For the original in Portuguese by Marco Aurélio Barreto Lima published on Justificando click here.

Celebrating a birthday, especially when you’re young, is usually a joyous moment. It’s a time for reflecting on the achievements of the last year and forming hopes for the next period, the dreams to be achieved and the future that awaits us. Make no mistake, when I say generally joyous, it’s because hopes, dreams, and the future are only vague terms for many of our young people, who are denied the right to know the concepts behind these words.

In Brazil, from 2005 to 2015, 318,000 young people were murdered. 2,650 per month. 88 per day. 3 per hour. On average, 1 every 16 minutes. According to this statistic, as we read this text and have a coffee, another teenager will be the victim of homicide in our country. This is the reality shown to us by the Atlas of Violence, a June 2017 publication by the Institute of Applied Economic Research (Ipea) and the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety which analyzed Brazilian homicide data through 2015, cross-referencing information from the Ministry of Health and the Brazilian Annual Report on Public Safety.

According to official data, 47.8% of 15-29 year olds who died in 2015 were victims of homicide. If we focus on the age group with the highest risk, which according to the research is boys aged 15 to 19, this rate rises to 53.8% of recorded deaths, a true war scenario. And it is at this point that we must ask ourselves: what war are we fighting? Or what war are we sending our children into?

The answer to these questions is not singular—it is more accurate to understand the death of those who have barely reached adulthood as a combination of factors, among which the war on drugs, police violence, and the criminalization of poverty deserve highlighting. All these factors are directly related and share a common denominator: racism. It is impossible not to associate these three phenomena with a stark racial divide, given that the incidence of the three has a proven and particular impact on black people.

The war on drugs has been selectively incarcerating, giving the police carte blanche to violate communities, homes, and bodies. The State and public opinion increasingly condemn poverty and hunger, decreeing the death penalty in the streets: with the bullet of the police officer, by throwing water over the homeless, or by the hands of the middle class tying us to posts. Being black in Brazil was always considered a crime and “captains of the bush” [the term initially used to described slaves that supervised and punished other slaves, in this context being used to describe the police] were given a hunting license. We were always reserved for favelas, the gutter, and misery; this is the background of the homicides described above.

Furthermore, according to the same experts, “out of every 100 homicide victims in Brazil, 71 are black.” These data mean that “the black citizen has a 23.5% greater chance of being murdered than citizens of other races or colors, regardless of their age, gender, schooling, marital status, and residential neighborhood.”

In conclusion: regardless of the scenario or the perpetrator, those who die are of a certain race.

What, then, is the solution to this absurd extermination of our black and peripheral youth? For some, the way out of all the violence that makes blood gush through the channels of our cities is to arm the population even more. This is what is called for, for example, in the 7282/2014 bill currently underway in the House of Representatives, which facilitates the purchase and possession of arms and ammunition, and whose authorship can be attributed to populist right-wing Rio congressman Jair Bolsonaro.

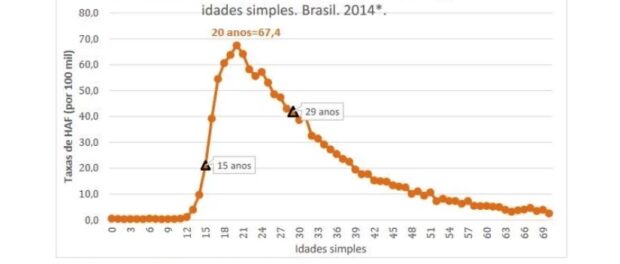

However, if we look again at the statistics, we will find that Brazil holds a prominent position in its rate of firearm deaths, a record number when compared to countries with armed conflicts throughout history. Again, the outlook is even worse for our youth, as “one can see the huge concentration of fatalities among young age groups, peaking at the age of 20, when firearm-related homicides hit a staggering 67.4 deaths per 100,000 young people.”

Thus, it remains obvious that those who advocate this type of measure ignore reality or even attempt to cover it up for illegitimate reasons, other than the public interest, given that a brief consultation of the 2016 Map of Violence would be enough to conclude that the bullets are being discharged disproportionately on our backs, the backs of the poor black youth. After all, if “proportionally 71.7% more black than white people die” as a result of firearms in Brazil, it does not seem reasonable to think that more weapons could have any impact on that statistic other than the increase in racial violence.

What interests us is nothing more than the chance to dream, to smile, to go home and come back safe without being approached by a [police] car or having fingers pointing at us. For centuries we have struggled for the basic right to live, and it has yet to be conquered!

“At age 20, some celebrate another year of life, but we are only able to commemorate one more year in which we did not die.”

Marco Aurélio Barreto Lima is a black law student receiving a scholarship to attend the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP), a Research Assistant for the State and Civil Society Project, and a student leader of the August 22 Academic Center of the Faculty of Law of PUC-SP.