This is the third article in an ongoing series on the Brazilian electoral political scene in 2018.

On February 16, President Michel Temer authorized a federal military intervention in Rio de Janeiro that will last until December 31 of this year. Military involvement in Rio’s public security is nothing new. Armed forces played a role in Complexo do Alemão in 2010 as part of a strategy which culminated in the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) in the community. They also were active in the city during the sports mega-events and occupied Complexo da Maré between 2014 and 2015 at a cost of R$600 million (around US$185 million).

In addition to these cases, a contingent of 9,000 soldiers was in the streets of Rio in the days before carnival in 2017 at the request of Governor Pezão, who claimed it was “necessary due to the increase in the number of people in the city.” Back in July 2017, then Minister of Defence Raul Jungmann announced that armed forces would “assist with public security” in Rio until the end of 2018. In September and October, residents of Rocinha had to live with repeated army occupations, which extended as far as four favelas in the Baixada Fluminense. In November, a joint operation by the army and Civil Police culminated in the slaughter of eight people in Complexo do Salgueiro, in São Gonçalo. In January of this year, approximately 3,000 soldiers joined the police in a concerted action in Jacarezinho which lasted more than a week.

As opposed to previous decisions, however, the decree authorizing this intervention poses the risk of permanent military action without an end date. Individual campaigns under the current intervention do not require the customary presidential order to trigger the Guarantee of Law and Order (GLO) article, a constitutional mechanism that allows the use of military force to help maintain public security when police forces are not enough. With this new decree, not only the execution but also the planning of public security in the state of Rio de Janeiro fall into the hands of General Walter Souza Braga Netto, the federal appointee who answers directly to the president and who is now in charge of the State Security Secretariat, the Military and Civil Police, the Firefighters Corps, the Criminal Justice Administration, and even gubernatorial duties which relate directly or indirectly to public safety. The implementation of military force is therefore no longer in the hands of the state governor. State policies which interfere with measures taken by the federal appointee are rendered irrelevant, such that soldiers will be at complete liberty to carry out campaigns.

Despite the intervention already having congressional approval and despite there already being troops on the ground (with action taking place in Favela Kelson’s in the North Zone and Vila Kennedy in the West Zone, in addition to in the Milton Dias Moreira Prison in Japeri), in his first press conference Braga Netto himself said that it was still necessary to conduct studies and lay down a plan for intervention. Lack of planning aside, there are no data that support the need for intervention. The intervention was justified based on a supposed spike in violence during carnival, even though the director of the Institute for Public Security (ISP) has denied any such spike, attributing feelings of insecurity to a narrative bolstered by mainstream media which is not reflected in any index. The decision to intervene in this form has not been seen since the country redemocratized in the 1980s, and there are fears that this might set precedents for military action in areas beyond security in the long term, and for deeper militarization and intensification of violence in the short term.

Impact on residents in favelas and the periphery

The immediate sense of security—besides being selective and inadequate to deal with deeper issues surrounding public safety, such as the flow of arms and the war on drugs—comes at the expense of the insecurity of a significant part of the population: black people and favela residents. Since houses were already invaded without warrant and people were subjected to random arrest and even disappeared as a result of police activity, it is scary to imagine what could happen under the armed forces, trained in military combat rather than policing. Even before the intervention has begun in earnest, favela residents have already had civil liberties, such as the right to come and go, violated. In Vila Kennedy, soldiers have been stopping and registering residents, taking pictures of their faces and identification on their personal devices, and delaying residents’ commutes to work. Additionally, then Minister of Defense Raul Jungmann declared that collective search and arrest warrants would be granted, treating residents as suspects and providing carte blanche for soldiers to enter not only particular houses under suspicion, but any house in a street, region, or neighborhood, increasing the likelihood of arbitrary action and rights violations.

Beyond that, there is a dangerous potential that violations against the lives of residents will be treated with impunity. That’s because, unlike with the police, homicides committed by members of the armed forces are judged in military courts. This includes homicides that occur during GLO operations and in the commission of a mandate from the president of the Republic, as stipulated in Law 13.491, passed in October of last year, which was initially conceived as a temporary measure to address violent crime during the Olympic Games. But it must be remembered that we are not dealing with homicides committed by the State in a foreign war but in an urban environment against its own population. As it is, residents are warning one another not to go outside without documentation, to carry receipts of the objects they carry, and to use small umbrellas rather than long ones which could be confused for firearms.

“We need a coherent discourse not against any individual’s actions, but to defend the rights of the favela. We cannot curtail anyone’s right to come and go,” said Itamar Silva, a resident and activist from Santa Marta and director of the well-respected NGO iBase, during an event organized by the Federation of Favela Residents’ Associations of Rio de Janeiro (FAFERJ). In response to a comment that there are those within favelas who are in favor of intervention, he puts the challenge to favela activists: “How do I talk with my neighbor who I grew up with? What will be the narrative that we fight for on our land?” The answer seems to be a series of actions presented at the end of the event, which include raising awareness and spreading information among the population via local assemblies and through the work of community communicators. Other suggestions included legal opposition to the intervention with the help of public defenders, including fighting collective warrants and forming a commission to dialogue with the federal appointee, and turning the UPPs into Public Policy Units.

