This is the second article in a two-part series reviewing the book ‘Social Sustainability, Climate Resilience and Community-Based Urban Development: What About the People?‘ by Cathy Baldwin (University of Oxford) and Robin King (World Resources Institute), and how it informs thinking about Rio’s favelas. Read part 1 here.

What About the People? The Socially Sustainable, Resilient Community and Urban Development leaves it clear that the built environment has great impact on the social sustainability* of a community, as discussed in the first article in this series. This article focuses specifically on the tools presented by the authors that could be useful for leaders in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas looking to make interventions in their built and social environment.

Drawing on research in North and South America, Africa, Europe, Asia, and Australia, Cathy Baldwin and Robin King outline four stages of socially-aware planning practices for urban development: 1) scheme conception, 2) research and community participation, 3) design decisions and implementation, and 4) monitoring and evaluation. The authors describe these stages as they would apply in a formal process of development, started by outside planners, which is often not how development unfolds in favelas where residents take a leading role. However, the principles of the four stages remain relevant for local leaders as they seek broader engagement from their communities in their projects.

Stage 1: Scheme conception

Plans based on expert-driven and technological approaches rather than the ideas of the people they aim to serve often ignore local social and cultural contexts and fail as a result. These approaches also often fall into the trap of overlooking community assets, which then fall victim as projects are implemented without considering or building on those assets. The authors thus argue that social dimensions must be incorporated from the conception stage, exploring specific local social resources, capacities, and organizational conditions. This is essential to comprehend how to overcome local challenges, to set clear social objectives, and to avoid unintended negative impacts on people’s lives. Wrong decisions can negatively impact existing community networks, affecting local social organization and engagement.

Stage 2: Research and community participation

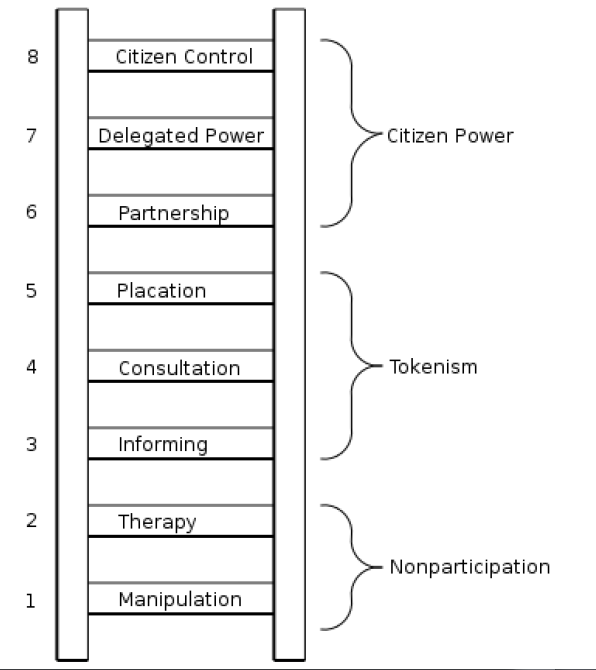

For the work of outside planners, community participation is crucial because residents offer local knowledge that is critical for developing plans. At minimum, planners should be prepared to seek out and incorporate input from the community and to promote civic activities to strengthen a community’s sense of ownership. A democratic and participatory development process built on trust, transparency, and communication is important to ensure popular engagement.

Beyond just a superficial knowledge of local context, it is also necessary to develop a project that respects symbolic dimensions—local cultural and social meanings. Thus, planners should act together with social researchers to use an appropriate method for planning. And in the case of Rio, one would argue that favela-based researchers and residents are the most appropriate partners in this process.

Although social diversity can represent a challenge for planning, it can also offer a diverse range of social resources to support communities through crisis situations and local issues. It is important to embrace all kinds of diversity, thinking about spatial conditions that improve access and safety for everyone, especially minorities, in order to achieve urban equality. Demographic research combined with community participation can, for example, provide knowledge of the population characteristics and the existing state of social cohesion in a community in order to think of ways to build social capital* and cohesion* to create or strengthen community spirit.

Although social diversity can represent a challenge for planning, it can also offer a diverse range of social resources to support communities through crisis situations and local issues. It is important to embrace all kinds of diversity, thinking about spatial conditions that improve access and safety for everyone, especially minorities, in order to achieve urban equality. Demographic research combined with community participation can, for example, provide knowledge of the population characteristics and the existing state of social cohesion in a community in order to think of ways to build social capital* and cohesion* to create or strengthen community spirit.

