Initiative: Pro-Sanitation and Environment Movement of the Parque Araruama Region (Movimento Pró-Saneamento e Meio Ambiente da Região do Parque Araruama)

Contact: Facebook | Email

Year Founded: 2011

Community: Parque Araruama Region – São João de Meriti, Greater Rio

Mission: “We are a non-partisan and secular movement of residents of the region of Parque Araruama who have met since the beginning of 2011 to reflect and propose alternatives that guarantee social, environmental, cultural, and economic rights. We fight for the social control of public policy, programs, and governmental programs. We are open to dialogue with all forces of society that engage in the construction of a socially and environmentally just city.”

Public Events: The MPS hosts discussions, lectures, and workshops on topics related to sanitation and the environmnet in the Baixada Fluminense.

In many of Rio’s informally established communities, nonexistent or poor-quality sanitation infrastructure is a constant reminder of a long history of neglect by municipal, state, and federal governments. In the Baixada Fluminense, the region in the northwest of the Rio Metropolitan Area home to approximately three million people, access to water and sewer systems is especially lacking. In the Baixada municipality of São João de Meriti—nicknamed the ‘anthill of the Americas’ for having one of the highest population densities on the continent—only 48.86% of the population has access to a formal sewage system, according to 2015 statistics from the Brazilian Ministry of Cities. The NGO Trata Brasil ranked São João among the ten worst Brazilian municipalities with populations over 300,000 for its sewage infrastructure, and residents are consistently frustrated by ineffectual public sanitation policy.

The Pro-Sanitation Movement (MPS), an intergenerational group of activists from the region of Parque Araruama in São João de Meriti, recognizes that sanitation is political. They engage in a variety of activities, from hosting public debates around the right to the city and sustainable development to lobbying the municipal government for more equitable policy around water, sewage, and waste in their communities. Their efforts fuel conversations around sanitation in São João de Meriti and demonstrate how effective public mobilization can hold governmental public works projects accountable to the needs of residents of Rio’s peripheral communities.

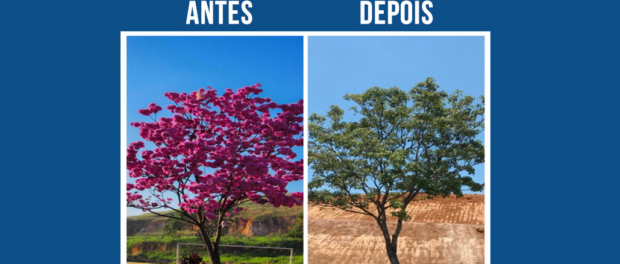

The MPS’s most recent campaign illustrates how the group operates. Several days of heavy rains in November of 2017 brought an unpleasant surprise to residents of the communities surrounding what is known as the Morro do Shopping—the large hill next to the Grande Rio Shopping Mall. Rivers of muddy brown water gushed down the slopes, flooding streets and homes in the community of Venda Velha and Parque Juriti. The mud clogged already deficient sewer systems and threatened the health and livelihood of the local population. The Morro do Shopping, once one of the last remaining green spaces in the municipality, had been stripped bare of its vegetation when bulldozers appeared without warning in January of 2017. They quickly leveled the hill and exposed the loose earth that turned to mud when the rains came—all to pave the way for the construction of massive warehouses.

Initially, residents of the communities around the hill did not know why it was being deforested. The MPS obtained an audience with both the Secretaries of Public Works and the Environment in São João de Meriti and found that an American company, Prologis, had partnered with Brazilian developer Cyrela Commercial Properties to advance the warehouse project. A municipal environmental impact assessment (0145/2016) green-lighted the project, but MPS members say neither the developers nor municipal officials consulted or informed the surrounding communities about the construction. One member of the MPS movement, Paulo Machado, described the area destroyed for the Morro do Shopping project as “the lungs of the region.” It was a green space home to animals like monkeys, birds, and snakes as well as recreation area for locals. A community soccer project for kids and youth had also previously used the fields destroyed by the bulldozers while clearing the hill.

Former MPS member José Lopes warned that the deforestation of the Morro do Shopping will have long-ranging consequences beyond increased flooding, in light of global climatic changes. “They cut the trees. Only when the heat reaches 80 degrees, when they start to die—when people here start to die—will they remember the Morro do Shopping. Which wasn’t a dry hill,” he told RioOnWatch. Trees can reduce runoff-induced erosion by 600 times and can absorb 30-60% of precipitation. The loss of tree coverage is a significant contributor to landslides, a growing risk as rains intensify across Rio state due to climate change.

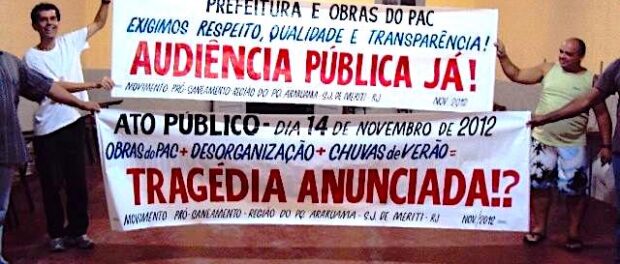

The MPS organized two protests at the construction site in partnership with the Venda Velha Residents Association and a local syndicate (SITICOMMM) of construction workers who had not benefited from the purported jobs the project promised to create. MPS members also contributed to a Meriti TV story on the flooding to raise awareness around the issue. In January 2018, the MPS learned in a meeting with the engineers contracted by Prologis that the company had committed to giving residents compensation for flood damages, as well as cleaning the sewage system affected by the mud. The MPS also presented their compensatory demands to the engineers. Along with the immediate preservation of a natural spring and vegetation that survived the initial construction, the list of reparations for the lost green recreation space included plazas with sporting equipment, a bike path around the hill, reforestation, and the construction of a federal technical school in the region.

