On Sunday, October 8, 2017, the annual Rio de Janeiro International Film Festival hosted a screening of Canadian filmmaker Jason O’Hara‘s recently released documentary State of Exception at the Rio Museum of Modern Art’s Cinema. The film chronicles the concurrent struggles of the Aldeia Maracanã Indigenous movement and the favelas of Vila Autódromo, Vila Taboinha, Metrô-Mangueira (also known as Favela do Metrô), and Pavão-Pavãozinho against forced eviction during the lead-up to the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games. Present were several of the Indigenous leaders and favela residents featured in the film, who experienced firsthand this period of suspended civil liberties as Rio’s city government prepared to host visitors from around the world for the two mega-events. In a panel discussion after the film they elaborated on their communities’ ongoing struggles and expressed appreciation for the film’s coverage, joined on stage by additional community members who both praised and criticized the documentary’s portrayal of their movements.

As he addressed the audience before the screening, O’Hara described the documentary as a film belonging to all those present, referring to the seven-year process of working with the featured communities throughout the film’s production and editing phases. The movie is his third documentary focusing on civil rights, protest, and resistance. It opens with footage of Indigenous leader and linguistics professor José Urutau Guajajara riding the metro as audio of his voice describes the discrimination faced by indigenous peoples, who he says are imagined by the broader Brazilian population as primitive. A large portion of the film is spent following Guajajara and other Indigenous leaders originating from communities across Brazil in their occupation of the abandoned building formerly home to the Indigenous Museum, located in the shadow of the world-famous Maracanã soccer stadium. Since 2006, the movement, now called Aldeia Maracanã, has reclaimed this “micro-territory” from the city to create a space of Indigenous resistance in Rio.

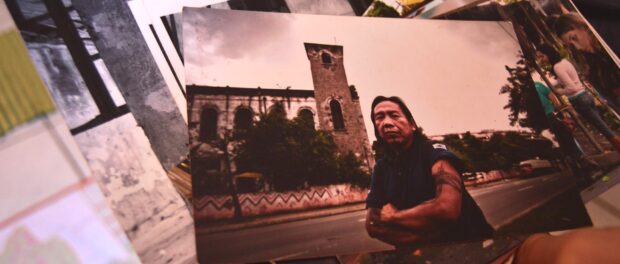

Carlos Doethyro Tukano, another prominent leader of the Aldeia, is also featured. In State of Exception, O’Hara has a keen eye for eviction events. The film shows the March 2013 removal of the Aldeia members by Shock Troops armed with riot shields, tear gas, and batons ahead of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, for which the neighboring Maracanã Stadium was undergoing significant renovation. During the assault on the building, Tukano is shown accepting the Rio city government’s offer for resettlement and leading part of the Aldeia group away from the violence. At that moment, Guajajara refused to leave and reoccupied the building with a smaller group of followers, but was ultimately evicted on the same day. After this point, the documentary follows each leader separately. Tukano and his group of 17 Indigenous families are shown relocated to stifling shipping containers in the former Curupaiti leper colony in Jacarepaguá in the West Zone, where they lived in cramped conditions for about a year. Then, the film includes footage of him accepting keys from President Dilma Rousseff at a public event to inaugurate apartments built through the Minha Casa Minha Vida public housing program in the Zé Keti complex of the North Zone‘s Estácio neighborhood. O’Hara’s lens zeroes in on Tukano’s life in these new apartments. He comments to the camera on the stark differences between the life he knew before, surrounded by plants and animals, and his existence in the spartan concrete apartments.

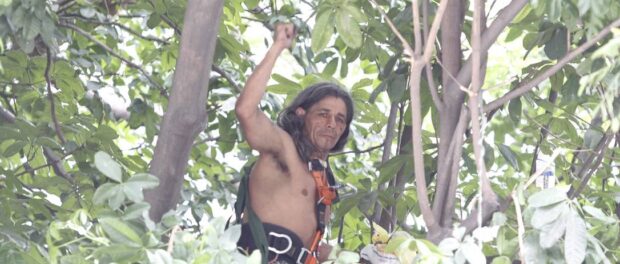

The film shows how in late 2013 Guajajara and a number of families reoccupied the Aldeia Maracanã site, rebuilding structures destroyed by the police and resettling in the building. While speaking at the discussion after the screening, Guajajara explained, “It’s one thing to think of land, another to think of territory. Land can be sold, exchanged. Not territory. Because the [Aldeia Maracanã] space is historic.” In a testament to his beliefs, Guajajara climbed a tree during a December 2013 eviction before the World Cup, staying there in protest for over 24 hours while police tried to remove him. The documentary shows this act of resistance and his following arrest.

