For the original article in Portuguese by Gabriele Roza published by investigative news agency Agência Pública click here.

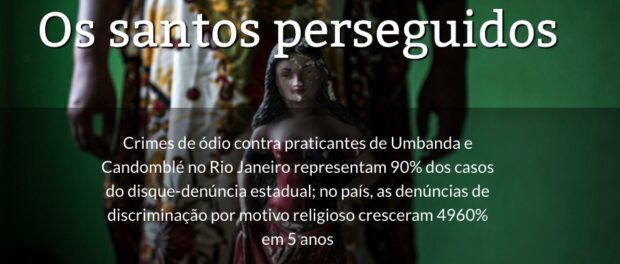

Hate crimes against practitioners of Umbanda and Candomblé in Rio de Janeiro represent 90% of the cases called into the state of Rio’s public complaints hotline; nationwide, reported cases of religious discrimination increased 4960% in 5 years.

[For historical context on the current discrimination facing Afro-Brazilian religions, don’t miss the section entitled “A past that returns” at the end of this story.*]

Mother Merinha was very fast, she tied a white cloth to her clothes, and slipped some necklaces made of colored beads around her neck. “The saddest part of all this is knowing they do not stop,” she said, as she tied another white cloth around her head. She was ready, in her mãe-de-santo priestess dress. She signaled that we could begin the interview and introduced herself: ”I am Mother Merinha de Oxum, I was initiated in Candomblé 36 years ago, I am the daughter of Mima de Oxossi, of Ilê Axé Obá Ketu.” One year and a half ago, Rosimere Lucia dos Santos opened a Candomblé terreiro, or sacred site, in Belford Roxo, a municipality in Rio’s metropolitan area, in the Baixada Fluminense, where she also started a social project with children in the region. On Wednesday, September 27 she turned 51, and on that same day her terreiro was invaded and burned.

The neighbors, when they noticed the flames, called Mother Merinha’s brother, who lives nearby, to help put out the fire. The fire was controlled before it affected the main building, but the next day, Mother Merinha noticed that they had set fire in the middle house, where the donations, the religious dress, and the orixás were. The criminals also stole a TV, cell phone and radio. The police report was completed a week later, on the second attempt: “The police station was very crowded, I stayed there for about three hours, I was very weak, I was shocked by everything that had happened, I was gathering strength, and then returned on Thursday.”

They also burned books about Afro-Brazilian religions and photos of the family’s history with Candomblé. ”What saddens me most are the work materials and the photographs. I have a whole history with Candomblé, shaped by my mother.” Mother Merinha is a descendant of black and indigenous ancestors, and she inherited the religion from her maternal grandmother who went to Rio de Janeiro to flee from her violent husband in Espírito Santo, a bordering state. A washerwoman, her grandmother was able to buy a plot of land in Belford Roxo and dedicated part of it to her daughter’s orixá. “I even had some photos of my mother carrying a bundle on her head when they arrived in Belford Roxo,” she recalls. “Over the years I brought everything I had to this place. It’s a whole life story of the sacred.”

Mother Merinha is one of the most recent victims of violence against followers of Afro-Brazilian religions in the State of Rio de Janeiro. According to data from the Center for the Promotion of Religious Freedom and Human Rights (Ceplir), of the 52 reports of religious intolerance to the Ceplir—from December 2016 to August 2017—34 were from followers of Candomblé, Umbanda and other denominations of African religions in the State of Rio.

In five years, reports denouncing religious discrimination in Brazil grew 4960%. The number went from 15 in 2011 to 759 in 2016, according to data from Disque 100, a hotline for the Secretary of Human Rights to the President of the Republic (SDH). In 2016, 69 were from Candomblé practitioners (9.09%), 74 from Umbanda practitioners (9.75%) and 33 from followers of what were broadly described as “religions with African roots” (4.35%), totaling 23.19%.

According to a Pew Foundation report, of the world’s most populous countries, Brazil went from being one of the countries with the lowest rates of Social Hostility with religious motivations, in 2007, to having one of the highest rates in 2014, going from second to ninth place in this period.

