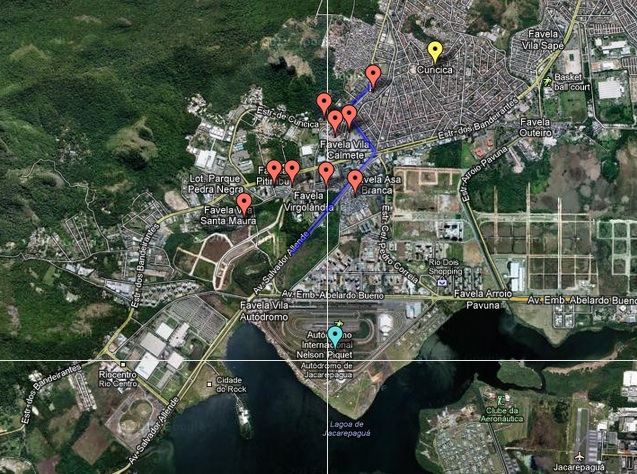

This is the final of four articles about the cluster of favelas in Curicica, Jacarepaguá, that are awaiting urban integration projects through the Morar Carioca upgrading program.

“Life continues.”

“She was in an accident just recently,” said Regina Sônia Gomes Baptista, known by Sônia, ex-president of Vila União da Curicica, as we cut through her friend’s house and into her community. “The car flipped over and she was thrown right out.” Looking at the girl, it would have been hard to guess. Covered to the nose in a wool blanket, the look in her eyes gave away nothing but soft contentness and a shy, amused curiosity about the pair of foreigners who had found themselves in her living room.

“She was in an accident just recently,” said Regina Sônia Gomes Baptista, known by Sônia, ex-president of Vila União da Curicica, as we cut through her friend’s house and into her community. “The car flipped over and she was thrown right out.” Looking at the girl, it would have been hard to guess. Covered to the nose in a wool blanket, the look in her eyes gave away nothing but soft contentness and a shy, amused curiosity about the pair of foreigners who had found themselves in her living room.

“She’s a strong one,” said Sônia, a bit later. “You never know when things like that will happen. But life continues. It has to.”

And so it does for the residents of Curicica’s informal settlements. In some important ways, they’re still caught mid-fall in the momentum of institutional failures that hatched their communities. A tradition of inequality persists across the city, and these individuals continue to live uninvited to many of the conversations that decide their lives. But they continue to live – with soul, with music, with pride of the places and the families they’ve built. Their feet are anchored to the solid ground they’ve discovered amid the storms. The solid ground they hope to keep.

“Forget these little communities.”

Jacarepaguá holds a privileged spot in the hearts of many Brazilians. As home to Globo’s television studio, PROJAC, the largest production center in Latin America, its influence is unmissable. PROJAC’s programming fills screens across the country; its sights and colors spill out from homes and bars and restaurants from dawn til dusk.

Jacarepaguá holds a privileged spot in the hearts of many Brazilians. As home to Globo’s television studio, PROJAC, the largest production center in Latin America, its influence is unmissable. PROJAC’s programming fills screens across the country; its sights and colors spill out from homes and bars and restaurants from dawn til dusk.

“They filmed some of the scenes in (the telenovela) Avenida Brasil here, within the community,” said Sônia, recalling an episode where one of the characters was filmed half-naked in the street, predictably attracting the smirks and whistles of passers-by.

But according to Tilzé, the eye of the media never goes where it would make the best impact. “Globo has never entered the community,” he said, “except to misrepresent it.” What little attention is reserved for Rio’s favelas goes straight to the famous City of God and sprawling Rocinha, plus a handful of other favelas in the South Zone.

“Forget these little communities” is the message that comes across, according to Tilzé, and the sentiment stretches out from televisions screens and into the policies drawn up by the state. “We don’t receive any resources over here,” he said. “They place everything in City of God, as if it were the only community with problems in Jacarepaguá. Those big, well-known communities give the Brazilian government a kind of (PR) return that we can’t. To them, we’re just a waste of time and money.”

“Forget these little communities” is the message that comes across, according to Tilzé, and the sentiment stretches out from televisions screens and into the policies drawn up by the state. “We don’t receive any resources over here,” he said. “They place everything in City of God, as if it were the only community with problems in Jacarepaguá. Those big, well-known communities give the Brazilian government a kind of (PR) return that we can’t. To them, we’re just a waste of time and money.”

“Social discrimination exists, and it exists plenty,” said Sônia. In addition to neglect by the government and the mainstream media, the informal residents of Curicica find themselves on the difficult end of an uneven playing field. “In our schools,” said Ivan, a director of the Residents’ Association of Vila Calmete, “the teachers are ill-paid and a good part of them are new interns. The students don’t end up learning much. With more money, you can supplement your education through tutors and preparatory classes, but we don’t always have that option.”