After the screening, a founding member of the Aldeia who does not appear in the film, Araçari Pataxó, asked why the film did not include the history of the earlier years of the Aldeia and defended his and Tukano’s decision to accept the government’s housing offer. “If I hadn’t accepted the Zé Keti [housing complex], I would be on the street… It wasn’t selling out or about quality of life, it was about not being on the street. The film doesn’t show this. The film shows Tukano as selling out… I hope that it is revised,” he said.

In response, O’Hara expressed his belief that every social movement needs different strategies to succeed, emphasizing his support for Tukano’s decision and the steps he took to convey the complexity of the situation in the film, including engaging the Aldeia leader in the film’s editorial process. Tukano himself, who spoke next, focused on the story of his arrival in Rio and the process of meeting and uniting many disparate Indigenous groups. “Building is hard,” he said. “Destroying is easy.” Tukano stood firm on his decision to leave the Aldeia, saying “I was accused of various things, but these didn’t shake me. I’m prepared… I am here to dialogue now… The Indian now is unable to fight only with bow and arrow, they need to learn to use the pen.”

State of Exception has a broad scope, also addressing the stories of other communities that faced eviction. In a particularly striking sequence, O’Hara intersperses game footage from Brazil’s 2013 Confederations Cup victory over Spain with shots of police repressing the popular “Brazilian Spring” protests against increases in bus fares, police brutality, and World Cup spending in the context of severe national inequality. The film has a particular eye for the violent practices of Shock Troops and police on unarmed residents. They are shown using stun grenades and tear gas on a large group children during a Metrô-Mangueira eviction, a sound canon on Aldeia Maracanã members, and clubs on Vila Autódromo residents, including activist Maria da Penha.

O’Hara also manages to mount a criticism of the politics behind evictions in the name of mega-events. He captures the false promises of Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes about the supposedly positive impact and legacy of the World Cup and Olympic Games. Promotional videos for construction of the Olympic Park and shots of Rio’s affluent South Zone are placed alongside those of Vila Taboinha organizer Célio Gari’s visit to Pavão-Pavãozinho, a favela located high above the touristic Copacabana beach. There, he visits a resident who explains that his home was marked for eviction with the Municipal Housing Secretariat’s “death notice, “an ominous number spray-painted on the door alongside “SMH,” the Secretariat’s initials. Gari fought eviction in his own community and others. After the film, he spoke of “all the neglect, the dismissal that the professional politicians have for the people,” adding that “they love money, but they don’t love those who produce, those who really drive the Brazilian economy.”

Also featured in the film were Altair Guimarães and Jane Nascimento, leaders of Vila Autódromo’s powerful resistance to Mayor Paes’ plans to bulldoze the community located on the border of the Olympic Park in Rio’s West Zone. Guimarães, who suffered two previous evictions before moving to Vila Autódromo, is shown mobilizing residents and pressuring politicians before finally watching his home be destroyed. Gari, Guimarães, and Nascimento continue to be active in assisting other communities’ ongoing struggles to remain in their homes. Nascimento concluded the event’s panel discussion saying, “I continue my struggle today with the incentive that people, not just favela residents but middle class people and all the resisting communities that aren’t low-income, can unite… We can’t wait for the government to create anything for us. We are the ones who have to unite, and create, and go door to door.”

State of Exception will be screened two more times as part of the Rio Film Festival:

Friday, October 13, 8pm at the Instituto Moreira Salles

Saturday, October 14, 3:30pm at Estação NET Rio 3

Article updated for accuracy on April 17, 2018.