The recent reconfiguration of Rio de Janeiro into an Olympic city directly compromised its inhabitants’ housing rights through the forced removals of low-income residents who lived in areas subject to real estate speculation, such as the Port Region, the South Zone, and Barra da Tijuca. These removals, ordered by decree during the administration of Mayor Eduardo Paes, represented flagrant violations of human rights as city representatives acted aggressively, threatened to demolish houses with residents and their belongings inside them, and forced people to sign legal documentation to allow demolitions by threatening that they would not receive compensation otherwise—all this without any dialogue or transparency.

Urban restructuring in the pre-Olympic years

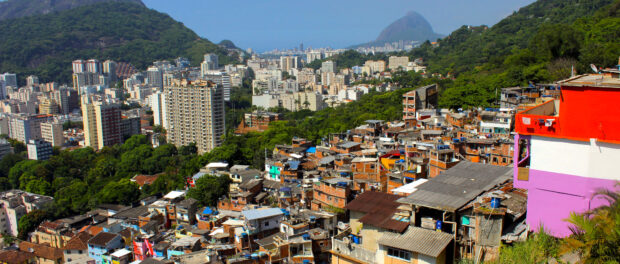

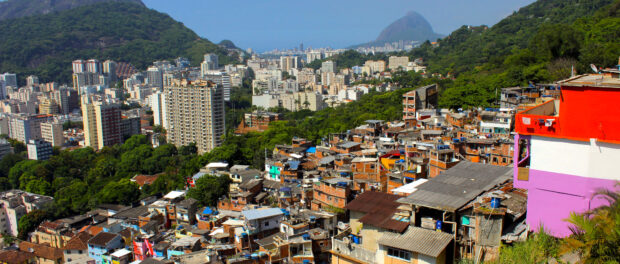

Rio’s urban restructuring was based on a project in which corporate logic prevailed in the development of public policies (the so-called neoliberal urban entrepreneurship), using removals as a political mechanism to allow real estate speculation. That is, it brought about the elitization of urban centers in order to promote the commercialization of the city and urban life, producing a corporate city, to the detriment of the well-being and rights of the impoverished population.

The official discourse justified the removal of homes for the realization of infrastructure works, such as the construction of Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems, light rail (VLT), and parking lots. It also justified removals through the indiscriminate use of the notion of environmental risk. These transformations were legitimized by the mega-events discourse of a purported legacy for the city’s population. However, it is possible to infer that such urban transformations would have happened independently of the Games because they are linked to an international project to develop capitalist cities that transfer money from public coffers to benefit big companies, maintaining the privileges of the rich and denying rights to the impoverished. In short, the Olympic City underwent a process of camouflage to hide its impoverished inhabitants, as more than 77,000 people were forcibly removed to areas further away from urban centers. The City used the removals to meet business interests, as well as to serve an elite marketing campaign aimed at tourists.

In fact, urban interventions in Rio de Janeiro advanced spatial exclusion and worsened social inequality by means of urban plundering and reallocating the impoverished population to more peripheral areas, far from their original homes and without public services or infrastructure. It is important to analyze segregation not only from a socioeconomic point of view, but also by paying attention to race and gender, considering that the affected favelas are mostly occupied by dark-skinned people and have large numbers of families headed by women. It is black women who have been most affected by the expropriation of rights and the social impacts of removals, since society has historically been based on slavery, private property, and patriarchy.

The emergency and resistance of Laboriaux

In this context, popular movements emerged to fight the policy of evictions and mobilized for the right to adequate housing and for the right to the city. The residents of Laboriaux formed one of these movements. Located at the top of Rocinha, Rio’s largest favela, Laboriaux was threatened with total removal on the basis that it was in an environmental “risk area” and prone to collapse, a common indiscriminate discourse in the context of the mega-events.

The following outlines the history of occupation in Laboriaux and how residents organized and developed practices for the permanence of families in the area.

In the early 1980s, the residents of Rocinha mobilized to protest forced removals and to demand basic sanitation and urban interventions for decent housing, especially for families suffering from floods. For this reason, the City government at the time encouraged occupancy in Laboriaux through the resettlement of 73 families in housing units, issued title deeds, and built a nursery and a school at the site.

Over the years, with the growth of the occupation and residents’ demands for secure land rights, the Bento Rubião Foundation began a process of land regularization throughout the Laboriaux area under the federal government’s Papel Passado Program. As such, by 2010 about 500 families out of a total of 800 had completed the process of regularization and were only waiting for the City to issue their land titles. However, in April of that year, torrential rains caused landslides and the death of two women in Laboriaux, leaving residents dismayed.

This tragedy was used by the City as an excuse to stop the land regularization process and to cordon off the area, threatening to remove all its homes immediately under the indiscriminate discourse of “area of imminent risk.” In addition, the City sealed off the the whole community of Laboriaux and marked its houses for removal with the acronym SMH (Municipal Housing Secretariat) without presenting a technical report confirming the risk, showing complete disrespect to and neglect for the families. Following complaints from residents, the SMH presented an old technical report prepared by GEO-Rio—Rio’s municipal entity for conducting geological assessments—which was challenged by residents because it was generic and did not correspond to the reality of the area.

