Perhaps it was only fitting that an election of unparalleled turbulence—featuring an assassination attempt and a former president campaigning from prison—was nearly decided in the first round of voting with one final and shocking twist. As the vote counts trickled in from every corner of Brazil on the evening of Sunday, October 7, far-right nationalist candidate Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party (PSL) led the field with 46% of valid votes—enough to stun a nation, but not enough to win the presidency outright. Instead, he will proceed to a run-off on October 28 against leftist Workers’ Party (PT) candidate Fernando Haddad.

The Brazilian electoral system can be confusing, particularly for international observers. Why are there two rounds of voting? How are votes counted so quickly? How do these rules affect how elections actually play out?

The design of each democracy’s electoral system sculpts political outcomes in intended and unintended ways. The rules of the system can explicitly swing electoral results—as in the United States, where two of the last three presidents have lost the popular vote. Conversely, the system’s nudges can subtly shape policymaking for years beyond election day. Simple but fundamental elements of elections, such as ballot design, can quietly determine who is empowered and who is undermined.

Brazil’s democracy, like that of the United States, is imperfect. Both countries grapple with representing a vast population with competing priorities, and both are plagued by many of the same invisible hands that shape elections behind the curtain—dark money, corporate interests, and intentionally fake or misleading news, to name a few. However, Brazilian elections feature unique elements to address issues inherent to democracy that are distinct from features of the American electoral system. In this article, we will focus on five key aspects: the multi-party system, the two-round runoff, the compulsory vote, electronic voting, and the highly-regulated nature of political campaigns.

Brazilian Civics 101

Brazil is divided into 26 states and a Federal District (where Brasília, the capital, is located), all of which fall under the jurisdiction of the federal government. The federal government is divided into three branches: the executive branch, headed by the president; the legislative branch, known as the National Congress, which is split into the Senate (81 seats, three for each state plus the Federal District) and the Chamber of Deputies (513 seats, with each state and the Federal District awarded between 8 and 70 seats based on population); and the judicial branch, consisting of the Supreme Court (11 justices) and lower federal courts.

General elections are held every four years. Presidents are limited to two consecutive four-year terms but can run again after allowing for a one-term break. Senators are elected to an eight-year term, while deputies serve a four-year term. Supreme Court justices (known as ministros) are appointed by the President, confirmed by the Senate, and serve until the mandatory retirement age of 75.

1. Multi-Party System and Proportional Representation

Brazilian politics is a highly fragmented, multi-party affair. Following the 2018 elections, representatives of thirty parties were elected to Congress—marking a record high. While certain parties have been highly influential over the past decades, “establishment” parties do not dominate as Democrats or Republicans do in the United States. The potential for prominent parties to dominate is further undermined by the relative ease of creating new parties and the fluidity with which both voters and candidates shift parties. Still, the Workers’ Party (PT)—adored by scores of supporters for instituting social programs that have lifted millions out of poverty, loathed by others for its role in the massive Lava Jato (“Car Wash”) scandal—is the towering giant of contemporary Brazilian politics, having won the past four presidential elections. However, even the PT has never held more than 91 of 513 seats in the Chamber of Deputies or more than 14 of 81 seats in the Senate at one time. Conversely, in the United States, one party has held an absolute majority in either the House and the Senate in nearly every government since the two-party era began in the 1800s. Rather than unilaterally muscling through an agenda, Brazilian parties can only effectively govern (or obstruct) by building coalitions with other parties.

