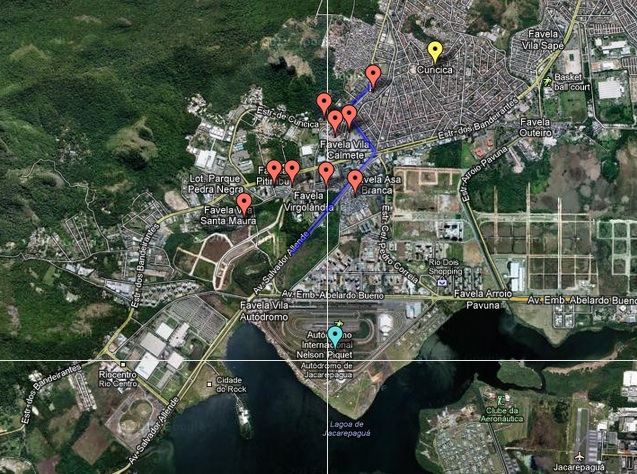

This is the third of four articles about the cluster of favelas in Curicica, Jacarepaguá, that are awaiting urban integration projects through the Morar Carioca upgrading program.

Quando será? (When will it be?)

The Residents’ Association of Vila Calmete sits above polluted waters that run alongside the community’s residential streets. On the other side of a short bridge, rich plantlife springs out of diverse pots of soil, framing the river through its length: a stark juxtaposition that accents both the potentials and the limits of community capacity absent public provisions. “None of this was here when I first visited Vila Calmete,” said Bezerra, president of the neighboring Asa Branca. “Tilzé made this community beautiful. But people still want better.”

José da Cruz, or Tilzé, isn’t the type one would imagine to spearhead a community-wide gardening project. The air he carries is stern and initially intimidating, his talk pointed and frank, often bitingly cynical. A trace of fatigue cradles his eyes and his voice – though this does nothing to hinder his contributions to the community where he resides. As part of the Community Council of Public Security’s ethics board for 9 years and president of Vila Calmete for 8, he’s dealt with many of the issues facing Curicica’s favelas, and has run again and again into the constraints that limit community action.

“The communities here have been abandoned, and mine among them,” he said. “There’s no basic sanitation, no legalized water. And when all you have is a community leader and a board of directors, there’s no force. There are limits to what you can change.” Sitting in a shaded square next to the Resident’s Association where martial arts lessons are held for the community’s youth, he described past projects that dissolved due to lack of space, and the difficulty in organizing residents who are already busy working to sustain their own families.

“The communities here have been abandoned, and mine among them,” he said. “There’s no basic sanitation, no legalized water. And when all you have is a community leader and a board of directors, there’s no force. There are limits to what you can change.” Sitting in a shaded square next to the Resident’s Association where martial arts lessons are held for the community’s youth, he described past projects that dissolved due to lack of space, and the difficulty in organizing residents who are already busy working to sustain their own families.

“We’ve been told that Morar Carioca will be coming in to improve the community,” said Tilzé of the city government’s program to upgrade and integrate all of Rio’s favelas by 2020 through a slew of urban investments. He remains eternally skeptical: “It’s written, at least. But nobody really knows.” With measured irony, he half-sung a line from a tune by Rio-born artist Zé Rodrix: “Quando será, quando será o dia da minha sorte?” (“When, oh, when will be my lucky day?”)

“Another name for Favela-Bairro.”

“The only thing that the Prefeitura (city government) has done here,” said Tilzé, “was a daily cleaning of the river that started 3 years ago. But it ended because of politics, a change in the government. That’s really what decides everything. It’s all politics.”

The scarce selection of government investments throughout the history of the favelas around Vila Calmete have been similarly half-hearted. In Vila União de Curicica, a row of houses that faces out of the community used to be connected to Rua Ventura by durable concrete footbridges stretching across a stream that lines an edge of the street. But in an attempt to “open up” the canal, the City government replaced the bridges with meagre wooden substitutes that often break under people’s feet.

“I fell into the stream not too long ago,” said one resident. “Struck my head and landed in the dirty water.” This was far from an isolated incident, as her neighbor, who’d seen it happen too often, informed us. Politicians come in electioneering, she recounted, seeking to gain support, to build a good image through low-commitment, low-impact projects in less privileged communities. The result is ill-informed policy that rarely benefits the community on a genuine level, with little focus on the long-term; in the case of Vila União’s bridges, public attention evaporated as soon as the implementation phase came to a close. “We have to fix their mess ourselves.”