It is important to note that the City did not involve the local community in the decision-making process in terms of considering alternatives to removal. In fact, the City failed to disclose information, acted in an authoritarian and aggressive manner, and abused its power, even applying psychological pressure to force residents to sign removal orders, all of which constitute serious violations of human rights. As a result, residents became apprehensive, not knowing where they would go and how they would re-establish their lives in places far away from their work and leisure. Some of them even became ill as a consequence. Two elderly residents had heart attacks a few days after the violent actions of City representatives.

In order to face these threats, residents created a committee and sought support from the Catholic Church’s favela outreach group Pastoral de Favelas, the Popular Council (Conselho Popular), and the Land and Housing Nucleus (NUTH) of the Public Defenders’ Office. Among the actions of resistance against removals were the families’ occupation of the Abelardo Chacrinha Barbosa Municipal School, the action of women and mothers to prevent a demolition by stopping a tractor driven by a City agent, and the elaboration of a technical counter-report. The counter-report was developed with input from residents by Maurício Campos, a civil engineer who, at the time, was a member of the support base of NUTH’s technical group. This counter-report identified a smaller number of houses that needed to be removed to allow urban interventions such as the stabilization of slopes and the structural reform of some houses, which would guarantee the safety of residents staying in the area. Thus, residents were able to challenge the validity of the City’s report that was being used to justify the removals by using depoliticized and generic technical language.

According to José Ricardo, president of Laboriaux’s Neighborhood Association and an activist who has played a significant role in the resistance movement, the City removed about 130 families from the area under the generic discourse of environmental and landslide risks. Some families received social rent of just R$400 per month as compensation, while others were resettled in My House My Life (Minha Casa Minha Vida) public housing complexes in Triagem, Estácio, and Cosmos. This resettlement had a damaging social impact on people’s lives through increased expenses, jobs lost, changes in schools and daycare centers, challenges to mobility, and the breaking of social ties due to former Laboriaux residents’ distance from the area where they had built their lives, as well as depression from the anguish and suffering caused by forced removals. It is worth mentioning that the removals were made by decrees, without recognition of residents’ rights to the land based on the land’s social function, in an arbitrary and truculent way.

Laboriaux residents, along with residents of other favelas threatened with removals such as Prazeres and Pavão-Pavãozinho, have united and networked further, conducting various debates and attending grassroots demonstrations and public hearings. The residents of Laboriaux also participated in Movimento Preserva Laboriaux (the Movement to Preserve Laboriaux), which organized collective actions to clean up garbage in the green areas around Laboriaux.

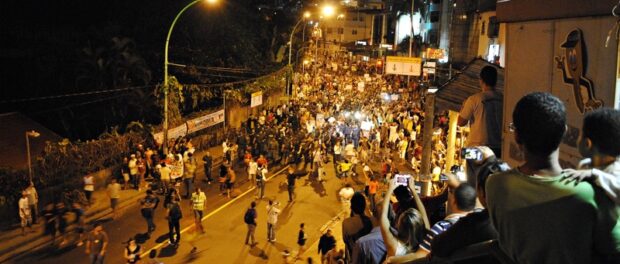

It is worth noting that four years ago, in the context of the protests in June 2013, about 4,000 residents of Rocinha protested to demand the implementation of public policies in the community. As a result of this historic moment, a committee of residents was able to present a list of demands to the state and municipal governments, leading then-Mayor Eduardo Paes to guarantee during a visit to Laboriaux that he would not remove anyone else from the community and that his administration would carry out urban renewal work in the area.

Through the collective actions of Laboriaux residents in their struggle to stay in the area, the community achieved some successes. The City re-opened the school, built a containment wall on one of its borders close to Gávea (a neighborhood with high-value real estate), and paved the main street, Maria do Carmo. However, the technical counter-report highlighted a small border area between Laboriaux and other areas of Rocinha as critical, but a containment wall has still not been built there. According to the City government, the bidding for this containment project was supposed to be open between 2012 and 2013, but five years have passed since then and residents have not yet received any news about it.

Although the direct Olympic legacy was forced evictions and the exacerbation of inequality and violence, the empowerment and networking of residents through resistance movements has unexpectedly also emerged. These residents have sought political training and information about their rights and what paths they must take to be able to influence the planning and execution of public policies in favelas. One example of this was the filing of an official letter to the Municipal Housing Secretariat to request an extrajudicial hearing to clarify the demands for the urban and land regularization process that was interrupted seven years ago. Another example is residents’ constant demands for improvements from the City, actions which have counted on the support of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and on legal assistance from NUTH.

The actions of residents demonstrate their commitment to remaining in the area and their demand for completion of urban projects such as containment walls, paved roads, and housing improvements, insisting on grassroots participation in all decision-making processes during the planning and execution of these interventions.

Simone Rodrigues is a lawyer. She was raised in Rocinha and has been a resident of Laboriaux since 2000.

To learn more:

COMITÊ POPULAR DA COPA E OLIMPÍADAS DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Mega-Events and Human Rights Violations in Rio de Janeiro Dossier: Rio 2016—The Exclusion Games. 2015.