Over the course of the week, RioOnWatch will be publishing a series of notes on the tragic fire that destroyed the National Museum this past Sunday. The following note is based on one posted on Facebook by Léo Custódio.

Our family was in Magé—my hometown in the Baixada Fluminense—having a normally joyful and relaxed Sunday barbecue when a friend rushed outside. “The National Museum is on fire!” she shouted repeatedly. Instead of their typical serenity, her eyes were horrified. Her smile was gone.

Concern spread among us as the flames burned some of Brazil’s most important historical records. It felt like they were burning a lifetime of memories, along with my future plans.

Let me give you a bit of context that the media probably will not emphasize: a description of what the fire means to people who grew up in the North Zone and Baixada Fluminense—predominantly black and brown, low-income areas in the Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro.

The museum was located in São Cristóvão. The neighborhood is in the north of the city. Most people who live in the region are low-income workers. Due to the historical neglect of the North Zone, the region is not generally considered very safe to stroll around in. For this reason, Quinta da Boa Vista—the park where the Museum was located—is one of the few remaining public spaces in which low-income people of the North Zone feel genuinely comfortable, without the sense of not belonging that many feel in the fancy, beachside South Zone.

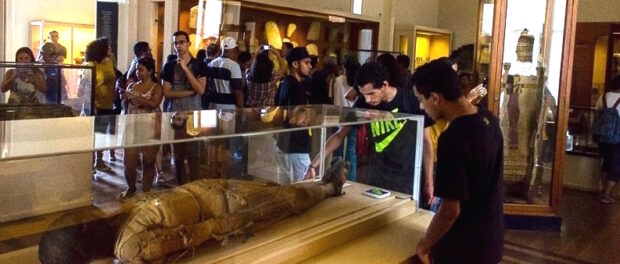

Unsurprisingly, most of the times I was there hanging out at the park, I was predominantly surrounded by black and brown people—families having picnics in the park or visiting the zoo, children running free and giggling on the grass, youngsters dressed in public school uniforms passing their free time…

Therefore, unsurprisingly, I’d dare to say that the National Museum was the most accessible (in all senses) to black and brown low-income families. I never saw so many people like me in any other museum as I saw there. It felt comfortable to be at the Museum, despite the uncomfortable heat of some rooms.

All of this is to say that beyond the horrible historical loss, the fire is another deadly blow to cultural life in the North Zone. There are fewer and fewer public spaces for low-income workers as the years go on.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my 10-year-old nephew and how sad it is that so many free and affordable cultural activities that I had as a child will not be available to him. Here in my hometown, some adults and I had been planning on taking the kids to Quinta da Boa Vista. That trip would have included a visit to the National Museum, just like others took us when we were kids.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my 10-year-old nephew and how sad it is that so many free and affordable cultural activities that I had as a child will not be available to him. Here in my hometown, some adults and I had been planning on taking the kids to Quinta da Boa Vista. That trip would have included a visit to the National Museum, just like others took us when we were kids.

Decades-long government neglect caused the fire—not only Brazil’s well-known neglect of culture and history but specifically a certain deliberate neglect of public spaces where low-income workers from Rio’s North Zone feel good.

Dr. Leonardo Custódio is a researcher at the University of Tampere, Finland and originally from Magé, a municipality in metropolitan Rio de Janeiro (@_LeoCustodio_).