One of the tools presented for the research and community participation stage is the mapping of cultural meanings of the urban space. Previously done in Belfast, Northern Ireland, a city notably divided by many years of conflict between Protestants and Catholics, the mapping of cultural and social meanings of the landscape and the memories it evokes allows community members to understand their histories and development better. The process of engaging residents to think about the past and how it has contributed to the present can bring a better understanding of the community itself and help residents think about what can be done in the present to create a better future.

The same mapping exercise also allows for identifying community assets, social resources, needs, or weaknesses. One approach to this exercise is through a participatory workshop. Residents are asked to identify and write down on sticky notes the positive and negative aspects of their community, what works well and what could be better. The workshop organizer pins the sticky notes on a board, either on a map or organized by subject. Later the organizer promotes a discussion about everything that was written, prompting residents to talk about the reasons why they wrote each point down and how each aspect can be improved. This process helps residents learn more about their communities and think about what they want for the future.

Community leaders may take advantage of the process and the discussions to start a co-design project. In co-design projects, neighborhood leaders and residents, designers, and government officials work together to identify and meet the needs of a community. Residents can participate in the design and construction processes to build social capital, strengthen collective capacity, and develop pride and ownership. Residents can vote on design decisions for buildings or public places, like placement, layout, and form. Any resident can help with construction through tasks that do not require specific training or ability, although with many favela residents having built their own homes, construction expertise is not in short supply. These methodologies contribute to creating a sense of pride and belonging to the neighborhood.

Stage 3: Design decisions and implementation

Design decisions have to be adapted to the local social and cultural environment rather than simply to financial requirements. When thinking of design solutions planners should keep in mind that a mixed neighborhood and mixed land use are most likely to create an environmentally and socially sustainable* community.

One important design goal is to incorporate open public spaces where all social groups can interact and create a positive community spirit. Social spaces are fundamental to the development of social capital and cohesion because they can promote inclusion and a feeling of trust and safety.

These spaces can be proposed in all types of projects. For example, urgent crisis housing in cases of natural disasters can provide a spatial solution that keeps communities together in new settlements, maintaining their self-organization and social relations. But, it is important to highlight that relocation should be minimized as much as possible and only proposed in extreme and urgent situations, such as natural disasters. Another good example is transport stations. Although usually thought of as primarily serving a utilitarian function, transport hubs can also offer spaces for social interaction as large numbers of people pass through them each day.

Another important measure to guarantee diversity and equity is the provision of affordable housing in city centers. As we can see in Rio and so many other cities around the world, there is a growing trend for low-income people to be pushed out to peripheral regions, making their access to infrastructure and opportunities more difficult and hindering opportunities for democratic engagement.

Stage 4: Monitoring and evaluation

Finally, after designing and implementing a development plan in partnership with a community, it is necessary to have a regular method of monitoring and evaluating its impacts to ensure social and urban sustainability. The community is a fundamental element in the continuity of development processes. When people have a sense of responsibility over their place, as so many of Rio’s favela residents do, they will monitor and evaluate the results of development projects themselves, constantly proposing and initiating new ideas and improvements, regardless of whether institutional support exists or not.

Conclusion

Community participation in local projects helps create bonds and attachment among neighbors, increasing collective capacity. Incorporating these tools and methodologies into the work done by community organizations in favelas, or consolidating them in cases where they already exist, has the potential to increase residents’ agency over their environment, community, and future.

*Glossary

Community resilience: The existence, development, and engagement of community resources by community members to thrive in an environment characterized by change, uncertainty, unpredictability, and surprise.

Social capital: A key factor in building a sustainable community, social capital is the group of benefits that come from consistent social norms and trust built through regular interaction within a community.

- Bonding Social Capital: social capital within a community.

- Horizontal Social Capital: social capital across a network of communities.

Social cohesion: When people from the same community or society get along, trust each other, and live peacefully together with or without social or ethnic differences, supported by economic equality and inclusion, democracy, people having their basic needs met, and social solidarity.

Socially sustainable: When the neighborhood supports individual and collective wellbeing.

This is the second article in a two-part series reviewing the book ‘Social Sustainability, Climate Resilience and Community-Based Urban Development: What About the People?‘ by Cathy Baldwin (University of Oxford) and Robin King (World Resources Institute), and how it informs thinking about Rio’s favelas. Read part 1 here.