In August and September of this year, a new wave of attacks on Candomblé and Umbanda terreiros in the Baixada Fluminense showed that religion-based hate crimes are growing in the state that has, for the first time, an evangelical bishop governing its capital—in January, Marcelo Crivella (PRB Party), bishop of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, became the mayor of Rio de Janeiro.

In response to the violence, the State Human Rights Secretariat (SEDHMI) launched the Fight Against Prejudice Hotline to facilitate complaints.

In August and October, 43 complaints were filed: one from a Kardecist spiritist, one from an evangelical Christian, two from Muslims, and 39 from Umbanda and Candomblé practitioners, representing 90% of the total. There were six types of violations identified, including invasion/attack on religious institutions (11), discrimination/defamation (10), physical aggression (6), incitement to hatred (6), verbal aggression (6), and threats (4).

Inquisition by Traffickers in the Baixada

Among the complaints against practitioners of Afro-Brazilian religions, 12 occurred in the Baixada Fluminense. The region gathers 13 of Greater Rio’s municipalities and houses at least 274 terreiros, out of a total of 847 in the state, according to the Mapping of Houses of Afro-Brazilian Religions, developed by the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) with support from the National Secretariat for the Promotion of Racial Equality Policies (SEPPIR / PR), between 2008 and 2011.

SEDHMI received four reports of attacks on terreiros carried out by drug traffickers from August to October, three of them occurring in the Baixada Fluminense, two in Nova Iguaçu and one in Itaguaí. According to the secretariat, the four victims reported that the local criminal faction had ordered the prohibition of the practice of religions with African roots in the area dominated by the faction. All those who report cases of religious intolerance are told to report to the local police station, but some victims do not do so out of fear.

In September, the terreiro of the priestess Carmen de Oxum was attacked in Nova Iguaçu. The trafficker, who even recorded the crime with a cell phone camera, gives orders to destroy the sacred objects: “Break everything, put out the candles, for the blood of Jesus has power… All evil must be undone in the name of Jesus.” According to the General Director of the Baixada Fluminense Police, Sérgio Caldas, the case is being investigated by the 58th Police Precinct (DP) and two traffickers of the Third Pure Command (Terceiro Comando Puro), a criminal faction known to threaten observers of Candomblé and Umbanda, have already been identified as perpetrators. “This person came from another community to put pressure on the Candomblé terreiros,” Caldas said to Pública, adding that conditions “are not favorable” to the investigation. “When it occurs in a community controlled by drug traffickers, the victims are afraid to expose themselves.”

Those indicted in this case will be penalized by Law 7.716 of 1989, known as the “Caó Law,” which determines the punishment for crimes resulting from discrimination or prejudice based on race, color, ethnicity, religion or national origin, as a non-bailable and imprescriptible crime. The penalty is two to five years imprisonment.

The babalaô priest Ivanir dos Santos, founder of the March in Defense of Religious Freedom and spokesman for the Commission to Combat Religious Intolerance, says that the first incidences of traffickers destroying terreiros happened in the 1990s, in Morro do Urubu, Pilares, in Rio’s North Zone. Later, other cases occurred in Morro do Dendê (located on Ilha do Governador), in Lins de Vasconcelos and Cidade Alta. “It’s an understandable phenomenon. Any religion that grows will influence some social spheres,” he says. Ivanir believes that the presence of evangelical churches in the prisons of Rio is an influencing factor in the emergence of what he calls “evangelized trafficking.” “The guy is imprisoned there, he becomes an evangelist and he’s going to get out for good behavior, which reduces his sentence… After leaving prison, not everyone changes their lives,” he says.

The evangelical churches will likely become even more present in the prisons of Rio de Janeiro. In February, the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God signed an agreement with the state government for the construction of temples in penitentiary units, funded by the religious institution. The agreement allows the Universal Church to build or rebuild ecumenical temples in the state’s 51 prisons, dependent on the authorization of the unit’s director. So far, thanks to the agreement, 15 temples have been inaugurated or renovated, in the prison complexes of Gericinó, Campos, Resende and Água Santa.