The type of mobilization strategies employed by the MPS in the Morro do Shopping case arise from a history of residents’ movements in the Baixada, according to MPS activist and Parque Araruama local Tânia Cubiça. “Towards the end of the 1980s, beginning of the 1990s, the residents associations and NGOs started to appear with a lot of force here in the municipality of São João,” she said. These groups fought for the needs of local communities, drawing attention to inequalities in exposure to violence, access to education and health, and sanitation. These issues affected Baixada communities composed predominately of migrants, often from Brazil’s rural Northeast, who emigrated in mass numbers to settle in Rio between the 1950s and 70s as the city industrialized. Lopes explained that when he arrived in Parque Araruama in 1970, “it was all northeasterners, Portuguese immigrants, and people from Minas Gerais,” a Brazilian state bordering Rio.

The residents’ associations—and later the MPS—grew out of an activist tradition within the Catholic Church and other Christian denominations in Latin America. Also in the 1970s, the Basic ecclesial communities (EBCs), community-based Christian groups that worked for social justice, proliferated in Brazil. Their underlying ideology was liberation theology, an interpretation of scripture that emphasizes concern for poor and oppressed peoples. EBCs grew partly as resistance to human rights violations that took place under the Brazilian military dictatorship in the 1970s and 80s, including political repression and torture. They employed a “see-judge-act” methodology, which combines stages of critical reflection and conversation with the requirement of concrete actions to solve social issues.

The MPS arose from the “act” phase of this method during the 2011 Fraternity Campaign, an event organized yearly by the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops (CNBB) to incentivize social action on the community level. The theme of the 2011 campaign was “Fraternity and Life on the Planet,” meant to provoke conversation on issues of global climate change in Brazil. In Parque Araruama, this meant discussing public drainage projects happening in the region that year to combat flooding, an issue in many areas of the Baixada. The MPS emerged as the concrete result of the campaign and a desire to assure that these R$10 million projects actually solved the issues they were meant to address. A founding figure was Father Adelar, a fixture of the Catholic Church in Parque Araruama and an ex-city councillor in São João.

“Father Adelar mobilized more than just the Catholic Church,” explained Cubiça. “He called all of the people in the whole area to discuss the question of sanitation.” Adelar focused on uniting residents from different communities and political allegiances within the MPS, which has always operated as a non-denominational and non-partisan organization despite its origins in the methodology of the church.

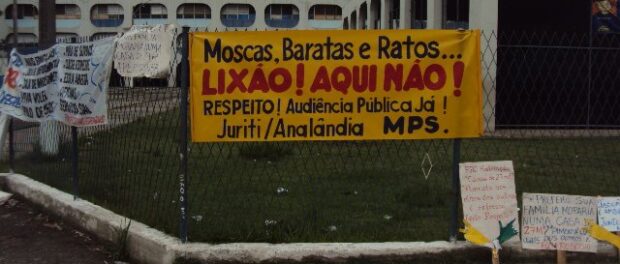

The MPS quickly began acting to address injustices in the Parque Araruama region. In 2012, the group prepared a report for the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF) in São João de Meriti detailing how public money was wasted in an urban upgrading project in nearby Parque Analandia. There, the community was slated to receive 180 homes, a health clinic, and new paved roads sponsored by federal money, but the company carrying out the public construction contract went bankrupt in 2012, halting the project. After several years of inaction, the municipality demolished what little construction had been started, an act the MPS viewed as an attempt to hide the failed project.

The core group of organizers in the MPS numbers less than twenty, but the group counts on a larger network of residents who show up when the organization’s actions require greater popular involvement. Much of their work focuses on civic education and public debate. They often host lectures and discussions on sanitation issues in São João de Meriti. Currently, the group is trying to build momentum behind recycling in the community. Silvana Vieira, an MPS member involved in this area, told RioOnWatch that in December 2016 the group held a collective workday, or mutirão, called “Recycle Araruama.” On that day, local residents and business owners brought recyclables to a public square, where the MPS collected them, promoting recycling practices and their movement’s ideals. This is now an annual event.

The MPS also responds to local policy developments around sanitation in São João de Meriti. In 2017, they focused on the move the São João municipality made toward privatizing water and sanitation services by awarding them to Águas de Meriti, a private company whose investors include an investment fund based in Singapore. The MPS published an informational pamphlet about Águas de Meriti and distributed it, so residents would know what the privatization meant in practical terms, ensuring informed democratic engagement in the debate around public services. As of April 2018, the privatization project was on hold, due to difficulties in negotiation between Águas de Meriti, the municipality, and CEDAE, Rio’s state water utility (which seems to be headed toward privatization itself).

The most active members of the MPS group shift with the passing of time, but its commitment to holding public power accountable around sanitation issues does not. Cubiça explained the MPS’s position with a particularly resonant metaphor for those who have experienced Rio’s muggy summer nights: “We are those annoying little mosquitos buzzing in your ear all the time. You want to sleep, you swat and swat, but we don’t leave. I think the MPS is that mosquito that disturbs sleep, that doesn’t allow complacency and doesn’t give up. We were created with the objective of fighting for the common good, to look after the betterment of the quality of life here. While this isn’t happening, we will not stop.”

*Movimento Pro-Saneamento is one of over 100 community projects mapped by Catalytic Communities (CatComm), the organization that publishes RioOnWatch, as part of our parallel ‘Sustainable Favela Network‘ program launched in 2017 to recognize, support, strengthen, and expand on the sustainable qualities and community movements inherent to Rio de Janeiro’s favela communities.