use the remaining space to discuss what it is to be young, especially in the favela. To share with you all what the statistics about poverty and violence conceal about this group. Some may think that by doing this, we’re contributing to a process of obscuring the daily crimes committed against favela youth. On the contrary, I want to illustrate what is lost with each death of a young person from the favela. I am fascinated by the capacity of these youngsters to reinvent happiness and how, in the midst of such adverse conditions, they are able to go on with their “lives in the saddle of these pains.”

In the early 2000s, I was invited by the Casa da Mulher Trabalhadora (Working Women’s House), Ibase (the Brazilian Institute of Social and Economic Analysis), the Bento Rubião Foundation, the Youth Observatory (at the Fluminense Federal University—UFF), and CEDAPS (Center for Health Promotion), among others, to create a youth network in the city of Rio de Janeiro. This experience was so important to me that I invited my friends to create a similar network in Maré: the Rede de Jovens da Maré – Jovens Sem Complexo. I was very impressed with the force that we built in that time. I have accompanied the networks’ ongoing activities ever since and I feel as if I have the task to be a chronicler of the movement.

To think of the dynamism of youth alongside the favela’s political, social, economic, and cultural dynamism is a significant challenge. Merely recognizing young peoples’ potential is not enough. My personal mission is to broaden perceptions about this group and I hope I can encourage others to join me on this journey. I am still not convinced that “youth” is best described as an (arbitrary) age range, between 15 and 29, because I think it’s really difficult to claim that young people from such distinct places, such as those across Brazil, are the same due to their age. Because, what does it mean to be young for someone, like me, who began to work at age nine and only started my university education when I was 29, in contrast to my peers at the university who were 17 years old, had already traveled to Europe, spoke two foreign languages, and only planned to start working after completing their Master’s degrees?

In this sense, everything that I write here carries the idea of youth as the unfinished, of freedom, of independence, a combination of growth without worry, of happiness and sadness alongside apathy, of the natural alongside the supernatural, of pain alongside pleasure, and of the curiosity to learn new things with the understanding that this will not always be possible. My commitment is what makes me feel alive, as this is the characteristic of youth that I find most seductive. As for the concern with what it means to be young, I would prefer to think of it this way: to be young is the “pain and pleasure of being oneself,” because as Chico Anysio’s character used to say, “youth is attitude, youth is transformation,” “youth is something else, gosh, Mom.”

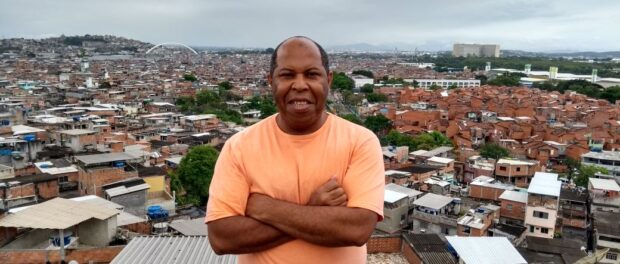

This article was written by Lourenço Cezar and produced in partnership between RioOnWatch and Fala Manguinhos! (Speak Up Manguinhos!). Lourenço has lived in Complexo da Maré for 40 years. He is currently pursuing a Master’s degree at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). He is also the coordinator of the Department of Geography and Environment for the Duque de Caxias College, and a director of Maré’s Center for Solidarity Studies and Actions (CEASM) and the Museu da Maré.

As a community communication initiative produced by and for Manguinhos, Fala Manguinhos! was set up to defend human and environmental rights, and to promote citizenship and health with the direct participation of residents in the decisions that involve the Community Communication Agency of Manguinhos, from the meetings of the communication group and the Community Council. Follow Fala Manguinhos on Facebook here.