While some residents celebrate the federal government’s energetic response to violence they know all to well, many are skeptical, not only about who is being protected, but also with regards to the cost-benefit of these campaigns. FAFERJ argues the costs of the military intervention should be reinvested in the form of “schools and daycare, hospitals, initiatives for creating jobs and revenue, and social policy geared towards youth,” which the group has dubbed social intervention. This is especially important if we consider that the 14 months in which the army occupied Maré cost public coffers R$600 million, while investment in social programs in the same community over a six year period was only half that, at R$300 million. “We need an intervention that brings us life, not death,” says FAFERJ’s official statement. “This is all for the English to see. After the elections they’re quick to leave. They don’t need any intervention to enter our houses and shoot at our children, the police already do that,” said a resident of Complexo do Alemão who preferred to remain anonymous.

Initiatives are being formed to monitor the armed forces’ actions and prevent rights violations, such as the Intervention Observatory at the Center for Security and Citizenship Studies (CESec), the Legal Observatory at Rio’s Brazilian Bar Association (OAB-RJ), and the Legislative Observatory of the Federal Intervention in the State of Rio’s Public Security Office (OLERJ), formed by the president of the lower house of Congress, Rodrigo Maia, in order to guarantee the transparency of data from each military action in the context of the intervention. With the latter, however, there is concern about the impartiality with which violations will be denounced, since there will be no external body beyond a group of federal agents. What’s more, the observatory’s creation has preceded a more urgent step—the presentation of substantive plans for the intervention.

Impact on politics and elections

The federal intervention seems to be the next big thing in public security given the failure of the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs). Other states in the country are also struggling with significant security challenges, including on Brazil’s borders where the use of the armed forces is justified in controlling the entry of weapons and drugs. However, the choice to implement the intervention in Rio can be attributed to the state’s history of big public security projects, some of which have included the participation of the armed forces, and Rio’s national and international visibility.

For President Temer, who faces particularly low approval ratings, the production of a threat and the subsequent offer of an energetic response to what is seen as one of the country’s main problems, public security, is a daring maneuver that will produce him legitimacy among some. In addition, it diverts attention from his government’s pet project, pension reform (which, unlike a military intervention, is extremely unpopular), while creating a legal mechanism that will allow the reform to be approved quickly. That is because no amendments to the Constitution can be voted on while a state is experiencing military intervention. But Temer has declared that he will suspend the decree of intervention to allow for a vote on pension reform (although in practice it will continue to operate under a GLO). If the reform is approved, he will decree a new intervention. All this gives him time to build support for his measure and the power to render unfeasible any resistance to it once approved. Finally, the military response may have the effect of allowing the candidate supported by his current government to win the votes of Jair Bolsonaro’s potential electorate by assuming a similar center-right agenda in defense of law and order.

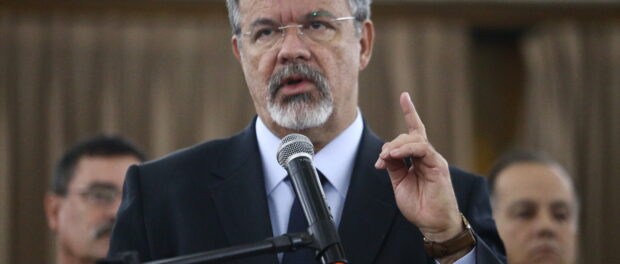

Also at the federal level, the intervention has already led to the creation of the Ministry of Public Security, under the direction of Raul Jungmann who had been the Minister of Defense until these changes. Jungmann headed the military actions in Rio in 2017 and spearheaded an integrated public security plan, which should have been implemented earlier this month but never materialized. The newly created ministry will be responsible for integrating the public security forces and for the Federal Police, Federal Highway Police, National Penitentiary Department, and National Secretariat of Public Security, which had previously fallen under the domain of the Ministry of Justice. As such, it will not overlap with the work of the State Security Secretariats, responsible for the Military and Civil Police. General Joaquim Silva e Luna will occupy the post that Jungmann leaves vacant in the Ministry of Defense, marking the first time a military officer has taken over the Ministry since its creation in 1999.

Rio’s also unpopular state governor, Pezão, who had been responsible for public security policies in Rio de Janeiro, gave up his public security responsibilities through the decree, delegating them to the army in the hope that it will produce quick results. In the short term, the intervention will shift attention away from his administration’s mismanagement and restore governance, and in the long run it could ensure his re-election. There are also rumors that Jungmann himself intends to run for state government. The success of the intervention would strengthen his candidacy.

Finally, Mayor Marcelo Crivella, whose public security policy has thus far concentrated on the city’s beachfront areas, was in Europe to seek security technologies (a mission that failed) at the moment the intervention was declared and did not attend the meeting to create OLERJ. Yet he may also reap the rewards of growth in the superficial sense of security, felt especially in Rio’s wealthiest neighborhoods. The intervention, however, is not only for the city of Rio, but for the state of Rio as a whole. This means that, while military action in more affluent parts may merely shift criminal activity to other municipalities as the UPPs did, there is potential for abusive military action in regions beyond the public eye, places the media do not keep an eye on. These two consequences have the potential to most cruelly impact municipalities like those of the Baixada Fluminense and São Gonçalo outside of Rio, which already count exceptionally high homicide rates.

This is the third article in an ongoing series on the Brazilian electoral political scene in 2018.