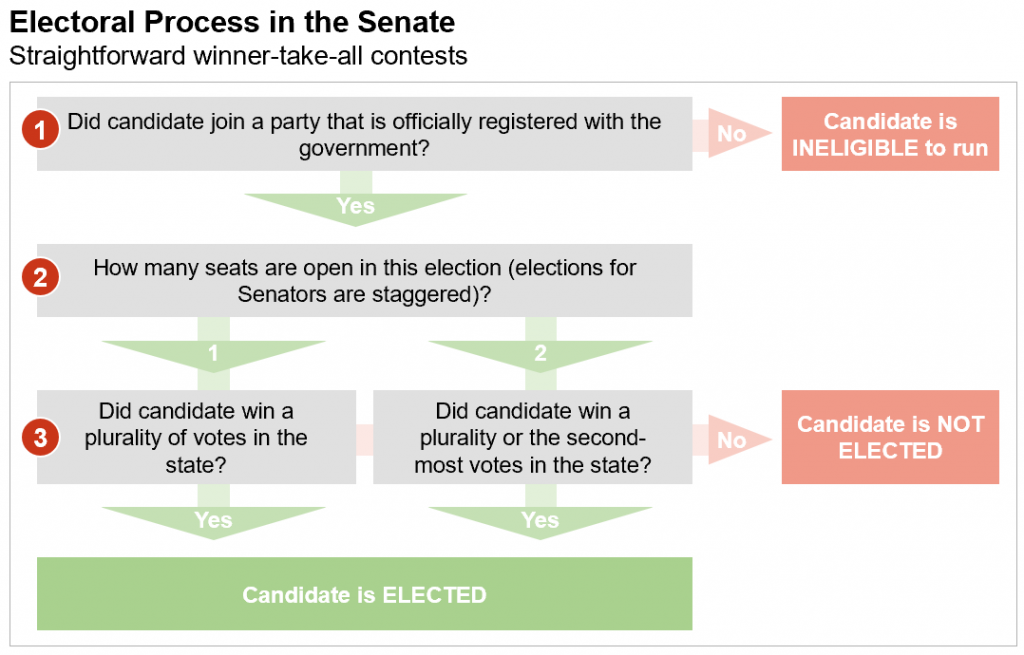

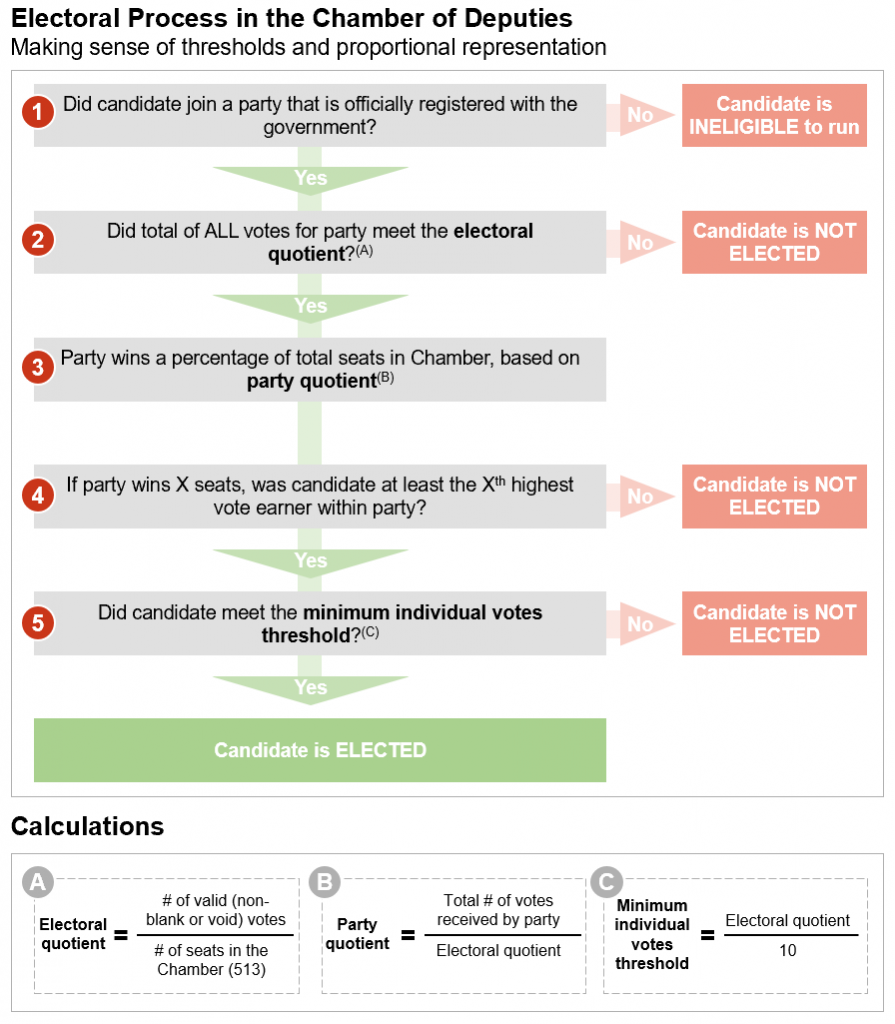

In Brazil, senators are elected in relatively straightforward winner-take-all elections: two seats are available at a time and the top two vote earners are elected. On the other hand, seats in the Chamber of Deputies are awarded based on a remarkably complex system of proportional representation. Only officially registered parties can run candidates and they must meet a threshold of minimum votes, known as the electoral quotient, to be represented at all. This is designed to lock out fringe parties, but also creates a high bar for new or small parties to clear. Second, parties win a proportion of total seats, known as the party quotient, based on the proportion of total votes received by all of the party’s candidates. Finally, parties fill seats with the highest vote-earners within the party, but only if their candidate has cleared another minimum votes threshold—the seat is lost to another party if a candidate doesn’t meet this threshold.

In electing city councilors, state deputies, and federal deputies, voters have the controversial option of the party vote (legenda)—an alternative to casting votes for individual candidates. This can be an appealing option to well-intentioned voters who are simply lost among massive ballots that can feature hundreds of candidates. However, some political analysts and candidates have explicitly implored voters to avoid the party vote; these votes are pooled to calculate the total number of seats earned by each party, but they do not help candidates reach the individual vote threshold. In Sunday’s election, only 27 of 513 federal representatives were elected exclusively via individually-earned votes; the remaining 486 benefited from the “surplus” of votes for those 27 candidates and from the popularity of their respective parties.

Multi-party and proportional representation systems are designed to promote a diverse set of perspectives in government. Additionally, voters for unsuccessful candidates can walk away knowing that their vote will directly impact outcomes—unlike U.S. congressional elections, in which losing by ten votes is the same as losing by ten thousand.

However, making sense of this system has proven a challenge for voters and politicians alike. For voters, a dizzying array of candidates with multiple layers of thresholds and calculations make it difficult to understand where one’s vote is really going. Furthermore, members of Congress are elected to represent their states, not localized districts. Not only are the lengthy state-wide ballots overwhelming, but this also adds to the sense of distance between individual citizens and their government representatives.

