In Rio de Janeiro, three black women from favelas who had worked for Marielle Franco prior to her assassination were elected as state representatives: Renata Souza (PSOL), a postdoctoral researcher in media and resistance against militarization and resident of the Maré favela; Mônica Francisco (PSOL), a social scientist, evangelical pastor, and activist from the Borel favela; and Dani Monteiro (PSOL), a young activist and social sciences student from the São Carlos favela. Also elected were Talíria Petrone (PSOL)—a black woman, public school teacher, and close friend of Marielle—and Benedita da Silva (PT) from the Chapéu Mangueira favela, the first black woman to occupy a seat in Rio’s City Council (in 1982), the only black woman elected to the Senate (in 1994), and the first black woman in Brazil to serve as governor (in 2002).

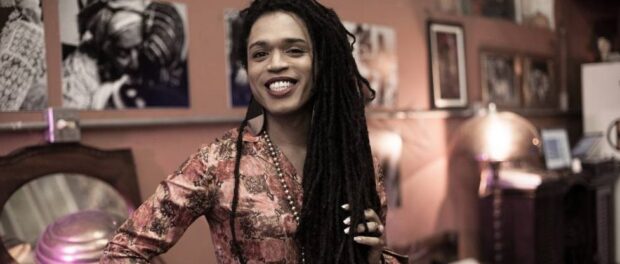

In São Paulo, Erica Malunguinho (PSOL) became the first trans woman elected as state deputy in Brazil. Malunguinho is also a black woman from Brazil’s northeast and the founder of cultural and political center Aparelha Luzia—a space for black resistance in downtown São Paulo, also referred to as an urban quilombo.

In Pernambuco, the collective candidacy Juntas (PSOL) gained a seat in the state legislature. As current legislation does not yet allow for collective candidacies, Jô Cavalcanti—a street vendor and Homeless Workers’ Movement activist—registered her name as “Juntas” and campaigned with four other co-candidates, forming a predominantly black grassroots candidacy. The collective is composed of Katia Cunha, a teacher and activist for feminist and pro-union causes; Carol Vergolino, an audiovisual journalist and feminist activist; Joelma Carla da Silva, a university student and activist from rural Pernambuco; Robeyoncé Lima, a lawyer and trans woman from a community in Recife; and Cavalcanti herself.

In Minas Gerais, two black women were elected: Áurea Carolina de Freitas (PSOL) as federal deputy—being the most-voted female candidate for this office—and Andreia de Jesus (PSOL) as state deputy. In 2016, Freitas was the most-voted candidate in Belo Horizonte’s City Council election. In Roraima, Joênia Wapichana (REDE)—the country’s first indigenous female lawyer—is now also the first indigenous woman to be elected as federal deputy. Of the 513 federal deputies in Brasília, 77 female representatives were elected in total—26 more than the number elected in 2014. Among these representatives, the number of black women rose from ten to thirteen.

Despite the increase in representation, the configuration of state legislatures and federal Congress is a sad reflection of this moment of political polarization. Uncoincidentally, in the Chamber of Deputies, the two parties that secured the most seats were the Workers’ Party (PT) and the Social Liberal Party (PSL – Bolsonaro’s party) with 56 and 52 representatives, respectively. In 2014, only one representative of the PSL was elected as federal deputy. Among Rio de Janeiro’s federal congressional representatives, the most-voted candidate was Hélio Fernando Barbosa Lopes (known as Hélio Negão), a black military serviceman of the PSL—belonging to the same party as Bolsonaro, a candidate who makes openly racist statements. Despite being the most-voted candidate for this office, he only received 480 votes two years ago when running for City Council of Nova Iguaçu, a municipality [in Greater Rio] with nearly 600,000 voters. The huge vote surge of this and other PSL candidates in the final moments of the election can be attributed in perhaps large part to the strategic use of WhatsApp as a means through which to share fake stories targeted to individuals (a strategy developed with support from Steve Bannon), and the highly contradictory proximity between the two candidates can be attributed to a campaign strategy to shield Bolsonaro from denunciations of racism and appeal to black and brown voters, who comprise nearly 55% of the Brazilian population.

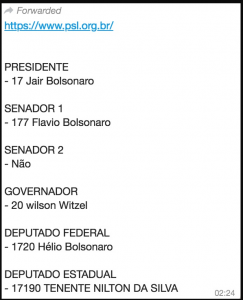

In the Senate, the parties to elect the most candidates were the Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB), the Sustainability Network (REDE), and the Progressive Party (PP), which is distinct from the current configuration in which Democrats (DEM), the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), and the Workers’ Party (PT) are the parties with the greatest representation. Of the 54 senators elected, seven are women but none are black women. These women will join five incumbents for a total of twelve female senators (there are currently thirteen). In Rio de Janeiro, Flávio Bolsonaro (PSL) and Arolde de Oliveira (Social Democratic Party–PSD), both supported by presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro, were elected to the Senate and will join Romário de Souza Faria (Podemos), who will serve the remaining four years of his term after failing in his attempt at Rio governor.