Sônia told us of a girl in her community who wants to be a dentist, but has to work from day to night to pay for her education, leaving her with scarce time to dedicate to her studies. “She has a lot of passion, but it’s difficult,” she said. University is rarely free, and it’s difficult to compete for scholarships with students from more privileged upbringings. “There are few vacancies and too much need. Children from poverty don’t have opportunity. They end up massacred.”

A real way forward?

Regardless, most of Curicica’s residents appreciate the relative privilege of where their communities are located. “We’re a peaceful community, and I hope it stays that way,” said Lindalva, president of Village Campo da Paz. And Ivan, a resident of Curicica since he moved from the northeast of Brazil two decades ago, told me that he’s “never heard a shot” over the length of his residence. When asked about the relationship between formal neighborhoods and the favela communities of Curicica, Sônia exclaimed: “Beautiful! When the residents of Curicica have a meeting, we’re all invited.”

Curicica’s proximity to the upcoming Olympic Park has also put it on the fast track for the Morar Carioca upgrading project, as discussed in the previous article. Power politics, social discrimination, and the colonial legacy of inequality have been disowned at the explicit level, and decision-makers have opted instead for “inclusion” and “community participation” as their sailing winds.

But patriarchal impulses live and linger between what is said and what is done, between the mythology of “Olympics for all” and the actions chosen by the forces that claim to pursue “social integration.” In examining the city government’s actions, it does help to acknowledge that the government is a heterogeneous body where several, often contradictory impulses are competing for control. In the midst of it, there do exist genuine actors pushing for genuine progress. What has risen from that noise, however, has fallen short. So far.

Until a unified sincerity surfaces, the residents of Curicica will continue to be threatened by the dreadful residuals of unchecked government ambition. Families will be pushed out to make room for Olympic traffic, the will of the people will be ignored for expensive spectacles, and gentrification will accompany the waves of urbanization brought by architects and bulldozers.

Unless, as Tilzé said, “we keep our eyes open.”

“Thank you for the wealth.”

Distant chatter and unhurried movement greeted us, at our exit, into the easy air of nighttime Vila União. Across Rua Esperança, parents were returning from their workday commutes, unwinding to the sound of training wheels pedaled over the cement. Two teenage girls joked as they packed up their popcorn stand – cleaning, disassembling, turning out the light. Another good day’s work.

A young boy sprung out of the adjacent house, and with his exit exploded the bright gold and crimson clothing stored in the far edge of the room inside. “They’re for Carnival,” one of the teenagers said. “I get excited every time I see them.”

When I talk to people from outside the favelas about these informal communities, the same images seem to occupy the forefront of their perceptions: drugs, violence, poverty. And though these images are not without truth, the stories that I encountered in Curicica were in a different vein. When I asked them what it was like to live where they did, the moments they shared were those of dancing forró in the middle of a neighborhood churrasco, of flying kites from the rooftop terrace, of children playing in the shared square that is the residential street. They were about family, culture, and friendship. Trust.

“One protects the other,” said Sônia. That night, she took us to meet Carlos, another resident of Vila União, and though we knew nothing about their personal histories, they seemed like people who understood each other. At the very least, they were people who completed each other’s sentences.

“One protects the other,” said Sônia. That night, she took us to meet Carlos, another resident of Vila União, and though we knew nothing about their personal histories, they seemed like people who understood each other. At the very least, they were people who completed each other’s sentences.

“When I ask for someone’s hand, they help me,” Carlos said. “Even if you don’t see each other, even if you don’t talk a lot, you depend on your neighbor.” Having accompanied Bezerra, president of neighboring Asa Branca, during a good number of his walks, one could see that kind of dynamic between the sibling communities of Curicica. He was always stopping to talk, stopping to listen, to help. “When we have a problem, Bezerra brings his people and we figure it out together,” said Ivan of Vila Calmete. “And we do the same.”

On the question of the perceived “lack” in communities like Vila União, Carlos replied: “This community we’re in isn’t very, very lacking, really.” Though certain conditions needed to improve, he had what he needed. “In the end,” he said, “when we die, the first thing we’re going to do is say thank you for the wealth…”

“There’s a good part of this community that’s evangelical,” said Carlos, “and a lot of what we learn at church is about love.” Sônia nodded knowingly, shivering a little in the cool evening. But her voice kept warm. “Love,” she said, “above all else.”

This is the last of 4 articles about the cluster of favelas in Curicica, Jacarepaguá, Rio de Janeiro prior to upgrading through the City’s Morar Carioca program. Rexy Josh Dorado, RioOnWatch Intern, thanks Curicica, CatComm, and the favelas of Rio for the wealth of experiences as he returns to Brown University in the Fall. He’ll be in touch.

Click here to see more photos of the communities featured in this series, or watch the slideshow below: