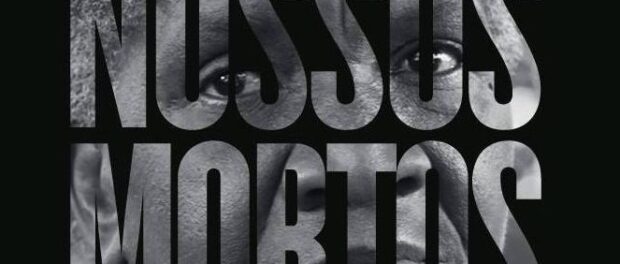

In late March 2005, state Military Police gunned down 29 people in the neighborhoods of Queimados and Nova Iguaçu, in the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan region of Baixada Fluminense, in what would later become known as the Baixada Massacre, the bloodiest in Rio de Janeiro’s history. Thirteen years later, on the evening of March 27, crowds packed Lapa’s Cine Odeon in anticipation of the new documentary “Nossos Mortos Têm Voz” (Our Dead Have a Voice). The film, now in pre-release, follows six Baixada women—all mothers or sisters of victims of police violence—and their efforts to keep their loved ones’ memories alive.

The screening event itself, though focused on state violence in the Baixada region, paid homage to those who had lost family members to violence throughout Rio de Janeiro. As audience members took their seats, each found the name of a victim of state violence in Rio attached to their headrest.

Many of those victims’ family members were present at the event. They took to the stage, standing side by side in solidarity, one by one reciting the names of their lost ones as the audience responded with “presente”—present.

Organizers paid special homage to the recently murdered city councillor Marielle Franco and her driver Anderson Gomes, airing Franco’s 2016 campaign video and reminding the audience that no arrests have been made since her assassination on March 14.

With their film “Nossos Mortos Têm Voz,” directors Fernando Sousa and Gabriel Barbosa of Quiprocó Films hope to give strength to those combating state violence in the Baixada region. Sousa says though all of Rio suffers from state-sponsored violence, the Baixada deserves special attention. “State violence in the Baixada Fluminense features a specific configuration, in that extermination groups and death squads join together with local authorities, be it with the legislative, executive, or judiciary.”

To that end, the film uses the Baixada Massacre as an example of state cooperation in violence, and “as a frame of reference to take on other cases of state violence in the region.” Sousa and Barbosa argue that the violence committed by today’s militia groups—armed off-duty state agents—traces its history to the 1950s, when death squads acted openly in the Baixada. Since then, such groups have only grown in their power and organization.

An estimated 2 million people in 202 neighborhoods throughout the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro live under some form of militia control, and Sousa is right to point out that the Baixada area is especially vulnerable. According to sociologist José Cláudio Alves, of the Baixada’s thirteen municipalities, nine suffer from militia activity.

Militia homicides and extortion are only made worse by frequent police complicity. Just last month, investigators apprehended nine suspected militia members in the Baixada municipality of Mesquita, four of whom were active members of the state’s Military Police.

One of the film’s protagonists, Luciene Silva, was also present at the evening’s pre-screening event. For Silva, who lost her son Rafael in the 2005 Baixada Massacre, this level of police involvement makes victims in the Baixada even less likely to speak out than in the rest of Rio de Janeiro. “People are scared of speaking out, of denouncing the violence. And the violence gets worse and worse,” says Silva. “Many [victims] disappear, they don’t even become statistics.”

This fear of reporting breeds impunity in a system already rife with juridical irregularity. “These police that participate in death squads, they commit these crimes and continue to walk around freely,” says Sousa. He reminded the audience of the case of Joanna D’Arc Mendes: in 2004, three police officers murdered her son Flávio Mendes Pontes in Itaguaí. One officer had his charges thrown out, while the other two went on to participate in the Baixada Massacre one year later.

In supporting the Baixada’s mothers and sisters in their quest for justice, directors Sousa and Barbosa know they fight an uphill battle. “You can be sure,” says Sousa, “we know that this film won’t make millions. We’ve made a public commitment… We’re going to remain involved in all of this.”