For the original article by Francisco Valdean in Portuguese published by O Cotidiano click here.

On July 25th, residents living at the summit of the Santa Marta favela, known as “Pico do Morro” (or “Hill’s Peak”), gathered to listen to a presentation by engineer Mauricio Campos dos Santos, discussing the physical geology of where they live.

On July 25th, residents living at the summit of the Santa Marta favela, known as “Pico do Morro” (or “Hill’s Peak”), gathered to listen to a presentation by engineer Mauricio Campos dos Santos, discussing the physical geology of where they live.

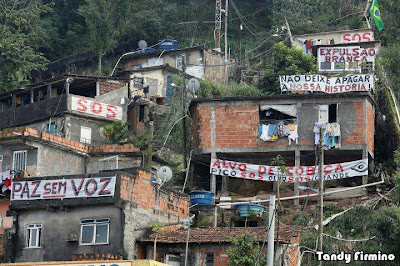

Resisting for over two years, most residents of Hill’s Peak want to remain in the location where they were born and where they have survived the more difficult moments of favela life. The site hosts one of the most beautiful views in Rio de Janeiro and today is considered a privileged place to live by the community. After the installation of the funicular tram, residents can now return home from shopping, or with bicycles and furniture. Paving of the street Seabra Fagundes has also allowed access to the favela from the Laranjeiras side. After installation of the Police Pacification Unit (UPP) in a building that was once the nursery, life has been much easier. Consequently, residents do not want to leave their homes in exchange for the state-offered apartment of 37m ².

As a means to justify the removals of approximately 150 residents who live at the summit, the state is claiming that they live in a (geologically) risky area. It is therefore necessary they be removed, they say. However, residents have counter-argued, saying that following the criteria presented by the technical person from GEO-Rio (which visited the favela in early July), “all of Santa Marta is a risk area.” So if the danger stems from the top of the hill, it poses a threat to all who are below. Therefore, something must be done to avoid a potential disaster. In one way or another, the work to contain this area of the favela must be completed. Locals also point out that in more than its 80 years of existence, Hill’s Peak has never suffered any accidents resulting in death, despite the state’s abandonment of the area. The houses that fell did so due to their old and fragile conditions as at the time they were made of wood, stucco, etc. The landslides that did devastate Santa Marta, which occurred in 1966/67 and 1988, caused the deaths of several residents. However, they all occurred at the dump. Following these disasters, the state undertook a well-done project to contain the area, which has even permitted them to build a set of buildings. This proves there is no ‘risk area’ in Santa Marta that cannot be contained.

Some say that it is very expensive to do works to contain the hillside in Santa Marta. Therefore, evictions in certain areas seem to be the only feasible option. However, this argument needs much more clarification. First because there is no clear verdict on what should be done in this area regarding its containment. A huge amount of money and time have already been invested here since 1988 (the construction of preventative channels and some containment measures). It is necessary to complete the work that has begun. Second, the cost of this undertaking and investment remain unclear. How much are we talking about? Knowing these figures is vital to compare with the construction of a set of buildings on the side of the hill, in an area not suited for such projects. Furthermore, it is important to take into account the views of residents in deciding where resources should be spent.

At a time when Santa Marta is gaining national and international visibility as a place of successful government intervention, there has been a greater concern in catering to tourists than to residents. The information circulating in the favela is that the area will be transformed into an ecological park. Others say that Eike Batista wants to build a hotel on the scenic peak point in Santa Marta. Further views are split and divided in the community, none of them seeming to benefit the people who live there. The Santa Marta community has become a place to make money with “events.” However, it is necessary to preserve the hill for the use and benefit of residents. The struggle of Pico is a struggle of all residents in Santa Marta. The community is among a small number in Rio de Janeiro that has not expanded its territory in the last 20 years, and has managed to maintain a steady population size. As a prize for this success, the community is in danger of seeing its territory diminished. This may be only the beginning. Residents must resist.

— Post by Itamar Silva, Ashoka Fellow and founder of Grupo Eco