“We can fall in s**t,” she joked bitterly. “Quite literally.”

“As far as I can tell,” said Tilzé, “Morar Carioca is just another name for Favela-Bairro.” In fact it is formally recognized as a continuation of the 1990s-2000s municipal government Favela-Bairro program. Except Morar Carioca is in theory supposed to build on lessons learned, guaranteeing community participation, maintaining architects in the process through the final stages of execution, generating more creative solutions and incorporating environmental sustainability criteria. The idea is to upgrade the favelas, taking resident achievements in the area of construction and community-building and bringing in the necessary public infrastructure to complete their full urbanization and, in the end, achieve “social integration:” a stitching together of the two traditionally disparate sides of the “Cidade Partida” (divided city), as Rio is known.

“As far as I can tell,” said Tilzé, “Morar Carioca is just another name for Favela-Bairro.” In fact it is formally recognized as a continuation of the 1990s-2000s municipal government Favela-Bairro program. Except Morar Carioca is in theory supposed to build on lessons learned, guaranteeing community participation, maintaining architects in the process through the final stages of execution, generating more creative solutions and incorporating environmental sustainability criteria. The idea is to upgrade the favelas, taking resident achievements in the area of construction and community-building and bringing in the necessary public infrastructure to complete their full urbanization and, in the end, achieve “social integration:” a stitching together of the two traditionally disparate sides of the “Cidade Partida” (divided city), as Rio is known.

An earlier article detailed some fundamental flaws in Favela-Bairro that caused an otherwise fruitful program to fall short of its high aims. In short: a focus on physical improvements over a more holistic fostering of equal opportunities, the absence of genuine community participation in deciding the shape of the investments, and the eventual deterioration of public insertions through lack of maintenance.

Though it’s too early to judge how Morar Carioca fares according to these criteria, the tradition of empty politics and unproductive interventions that Curicica’s settlements have experienced to date has left some more cautious than eager. Ivan, a director in the Residents’ Association of Vila Calmete, expressed reservations that “the investments might end as soon as the upcoming election is won.”

“We’ve been waiting.”

The dominant sentiment in Curicica, however, has been one of excitement. In Asa Branca, where public works have already begun through the Secretary of Public Works, rather than Morar Carioca, Association president Bezerra has been in close contact with city government officials. “As far as I see, there’s nothing political behind it,” he said. “They’re really here to make our communities better.”

The dominant sentiment in Curicica, however, has been one of excitement. In Asa Branca, where public works have already begun through the Secretary of Public Works, rather than Morar Carioca, Association president Bezerra has been in close contact with city government officials. “As far as I see, there’s nothing political behind it,” he said. “They’re really here to make our communities better.”

Edson Ribeiro, the president of Vila Pitimbu, is similiarly optimistic. “They’re doing some great work with the Morar Carioca project,” he said. “There’s already been a visit from the Secretary of Housing, and now we’re just waiting for engineers to come, re-register the residents, and organize everything for the upcoming upgrading.”

Having led his community for decades, Ribeiro is proud of the progress and the living necessities that he and his neighbors have accomplished with their own efforts. “But we did it all as residents, with the little technical knowledge we had. We’ve managed to live well here, but it’s still not technically perfect. And now everything will be technically perfect,” he said with cheer.

All the communities I interviewed seemed to agree on their main priorities with the upcoming investments. “Basic sanitation is essential,” said Tilzé, “the first item.” Though some communities have already received sanitation services, the ones who lack are faced with the sights, smells, and eventual health risks that stray trash and dirty water pose. “I don’t smell it anymore, personally,” Tilzé said, gesturing to the river below us, “but people aren’t happy with it.”

And in Vila União, Sônia relayed stories of rats living within walls, cockroaches slipping in for visits, and mosquitoes settling within pockets of stagnant water trapped under trash by the river on Rua Ventura – exploding out in swarms to greet those who pick the garbage out from over them. All the community’s drainage goes into the stream. Forced to work within the limits of their resources, land, and know-how, there aren’t many alternatives. A recent project to connect Asa Branca’s self-made sewer system to the city’s formal network, solving problems of pollution and overflooding in a nearby river, offers hope to surrounding communities dealing with too much waste and too few options.

