For original article in Portuguese published in BBC Brasil click here.

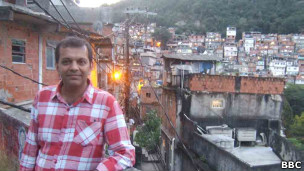

On the elevator on his way up to Morro do Cantagalo, a favela wedged between Copacabana and Ipanema, the Indian writer Suketu Mehta marvels at the new ease-of-access and predicts that “in five or ten years many residents will no longer be able to afford the rent here.”

Mehta has seen the same thing happen in slums of Mumbai, where he grew up before leaving in his teens to live in the US. He returned 20 years later to find “a divided city.” The impressions of that return provided inspiration for his book Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found.

Cantagalo has a new elevator to make it easier to get into as well as increased security following its pacification, and Mehta believes that prices are going to increase, especially considering the view out to the ocean.

“The threat to residents here will no longer come from drug traffickers but rather from the real estate market.”

Mehta was in Cantagalo last Wednesday for the first time, having spent a week last December visiting other favelas in Rio as part of research for an essay on informal settlements in metropolises that he wrote as the introduction to photographer Robert Polidori’s book.

This time, he has come to Brazil to participate in FLIP, the International Literary Festival of Paraty, and then on to Cantagalo to speak to the community about his work as part of the Pacified Communities Literature Festival, also known as FLUPP.

En route to his talk, Mehta took a look at some of the community with BBC Brasil and commented on the similarities with the informal settlements in his own country.

“Actually I think that this would be quite a good settlement in Mumbai. Any resident of a slum there would be happy if their grandmother were able to move to a place like this,” he said.

Same alleyways, same smell

The writer saw the same sort of ditches, open sewers and uncollected rubbish in communal areas and wastelands in Cantagalo as he sees in the Mumbai informal settlements.

He saw the same crooked and narrow alleyways. He smelt the same smells of food being cooked and he heard the TVs blaring out at full volume. He noticed the intense wiring on the electric poles and the sneakers hanging from the wires by their laces.

“I always asked myself about those flying sneakers,” he said, looking up. And he also saw the kites made by kids sailing above the rooftops.

“That really made my heart skip a beat. When I was a young boy I also flew kites in Mumbai.”

But Mehta is also aware of the differences: in Mumbai the landscape is much flatter and the communities more densely populated. Socially there are also differences: in an Indian slum, for example, the doors would all be open and the kids would be running around, going in and out of neighbors’ houses.

And he also spoke of the principal visible difference in Rio, and one that is only relevant to a handful of its hundreds of favelas: the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs). Mehta is sure that the world is keeping close tabs on whether they work out for the better or not.

The economics of trafficking

There was police presence right at the favela entrance. On the walk around, at a newfound viewpoint (with an impressive view to both the ocean and to another favela, Pavão-Pavãozinho, and the multitude of houses on its hillsides), there were many more police on duty.

Mehta wanted to speak with one of them and he asked if all the traffickers had already gone and if residents’ attitude had changed towards the police.

They told him that trafficking is not like it used to be, but that there are still “one or two” remaining traffickers who are the target of daily police action. They also told him that the police are trying to deal with the related issues as trafficking was so ingrained in the communities, and that there is still resistance from some residents as many of them used to survive – directly or indirectly – from trafficking.

Mehta says that “The policeman raises a key point: the economics of the favelas has been based on trafficking, and many generations of residents relied on it for survival. What alternatives are these people going to have? If they are not educated then where are they going to get work?” He also points out the need for professionalization programs and help to get into the job market.

The writer notes that the UPPs do not so much “pacify” than they “legalize” through regulating services and insisting on proper documentation of residents.

‘Cosmetic’ action

Mehta raises doubts about the scope of the program: the official aim is to have 40 UPPs by 2014 even though there are more than 600 favelas in Rio.

“Clearly what is happening is to some extent just cosmetic. It covers areas that are popular with tourists that need to be cleaned up. In the other favelas it is still each man for himself.”

Nonetheless, in December Mehta visited pacified communities – such as Dona Marta and Rocinha – as well as non-pacified, like the Complexo da Maré. The differences were pretty striking.

“To begin with, in pacified favelas you do not see 12-year-old kids walking round with AK-47s, which shocked me in other favelas. I like what is happening here. People are no longer living with the humiliation of a group of kids telling them when they can leave their house.”

Poverty might be more evident in Mumbai’s slums, but violence is much more present in Rio. Now, according to Mehta, in pacified communities those people who have never known what it is to be able to live in safety and security can now do so.

“But one tyranny cannot be changed for another. The police must be careful not to become another occupying force”, he concludes.