While Rio’s oldest favela, Providência, marks 120 years since its founding, the city has been undergoing a broader moment of historical reckoning, considering how best to utilize the past in order to construct identities and face the future. As the establishment of the Evictions Museum in Vila Autódromo and the struggle of the New Blacks Institute in the Port Zone show, collective engagements with history often occur through museums, as public spaces dedicated to the past. In particular, museums can serve as spaces for marginalized groups like favela residents and Afro-Brazilians to claim and share their stories, a crucial ability given those communities still face violence and societal obstacles today.

The City government under new mayor Marcelo Crivella described its intention to play a role in remembering Rio’s history earlier this year when it announced a plan to create a Slavery and Freedom Museum (Museu da Escravidão e da Liberdade, or MEL) in Rio’s Port Zone. The museum, already scheduled to open in 2020, would memorialize Rio’s past as the largest slave port in world history and also detail elements of the Afro-Brazilian experience after emancipation, including samba and other cultural expressions. In response to this plan, though, many members of Rio’s historical community and representatives of the numerous community-based museums and historical projects that already exist in the city have expressed doubts about the efficacy and intentions of the proposal.

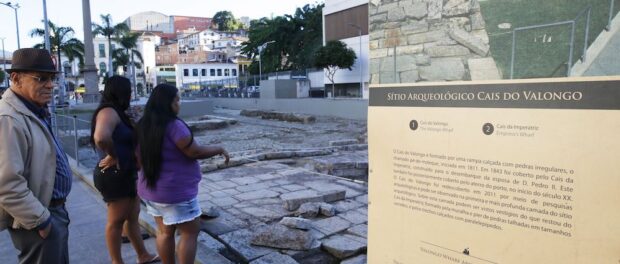

Part of the criticism of the MEL is logistical. The current plan is to house the museum in a nineteenth-century warehouse built by André Rebouças, an engineer and one of the most prominent Afro-Brazilians in Rio’s history, adjacent to the Valongo Wharf in the Port Zone. The wharf, which was the hub of Rio’s slave market and the site of innumerable transactions of human beings, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in July, yet remains largely unvisited, with no permanent security.

While many commentators agree that the MEL’s proposed location next to Valongo is a logical choice, the warehouse in question is already occupied by Ação da Cidadania (Citizen Action), an NGO that works to combat inequality and which was established in 1993 by a highly respected hunger activist, the late Betinho de Souza. Roberto “Kiko” Afonso, the NGO’s current Executive Director, detailed a frustrating “lack of respect” when dealing with the City, revealing that Ação da Cidadania was not even informed directly about the plan for the MEL, even though the NGO has invested more than R$15 million in the building since rescuing it from dilapidation twenty-five years ago. In a Facebook comment made on June 30, the municipal Secretary of Culture, Nilcemar Nogueira, stated that the NGO would continue to operate “in the same place.” Afonso, though, spoke of numerous “false narratives” from the City, and pointed out: “We have 6,500 square meters at the moment. All our future programs were designed to fit our space.”

Another criticism of the museum is financial—while flashy Olympics-era projects like the Museum of Tomorrow ran far over budget and continue receiving public support, community-based institutions like the New Blacks Institute (IPN), the Americas’ largest slave cemetery next door in Gamboa, have had funding cut off, with the result that the IPN has been struggling for months just to keep its doors open to the public.

Coming in the midst of Rio’s financial crisis—which has been used as a justification for the drying-up of funds for the IPN and other sites—the announcement of a massive new construction project in the Port Zone is baffling to many. Afonso lamented: “Why come up with a new museum now? It is just about political and personal benefit. What is the logic for this?”

The North American historian and long-term Rio resident who runs the Afro-Rio Walking Tour, Sadakne Baroudi elaborated on this point: “If in the US we have a problem with the military industrial complex, in Brazil we have a construction complex” that allows for large-scale corruption. “If we have two million for a new museum, then all the pigs can come to the trough.” Baroudi and others, in fact, expressed doubts that the planned museum will ever even see the light of day.

More broadly, though, Baroudi argued that “gentrification projects” like those occurring all over Rio’s Port “are whitening projects. They are anti-Black projects… So it is a way of kind of corralling and controlling the black African story” on the part of the City’s largely white government. Indeed, two dominant themes among critics of the museum project are its lack of transparency and an apparent lack of participation by black Brazilians. In many respects, the plan for the MEL is woefully unequipped to address a particularly painful piece of Brazilian history, all while residents of the historic Port Zone face increasing pressure from gentrification and existing institutions receive little to no support.

The plan for the MEL seems particularly tone-deaf when placed in a citywide context. Rio is currently a hotbed of thought about so-called “new” or “social museology,” which emphasizes intimate, interactive experiences at museums that put visitors in contact with first-hand perspectives and subaltern narratives. This strain of museum—exemplified by many sites in the city—tends to lend itself better to the history of marginalized groups, as they grapple with historic realities that continue to affect nearly every aspect of their lives today. The MEL, though, appears to fall into a more traditional mold of museum, one in which the published narrative is more dominated by elites. “Brazil is a racist country and a museum of Crivella’s would be racist as well,” argued Heloisa Helena Costa Aberto, a Candomblé practitioner who was evicted from her home in Vila Autódromo before the Olympics. “Crivella doesn’t value black culture,” she explained. “He cut off budgets from Carnival, he forbade the samba at Pedra do Sal, he is against the Feira das Yabas. These are all black festivities. When the Valongo Wharf was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, he didn’t make a declaration or celebrate. He speaks with pride about his time in Africa [as a missionary], which is his way to establish a positive relationship with black people, but at the same time he wants to evangelize.”