For politicians, how one chooses to navigate the multi-party system can be the difference between legislative stalemate and sweeping change—or between life at home or in a prison cell. In the wake of the massive Lava Jato corruption scandal, critics have argued that the difficulty of building consensus in a multi-party system inherently creates a breeding ground for graft. Nearly a decade before Lava Jato, the Mensalão (“Big Monthly Payment”) scandal erupted, leading to the imprisonment of PT leaders convicted of orchestrating the vote-buying scheme. Since proportional representation can make it difficult to directly vote out unpopular or corrupt representatives, enforcing party discipline falls upon the shoulders of party leaders, who may be unwilling or complicit in corruption themselves.

2. Two-Round Runoff

If a presidential candidate does not receive more than 50% of valid votes (excluding blank and null votes—see section three), voters choose between the top two candidates in a second-round run-off held a few weeks after the first round. This often becomes necessary to narrow the field as a crowded field of presidential hopefuls during the first round is another consequence of Brazil’s multi-party system. In the seven elections since the abolition of Brazil’s military dictatorship in 1985, only twice (in 1994 and 1998) has a candidate won outright in the first round. Following Sunday’s first round of voting, Bolsonaro fell just short of this threshold, prompting a second round.

Two-round elections are designed to ensure that the winner is elected with an absolute majority of the vote. This reduces the danger of spoiler candidates, increases voter choice by encouraging more candidates to enter the race without fear of splitting the vote, and requires the final contenders to construct broadly palatable platforms. This last element can prove pivotal in keeping the presidency out of the hands of extremists, who struggle with building coalitions outside of their bases. In fact, two-round systems around the world have done exactly this. In France, the system has twice (in 2002 and 2017) enabled voters to rally around a centrist candidate in the second round, resulting in landslide victories against far-right nationalist candidates who nearly achieved an absolute majority of votes in the first round. While alarming, the looming prospect of a Bolsonaro presidency is a symptom of the depth of Brazil’s crisis, not an indictment of the two-round system.