The Public Prosecutor for the Prison System and Human Rights of Rio de Janeiro visited the prison units where the religious temples were built to determine the validity of the agreement. According to prosecutor Murilo Nunes de Bustamante, the spaces are not supposed to be linked to a specific religion, but their architectural pattern resembles that used by the Universal Church. “Despite the plan that they would be ecumenical and freely used by anyone, the inmates themselves would only allow some religions to perform their worship there.” The prosecutor’s investigation has not yet been completed. “The indications follow the sense of the architectural identity of the spaces, which will be discussed with the churches operating in the prison system,” he said.

In response to Pública, the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God reported that its ‘Universal in Prisons’ (their social program serves 80% of Brazil’s prison population, approximately 500,000 people out of a total of 622,000 inmates according to Infopen in 2014), “offers courses and support to detainees and their families, carrying out a resocialization project that is recognized by the authorities of all the nation’s states, including in the state of Rio de Janeiro.”

Eight homicides for religious intolerance

The data available in the Report on Intolerance and Religious Violence by the Special Secretariat for Human Rights detail what religious freedom activists call a “Holy War.” The report shows that, between 2011 and 2015, 27% of the complaints made to the country’s ombudsmen were by followers of Afro-Brazilian religions, 16% by evangelicals, 8% by Catholics and 7% by spiritists. Regarding the religion of the aggressors, as reported by the victims, the data indicate that 17% were evangelicals. Catholics appear in second position, but very far away, with 3%, followed by Jehovah’s Witnesses (1%), spiritists (1%), and followers of Afro-Brazilian religions (1%). In 73% of the cases, no information on the religion of the aggressor was recorded.

Eight homicides for religious reasons were also identified in the report, according to investigations by the Civil Police or the Public Ministry. Four deaths involved Candomblé leaders in Londrina (PR) and Manaus (AM), and four were deaths within the same evangelical family in Itapecerica da Serra (SP). All the murders were carried out with knives, and the aggressors and victims knew each other.

Professor Jayro de Jesus, coordinator of the Ubuntu Free School of Afrocentric Philosophy and Theology, explains that Neo-Pentecostals understand their faith to bring health, well-being, and material prosperity. Illness, unemployment, and poverty result from “evil” and from a life of sin. “It is the evil that harms others’ lives. And [for them] evil is typified in Afro-Brazilian religions,” he explains. “Neo-Pentecostals now count on the help of the people themselves who find justification for ending the evil that is their neighbor.”

In the 1980s Jayro de Jesus, a historic figure in the struggle against violence against Afro-Brazilian religions, coordinated the Orixás Tradition Project, which visited terreiros in the Baixada to hear reports of intolerance, and referred them to police stations. “There were 20 young people who went out all over the Baixada. We identified 3,000 terreiros with complaints of invasions, name-calling, stoning, bible beatings,” he recalls. “Essentially the persecution came from the Universal Church,” he says.

The reports to the group were consolidated in the “The Fabricated Holy War” dossier and submitted to the federal government in 1989; it was then filed with the Public Prosecutor’s Office. But nothing was done, affirms Uilian Portella, the group’s lawyer. “The dossier denounced repeated aggressive attitudes of the Neo-Pentecostal evangelical churches, notably the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God… The followers of Afro-Brazilian traditions were being stoned, and beaten with bibles to ‘expel the devil.'”

In 2015, the television networks Rede Record and Rede Mulher (purchased by Record)—owned by Edir Macedo, founder and leader of the Universal Church—were sentenced by the federal judiciary to air four television programs to fulfill followers of Afro-Brazilian religions’ right to respond to offensive material against them displayed in the network’s “Mysteries” (Mistérios) and the “Exorcism Session” (Sessão de Descarrego) programs.

When contacted by this reporter, the Universal Church claimed that the accusation that its members were persecuting other religious groups in the 1980s is “untruthful.” “The Universal Church of the Kingdom of God defends, without compromise, the freedom of thought, belief and worship, as guaranteed by our federal Constitution.” The Church says that it preaches the contrary. “We encourage our adherents to respect the convictions of other people, because it is precisely the bishops, pastors and millions of supporters of the Universal Church who are the main victims of religious prejudice in Brazil,” it said in a written statement.