One prominent Afro-Brazilian involved in the MEL is the project’s head, Nilcemar Nogueira, Crivella’s current Secretary of Culture. The granddaughter of one of the founders of the famous samba school in Mangueira, Nogueira served as Mangueira’s Carnival director and established the Samba Museum in 2015. She became Secretary of Culture early this year and last month hosted an energetic hearing and panel about the MEL that featured members of the Port Zone’s Afro-Brazilian community and representatives of the Pedra do Sal Quilombo and the New Blacks Institute. Though Nogueira introduced herself as a “militant” at the hearing and promised that the MEL would be part of the new museology movement, critics worry that she is a well-meaning figurehead put in place by superiors ready to overrule her, as occurred with Rio’s African Heritage Circuit under the City’s previous mayor Eduardo Paes. As Rolf de Souza, a professor at the Federal Fluminense University (UFF) and member of Rio’s black movement, put it, “this is a new strategy. Putting a black person there to divide the community, one fighting against another. So that we lose our common focus and fight her. Divide to govern.”

The MEL has received a certain amount of support and input from at least one of Rio’s community museums. The Black Museum, housed inside the Church of Our Lady of Rosário, a historically black Catholic church in downtown Rio, has participated enthusiastically in the working group put together to advise on the MEL. For Ricardo Passos, one of the museum’s directors, the MEL’s success in telling the black story “before, during, and after” slavery hinges on the participation of the institutions already dedicated to telling that story in the city. He is optimistic that an institution like the MEL will be able to bring together more of these sites in Rio than are currently in communication. The Black Museum, for example, is not part of the African Heritage Circuit that includes, among others, the New Blacks Cemetery and the Valongo Wharf. Passos envisions elevating the history of black Brazilians from the “regional” to the “global” level through the creation of the MEL and sees it anchoring an exchange of ideas and artifacts between smaller institutions.

Nor is there a general opposition to the idea of a museum like the MEL in Rio at all. Several observers emphasized that there is a need for more public discussion about the city’s slave history, but cautioned that any museum or similar site should not focus only or even primarily on slavery, as the MEL appears to do. “It shouldn’t be museum of slavery, but of the diaspora,” Souza said. A museum of “slavery and freedom” would be “a sweetened name,” according to Heloisa Helena, which white bureaucrats could hide behind in order to peddle a whitewashed narrative. As Souza stressed, “We have to be very attentive so that the museum is not erected in terms of white supremacist ideology. They want to show the so-called ‘soft slavery’—the idea that it wasn’t that bad and violent after all, in the end we all became friends. That the Portuguese were nice people, because in the end they mixed with slaves—this kind of idea.”

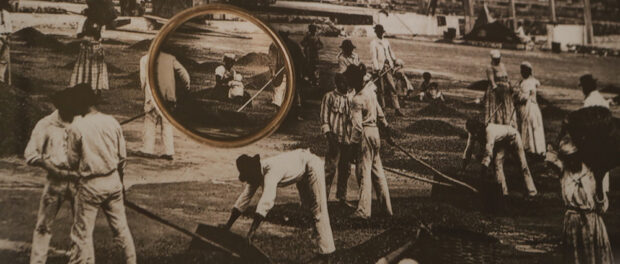

A museum of the diaspora would have to have in its scope the whole of the black experience in Brazil, including the rich culture—and struggle—still alive both in the Port Zone and in favelas today. As Baroudi pointed out, “when we look at the Port Zone, what we have is a living Brazilian African museum. I mean, this is an inhabited African black neighborhood for hundreds of years. Little Africa goes back to 1640.” Transforming this lived, fresh, and real experience into a territorial museum poses a host of its own challenges, but—as opposed to simply tacking a celebratory narrative of samba and the achievements of individual Afro-Brazilians like Rebouças onto the end of the story of slavery—that effort seems to promise a far more impactful experience for visitors than the proposed MEL does.

The City is not lacking in plans for this kind of memorial, however. The development of the African Heritage Circuit in 2011 produced a full plan for an as yet unrealized memorial that “contextualized slavery in a long-term way,” according to Sara Zewde, the Ethiopian-American urban planner who designed it, by linking several public spaces within Little Africa. Rather than just imagery of “whips and chains,” the full plan for the circuit incorporates elements of Little Africa’s material culture—elements like water, red brick, and ficus trees bringing African folklore and beliefs into a Brazilian setting—and integrates the circuit into the everyday lives of residents by creating places for meeting and recreation. Zewde said that she envisioned a museum as an “anchor” or “epicenter” to the circuit, suggesting that a museum in the MEL’s proposed location could fulfill one of Rio’s major needs if carried out in a way that answers the criticisms already raised and is tied to a full territorial memorialization of the area.

Zewde stressed that the City would not have to look far for ideas created with the black community’s perspective in mind: the Circuit represents one existing plan. And as the outpouring of voices about the museum makes clear, Rio possesses both the demand for an African museum and the people and energy necessary to make it an institution on the cutting edge of commemorations of the African diaspora worldwide.