3. The Compulsory Vote

The compulsory vote is one of the most polarizing features of Brazil’s electoral system, both among Brazilian voters and electoral experts. All literate citizens of voting age are required to vote. Brazil is one of a handful of countries that allows 16- and 17 year-olds to vote, albeit optionally. Voting is also optional for seniors over seventy. Voters can cast blank or “null” votes to express anger with the system, dissatisfaction with the choice of candidates, or just for the sake of it. Still, protest voters remain active participants in democracy. The compulsory vote is only moderately enforced. No-show voters can pay a fine and explain their absence to avoid the worst consequences (inability to acquire a passport, obtain credit, and others). Though abstention rates reached a 20-year high, nearly 80% of Brazil’s voting age population cast a vote in Sunday’s elections. Conversely, the United States suffers from one of the worst voter turnout ratios in the developed world, with only 56% of voting-age citizens participated in the 2016 election. Former US President Barack Obama has openly advocated for compulsory voting.

The compulsory vote changes the calculus around who votes and consequently shapes candidates’ target audiences. Unlike the U.S., where likely voters tend to be richer, older, and more educated, Brazil’s poor and less-educated population have historically played kingmaker (over half of eligible Brazilian voters have not completed high school). Since 2002, the PT has ridden a tidal wave of working-class support to four consecutive presidential terms. Crucially, there is evidence that compulsory voting has actually helped make Brazil’s less-educated voters more politically aware and engaged. Additionally, while mechanisms of disenfranchisement still exist, the compulsory vote is a giant leap towards achieving universal suffrage. This contrasts with the U.S., where targeted groups in entire states are effectively disenfranchised. Thirty-three states utilize some form of voter identification law, six states do not allow people with felony convictions to vote for the rest of their lives, and every state but one requires voters to register in a process that can be confusing and discouraging. All of these policies have been shown to disproportionately depress turnout among low-income and minority voters.

On the other hand, many Brazilians resent being required to vote. In 2014, Brazilian polling firm Datafolha found that 61% of Brazilians were opposed to the compulsory vote and that 57% of Brazilians would not vote in the next election if it were not mandatory. The sharp uptick in negative responses since the same poll was carried out in 2010 suggests that much of this pessimism is not directly aimed at the compulsory vote but rather rooted in anger at the economic crisis, the Lava Jato corruption scandal, and the almost incomprehensibly unpopular President Michel Temer—who swept into power through an impeachment process decried by many as a subversion of democracy. Still, the lowest voter turnout since 1998 and the proliferation—and even electoral success—of “joke candidates” who openly make a mockery of elections indicate disillusionment with politics in general. Nonetheless, while some voters still abstain, the compulsory vote pressures all voters go to the polls. That includes the disillusioned and the uninformed—both of whom are capable of swinging elections, all while loathing the system that allows them to do so.

4. Electronic Voting

In 2000, Brazil became the first country in the world to conduct an election entirely via electronic voting (e-voting). All Brazilian voters use the same machine, known as an electronic voting machine (urna eletrônica), to cast their vote. The voting machines are designed to be easy to use for everyone, including the disabled and the illiterate. Voters first identify themselves via photo ID or fingerprint, then input a candidate’s number (widely publicized in ads, leaflets, and other campaign material), at which point the candidate’s name, party, and photo appear on the screen.

In addition to simplifying the voting process, the primary benefit of e-voting is speed. Votes are relayed almost immediately to Brasília—a monumental achievement in Brazil, where counting votes from remote locations, such as municipalities deep in the Amazon, can be an expensive and time-consuming endeavor. E-voting also removes the manual process of counting and re-counting votes that can take days or even weeks. Notoriously, the 2000 American election was not decided until a full month after election day since the extremely close vote resulted in a series of recounts that never produced a clear winner. Eighteen years later, some Americans still consider this election to be illegitimate. The issues with this election—non-standardized, confusing ballots and a long, mistake-prone vote counting process—are exactly what Brazil’s e-voting system aims to resolve.

Massive cyber attacks in recent years have demonstrated that digital systems, no matter how secure, are vulnerable to manipulation. While no major incidents have been documented yet, the electronic voting machines are not immune. Critics argue that the potential costs of such an attack are simply too high to risk. Furthermore, a 2015 reform that would require the voting machines to store printed paper copies of votes was suspended by the Supreme Court in 2018 due to concerns over potentially compromising voter privacy. Therefore, Brazil’s e-voting system produces no verifiable paper trail, increasing the risk that vote manipulation could go completely undetected. In the absence of evidence to support such a claim, Bolsonaro has attacked e-voting as a fraudulent system that is rigged to hand the election to his competitors. However, it is important to distinguish attacks like these, which aim to preemptively undermine the legitimacy of the election’s outcome, from legitimate grievances with e-voting.

5. Centralized, Highly Regulated Campaigns: The Corporate Donation Ban and Election-Related Programming

Brazilian elections are heavily regulated by the Superior Electoral Court (TSE), a federal agency that oversees all aspects of elections, from campaign finance to the distribution of voting machines across the country. Campaign regulation in Brazil differs greatly from the hands-off approach in the United States. However, we will focus on two of the most prominent differences between the two systems: the ban on corporate donations and election-related television programming.

In Brazil’s 2014 elections, approximately 76% of the R$3 billion (US$810.5 million) donated to presidential and congressional campaigns came from corporations. Following a 2015 Supreme Court ruling, 2018’s elections will feature zero. This experiment has faced plenty of criticism: as a result of 75% of the funding pool drying up, campaigns are financed by a combination of public money and donations. Business interests continue to influence the election via wealthy individual donors, and low and middle-income candidates face an uphill climb—competing against campaigns financed by affluent candidates themselves or by powerful institutions like evangelical churches. However, these difficulties do not necessarily represent failures of a corporate donation-free election. Rather, they demonstrate the incomplete nature of the current law and shine a spotlight on opportunities. In 2017, Congress passed a bill containing an absolute cap on individual donations (the current law limits to 10% of individuals’ annual salaries), though this was ultimately vetoed by President Temer. Additionally, Marcelo Freixo’s wholly-crowdfunded 2016 mayoral campaign in Rio de Janeiro demonstrated the viability of alternative sources of fundraising.

Through a system that regulates election-related programming (horário eleitoral), Brazilian television and radio stations must set aside fixed time for political advertising, during which candidates’ ads are transmitted back-to-back twice per day. All candidates receive a small amount of time, but additional time is distributed based on the number of seats the candidate’s party holds in Congress. The influence of election-related programming is fading, particularly in light of the meteoric rise of social media (WhatsApp—used by 120 million Brazilians, approximately 60% of the population—has become an essential campaign tool but also a dangerous enabler of viral fake news). Bolsonaro won 46% of votes in the first round despite only receiving 8 seconds of fixed advertising time plus eleven 30- or 60-second “insertions” during regular programming. In contrast, candidate Geraldo Alckmin—who received nearly six straight minutes of fixed time (nearly half of the total time allotted to all presidential candidates) plus 434 insertions—earned less than 5% of the first-round vote. However, television, whether advertising or news coverage, continues to draw eyes. Nearly 25% of the Brazilian population watched recent TV Globo interviews featuring Bolsonaro and Haddad. Social media is the political battleground of both the present and future, but television still holds the power to make or break candidates.

Lessons from Brazil

Brazil’s young democracy has stumbled under the weight of corruption, recession, and an extremely unpopular incumbent administration with an approval rate that sunk below 3% in 2018. Certainly, significant blame rests on a complex electoral system that reduces consensus-building to a grueling slog. However, concluding that Brazil’s political crisis boils down to the argument that “the system is broken” is not useful—not for building a better Brazil, and not for applying these lessons to electoral systems around the globe. Some elements work and some have failed. For many Brazilians and international observers, the jury is still out.

While flawed, Brazil’s compulsory vote and e-voting systems seek to promote the ideal of poor, underserved communities receiving a fair vote. The two-round runoff creates a very high hurdle for extremist candidates, albeit one that Bolsonaro may clear. The ban on corporate donations, while not a comprehensive solution, is a progressive step in diluting the influence of business interests on politics.

American democracy is similarly suffering from a crisis of conscience. President Donald Trump’s shock 2016 victory and decades of voter lethargy have exposed not only latent fury but also systemic flaws in how the U.S. elects its leaders. As future generations of lawmakers and voters seek remedies, it is critical that they observe the examples of others, rather than start from scratch. Look south—paradoxically perplexing, flawed, and innovative at the same time, Brazil holds lessons for the world.