”It’s as if they had taken a child”

At 10pm on October 4 of this year, Candomblé priestess Mother Vivian de Souza was at home in Nova Sepetiba, in Rio’s West Zone, when she received a call from a neighbor of her terreiro in Seropédica, in the Baixada Fluminense. On the phone, he said that the house of worship had been broken into, and by that time, many images and objects had already been broken. The neighbor passed on the threat that if she did not remove the belongings as quickly as possible, they would destroy everything. Mother Vivian fell into despair. Her terreiro is an hour away by car.

Almost two years ago, Mother Vivian moved with her family to Nova Sepetiba and transformed her former home in Seropédica into a Candomblé house. She did not visit the terreiro on a regular basis, but could stay there for a whole week or just a weekend, “for as long as religious obligations demanded.” When she reached the house, around midnight, she saw the broken-in gate, the Orixá Bará on the floor, the broken Exus. She got a truck to remove what was left. The next day, she rented a house in Sepetiba to begin construction of a new space dedicated to the orixás. She does not want to go back to her previous home: ”It’s as if they’d taken my child.” Besides the orixás, they destroyed the very structure of the house and other objects, “things that are very valuable to us. A cowrie-shell, a coin is valuable to us. To other people maybe not, but this is very bad,” she said.

The new house is smaller; symbolic objects were stored in one room, and other objects in a living area, with the atabaque drums and mattresses she was able to take with her. “I can’t understand all this hate. It feels as if I am in the time of my ancestors, when we had to hide in the woods, as my grandparents did to continue to practice our religion. I’m trapped, they’re cornering us more and more.”

Mother Vivian went to the police station in Sepetiba to file a report, but was advised to fill out the police record online or go to the Seropédica police station. “The way they act is like you’re responsible for what’s going on. ‘Why were you not there at the time?’ I’m not the one who has to know who it was.” For her, the police show no interest in conducting an actual investigation.

With the crisis, the end of the Center for the Promotion of Religious Freedom

Mother Vivian sought help from the Center for the Promotion of Religious Freedom and Human Rights (Ceplir) which, from 2012 until this year, assisted the victims of intolerance in the State of Rio with psychological, legal and social assistance.

However, Flávia Pinto, who was director of the institution until this week, explained to Pública that the Center stopped receiving resources from the state government in 2016. “With the state’s crisis, Ceplir was scrapped. We were able to get some support from the Palmares Cultural Foundation [of the federal government] and we put Ceplir to work for another year at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), but these resources have run out,” she said. “We are making people aware that religious intolerance is a crime. Policies related to religious freedom are still in a very early phase in this country. People still do not have the understanding that being discriminated against due to their religion is a crime.”

The State Secretary for Human Rights, Átila Alexandre Nunes, rebuts the criticism. According to him, the State Secretariat for Protection and Support for Women and the Elderly became the State Secretariat for Human Rights and Policies for Women and Seniors (SEDHMI) and, with the change, the secretariat will incorporate the Ceplir staff as early as November “so that it is a permanent, consolidated structure that does not rely on third-party resources.” Even so, Ceplir will not run its services in November, Black Awareness Month, according to Flávia Pinto. She is now going to work at Rio’s Municipal Human Rights Office.

In August, the Secretary announced that the state will create a police station specialized in the fight against racial crimes and crimes of intolerance, DECRADI, with a group capable of carrying out investigations and assisting victims of hate crimes.

These services still have a lot to improve, says Flávia Pinto: “The cases of intolerance are still interpreted by the police as disputes among neighbors, and then the person does not receive the correct care and the data are not generated.”

Regarding the budget problem, the Secretary believes that the action may unburden the regional police stations that will be able to refer investigations to the specialized police station. “We are talking about a leaner structure, the Secretariat of Human Rights would make psychosocial counselors available to support and help victims.”

“Unfortunately, we are experiencing a new moment in which traffickers are persecuting the terreiros. The logic now is a territorial logic due to these traffickers,” says the Secretary. Violence by traffickers stimulates an increase in the number of unreported cases and makes the work of the police more difficult. “In the case of Mother Carmen, there were almost 10 traffickers, according to her report. We even accompanied her to the police station, but she did not want to sign the testimony out of fear,” he says. He adds that there is a sense of impunity due to these cases not being treated seriously and reported as religious intolerance.