And in Vila União, Sônia relayed stories of rats living within walls, cockroaches slipping in for visits, and mosquitoes settling within pockets of stagnant water trapped under trash by the river on Rua Ventura – exploding out in swarms to greet those who pick the garbage out from over them. All the community’s drainage goes into the stream. Forced to work within the limits of their resources, land, and know-how, there aren’t many alternatives. A recent project to connect Asa Branca’s self-made sewer system to the city’s formal network, solving problems of pollution and overflooding in a nearby river, offers hope to surrounding communities dealing with too much waste and too few options.

Walking into president Vânia’s office in Vila União, the paper clippings that adorn the wall next to her door include a newspaper article about Vila União wanting to legalize their water services. Tilzé refers to this lack of formal water as a “basic stain” that marks most informal settlements, and president Renildo of Abadiana is similarly eager to see water as a public service rather than a siphoned good. “We’ll have to pay,” he said, “but it’s better like that, I think, to have the product at your door, guaranteed.”

Both Village Campo da Paz and Vila Calmete lamented the lack of recreational spaces for children. “But there are options not too far away,” said Village president Lindinalva da Silva. “It’s a lack, but there are more important things: health, education, and housing.”

The growing population in her community has led to building at precariously high levels by some community members. “The Association only permits a first and a second floor,” she said, “but we have no way to enforce it, and so people build a third floor, and then a fourth. The structure can’t always bear it.” There is a space here for an entity with legal power to enforce building regulations, and to provide alternatives for residents seeking housing. Though daycares are available in the area, Lindinalva also commented that there remains a need for places “for children to stay, sleep, and eat securely” in the absence of their working parents. Once again, hope can be found a block away in Asa Branca, where the Prefeitura has communicated plans to build a school, a daycare, and a medical post on some empty land next to the community.

The growing population in her community has led to building at precariously high levels by some community members. “The Association only permits a first and a second floor,” she said, “but we have no way to enforce it, and so people build a third floor, and then a fourth. The structure can’t always bear it.” There is a space here for an entity with legal power to enforce building regulations, and to provide alternatives for residents seeking housing. Though daycares are available in the area, Lindinalva also commented that there remains a need for places “for children to stay, sleep, and eat securely” in the absence of their working parents. Once again, hope can be found a block away in Asa Branca, where the Prefeitura has communicated plans to build a school, a daycare, and a medical post on some empty land next to the community.

“We’ve been requesting these improvements from the city government for a while,” said Renildo. “We’ve been waiting.” Standing in the main plaza where the majority of his community, Abadiana, rests, he told me his plans to organize the community to “make the square beautiful” in anticipation of the long-awaited projects.

O dia da minha sorte…

A few hours before my colleague and I arrived in Vila União to meet Sônia, workers for Morar Carioca had been circling the community, interviewing residents in preparation for November, when the projects in Curicica are scheduled to start. “They were trying to get a sense of what we wanted to see from the project,” said one resident. “They seemed like good people.”

A few hours before my colleague and I arrived in Vila União to meet Sônia, workers for Morar Carioca had been circling the community, interviewing residents in preparation for November, when the projects in Curicica are scheduled to start. “They were trying to get a sense of what we wanted to see from the project,” said one resident. “They seemed like good people.”

In his living room, Bezerra showed me the letter he had sent in 2009, requesting the presence of public services in his community. He’s grateful for the luck he’s had. Many communities haven’t received a productive response when reaching out to the city government.

For Asa Branca, public works have arrived. Outside, the streets were being gutted to make way for new infrastructure. “They’re opening the road up so they can put it back in better shape,” said Wesley, Bezerra’s nephew. A few onlookers complained about the present state of the street, but many others looked on positively, excited for the improvements that the chaos of drills and bulldozers promised. “Look,” said another resident pridefully, pointing at some community members who had been hired to work on the road. “My neighbors are working to improve the community.”

Tilzé, however, was a little more skeptical. “Once Morar Carioca enters,” he said, “they’ll have to break everything down again. They just like to spend money, to throw money away.” Although he is unwilling to place too much trust in the city government’s plans before they become action, he is not against the principle of what Morar Carioca promises. “These things have to be done from outside,” he said, returning to the question with which we began: “But when?”

This is the third of 4 articles about the cluster of favelas in Curicica, Jacarepaguá, Rio de Janeiro prior to upgrading through the City’s Morar Carioca program. The last article will examine inequality, social perceptions, and the different forces that define the opportunities of those who reside in these communities. And in the end, the forces that sustain them: culture, strength. Love.

Click here to see more photos of the communities featured in this series, or watch the slideshow below: