Over the course of the week, RioOnWatch will be publishing a series of notes on the tragic fire that destroyed the National Museum this past Sunday. The following note is based on one posted on Facebook by Bryan McCann.

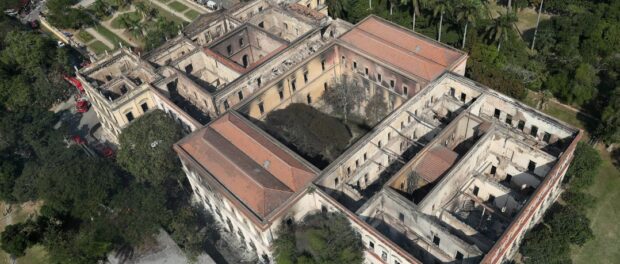

Like everyone interested in Brazil, history, or museums, I remain saddened and infuriated by the National Museum fire. So many have spoken eloquently about what the loss means for Brazil (Theresa Williamson, Cecilia Azevedo, Edésio Fernandes, Rafael Soares Gonçalves, Mario Brum, to name a few…). Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s reflections have the combination of rage, sorrow, and insight that seems appropriate.

I can’t add much to that except my own relatively minor personal experience, and thoughts of the contributions of an illustrious colleague. In 2006-2007 I spent several weeks conducting research at the Social Anthropology Library at the National Museum. I took the metro to the São Cristóvão station (always jam-packed, as it is a transfer point for the metro and commuter rail), crossed over the railroad tracks on the pedestrian bridge, passed through the wrought-iron gates and entered the parkland of the Quinta da Boa Vista—an instant transition from one of Rio’s most hectic junctions to one of its most serene reserves. More often than not, a group of schoolchildren on a class trip to the museum was on the same trajectory. As they rushed toward the main entrance, I headed around to the back, to the Anthropology Library.

I would spend the day reading the theses and dissertations produced in the Social Anthropology Program in the late 1970s and early 1980s when that program was one of many nodes of a redemocratizing Brazil discovering and documenting its own plurality, and pressing for expanded citizenship. It was no coincidence that the same program produced some of the best theses on favelas of Rio de Janeiro and indigenous populations of distant Acre. It was all part of the same wave of hopeful, committed research—scholarship as citizenship. Those theses were part of a library of tens of thousands of volumes, most of them rare, some of them unique. All now lost in the fire, to my knowledge. In theory, those theses should be among the easiest things to replace after the fire, right? In theory, only, I am afraid, as in many cases there will be no other existing copies.

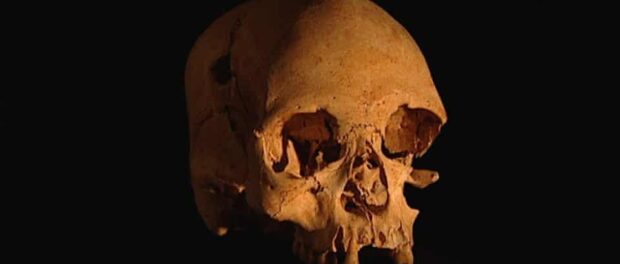

Most of what has been lost is completely irreplaceable, like the 12,000-year-old skull of Luzia, found in a cave outside Belo Horizonte in the 1970s. Poor Luzia has died a second time, victim of abusive neglect.

On my most recent trip to Rio, in July of this year, I had the honor of being part of a Brazilian Studies Association (BRASA) committee presenting the Lifetime Contribution Award to Anthony Seeger, for his long and distinguished career in the service of Brazilian Studies in both Brazil and the US. Among his many achievements, Anthony was director of the Graduate Program in Social Anthropology at the National Museum in 1981-1982, a key part of that wave of pioneering research. We celebrated Anthony Seeger and the influence of that program, including all it has done to demonstrate that indigenous Brazil is not merely part of a frozen past but a vital part of a contested present.

How sad to think that the next researchers to make their way to Rio will not be visiting the library at the National Museum. It is difficult to imagine it ever opening again, in anything like the same form. And the schoolchildren will not be visiting the museum. And the work that we were celebrating only six weeks ago as one of the foundations of Brazilian higher education and Brazilian Studies now lies in ruins. The National Museum brought together all these disparate threads, and they are now severed.

So much is irreparably lost. The connections, or at least the shared interests—between schoolchildren, researchers past and present, all the varied people who crisscross the Quinta da Boa Vista—can perhaps be reconstructed, even though so much about Brazil’s current political situation tends to destroy or obstruct such connections and shared interests. By severing those connections, the fire both destroys and atomizes, fostering isolation instead of shared interests. Brazil has constructed citizenship from the ashes before. I’ll hope that it can do so again.

Bryan McCann is a professor of Brazilian history at Georgetown University. McCann served as president of the Brazilian Studies Association from 2016-2018. His recent book, Hard Times in the Marvelous City: From Dictatorship to Democracy in the Favelas of Rio de Janeiro (Duke, 2013) explores the political relationship between Rio’s favelas and municipal and state government. McCann currently serves on the board of Catalytic Communities, the organization that publishes RioOnWatch.