Police commissioner Henrique Pessoa, of the 151st Police Precinct in Nova Friburgo, coordinated the Anti-Intolerance Nucleus of the Civil Police, which consolidated the information from reports received by the Commission to Combat Religious Intolerance. “This advisory in the police stations—our job was to raise awareness among police of the relevance of the investigation. The problem cannot be tackled in a trivial way. But unfortunately, the police work in precarious and inadequate conditions.” The nucleus was closed in 2012 during the restructuring of the Civil Police under the administration of former governor Sérgio Cabral (PMDB).

Mother Elaine and Father Márcio

Elaine Dias Pereira, whose religious name is Mother Elaine de Oxalá, has lived in Nova Iguaçu for 30 years—and for 30 years she has been persecuted for her religion. She says that as soon as she started the Candomblé house in Santa Rita, a neighborhood in Nova Iguaçu, they set fire to the columns of the house. Even today, they constantly throw stones at the tiles. As of last December, she has not filed a complaint or report at the police station. But at that time, a bomb exploded on the terreiro‘s electric meter while a religious ceremony was taking place. “There were a lot of people, lots of followers of the faith here in the house. There were children, pregnant women, and the explosion was scary. When the bomb went off we had no idea what was happening.”

She went to the police precinct (58th) to report the case. “To my surprise, I was very well assisted and the case was registered as religious intolerance. It was a victory. I came back here happy because I had managed to do that.” A police inspector visited the house the next day. “The case did not go ahead, an investigation was never followed through until the end,” she says. After the episode, she decided to put two cameras in front of the terreiro, which prevented further aggressions.

Father Márcio Virginio also had to put a camera in the yard of his terreiro in Penha, in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, to identify the individuals throwing stones and trash in the Candomblé house. The house has been open for three years and, from the second year onward, the attacks began to occur on the same days, Monday and Saturday, always at the time of a ceremony. “The stones come from the building next to us, and the camera is not so good, so I’ll spend more money to buy a better camera.” In addition to breaking parts of the roof, the attackers have also broken an image of Caboclo, an orixá worshipped in the house. “When we find a broken image of a spirit it makes me sad, because it is the home of our sacred entity.”

He had to put tarpaulin in the open part of the courtyard so that people would not be hit by the stones being thrown at them during religious ceremonies. “My house has a lot of old people, people who come in wheelchairs. People already arrive in fear.”

Father Márcio went to the police station when the assaults started to become more frequent. “The first time they [the police] did not file an incident report. Only the second time.” He says he went to the station at least 20 times to make more complaints. “They did nothing,” he says.

Advocates of religious freedom see a link between police inaction and prejudice. Ivanir dos Santos argues that a key step, which is pending, would be the implementation of teaching of African and Afro-Brazilian history and culture in schools, in accordance with Law 10639. The fault lies with the lack of knowledge. “It’s no use putting the blame only on Neo-Pentecostals because it’s not just them. To the whole Brazilian of society we are sorcerers, witch doctors, and evil,” he explains.

On September 27, the federal Supreme Court authorized religious teaching in public schools—that is, classes can follow the teachings of specific religions. For Ivanir dos Santos, the effect of the ruling will be to increase discrimination and persecution of Afro-Brazilian religions. “This recognizes the role of the church as an element of the State, this is just like in the colonial period and the empire,” he says. Jayro de Jesus agrees that religious education reinforces the duality between good and evil. “The churches feel that they hold what is good, not only for the soul, but for social life. So religious education in schools incentivizes this duality,” he says.

Without knowing the religion, it is difficult for society to understand the seriousness of these attacks. In the African worldview, the arrangement of the orixás is a kind of “extension of the self,” of existence itself, explains Professor Jayro de Jesus. “This violence is much more aggressive than you think.” Disrespecting religious leaders and Afro-Brazilian symbols of representation, he says, is understood as a form of expulsion. For many people, after such destruction, it is necessary to rebuild oneself in another physical space.

In order to rebuild herself, Mother Merinha counted on a mutirão of volunteers who helped physically clean her house swept by the flames. Now, she prepares the ritual of religious cleansing, with prayers for the Pretos Velhos spirits. “We are going through a time of great religious intolerance in our country, which is getting worse every day. I do not know if everyone knows this, but our space unfortunately also has become part of this statistic of hatred,” she wrote to her followers.