In the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ), there was an increase in the number of black female representatives from favelas—but the number of PSL representatives increased as well. With thirteen state deputies, PSL is the party with the greatest representation. Among the five most-voted candidates, four are from the PSL—including the single most-voted candidate, representative Rodrigo Amorim. Amorim was little-known prior to his involvement in a disgraceful act of vandalism—destroying the street sign that honored Marielle Franco—for which he gained recognition on social media. The parties with the greatest representation after PSL are DEM (six representatives), followed by MDB and PSOL (with five each). The result is a highly segmented legislature comprised of representatives from 26 parties.

For executive offices, the scenario is even more disheartening. There will be a runoff gubernatorial election in Rio. Wilson Witzel (Social Christian Party–PSC), the candidate supported by Bolsonaro, received 41% of valid votes. Bolsonaro’s support, and last-minute WhatsApp transmissions from Bolsonaro’s social media teams listing his recommended line-up, could explain the rapid and exponential growth of a candidate without any prior experience in politics and who, less than three weeks prior to the election, had secured only 2% of intended votes. Eduardo Paes (DEM), in his turn, received 20% of valid votes. On one hand, Witzel defends “protecting police officers from possible conviction“—that is, granting police more freedom to act with impunity in one of the most deadly states for black and poor people in Brazil. On the other hand, Paes authorized the aggressive eviction of countless favelas during the pre-Olympic period. Neither candidate was present at the debates with favela residents.

Witzel appeared in the media in 2013 when he ordered the arrest of protestors and demanded the de-occupation of the former Indigenous Museum, occupied by indigenous peoples who had been violently removed by police from Aldeia Maracanã. In his proposed government plan, Witzel claims that “the issue of public security needs to be a ‘police matter’ and no longer a matter of politics.” Furthermore, the candidate appeared speaking alongside the two elected PSL deputies when Marielle’s plaque was destroyed.

As for the presidential election, candidate Jair Bolsonaro proceeds to the runoff with 46% of valid votes in the first round (the first second round poll puts him at 58%). His proposals include granting legal protection for police who commit crimes while on-duty and classifying the act of residing on a property without a land title as terrorism—both of which directly threaten the bodily integrity and housing rights of favela residents. He has declared himself in favor of militias—which act violently and perpetrate crimes of extortion (and often drug trafficking as well). He has gone so far as to defend the legalization and state-sponsorship of militias, though he has toned down this discourse in recent years due to strong [public] rejection

His speeches are imbued with overt racism. Responding to a question about what he would do if one of his sons were to date a black woman, he said: “I’m not going to discuss promiscuity with anyone. I won’t run this risk. My sons were well-educated”—in an unfortunate association between promiscuity and race. He also said that he “would not board a plane piloted by a beneficiary of affirmative action, nor would he be willing to undergo an operation performed by such a doctor.” After visiting a quilombola community, Bolsonaro said that “the least heavy afro-descendant weighed seven arrobas (270 lbs)” and that the residents “do nothing—they’re not even good for procreation.” He has said that if elected, he will eliminate protections for indigenous and quilombola territories.

Furthermore, his discourse on social activism is alarming. In a video commentary on the first-round election results, he said that he will put an end to social activism in Brazil, threatening civil society. This sector’s most important work involves monitoring, addressing, and demanding government transparency and promoting human rights, including preventing and denouncing rights violations committed against favela residents. He has also said that he will withdraw Brazil from the United Nations, an international organization that brings together all nations and broadly aims to promote cooperation, including around issues of international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and world peace.

With a scarcity of proposals in both his governance plan (which is more antagonistic than proactive) and in his discourse (he didn’t participate in debates), it’s possible to argue that Bolsonaro’s popularity among voters stems less from his proposals and more from what he represents. We are already seeing the effects of what a possible Bolsonaro presidency represents and licenses—before he has even been elected. On the night following the first election, composer and capoeira master Moa do Katendê was stabbed to death by a Bolsonaro supporter in a political discussion in Bahia. During the campaign in a São Paulo metro station, supporters chanted to their opponents that Bolsonaro plans to kill LGBT persons.

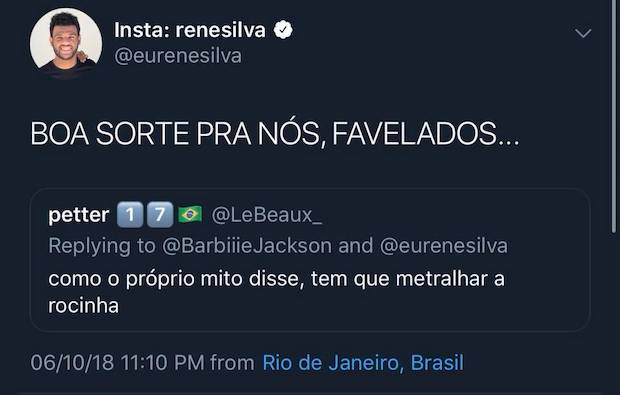

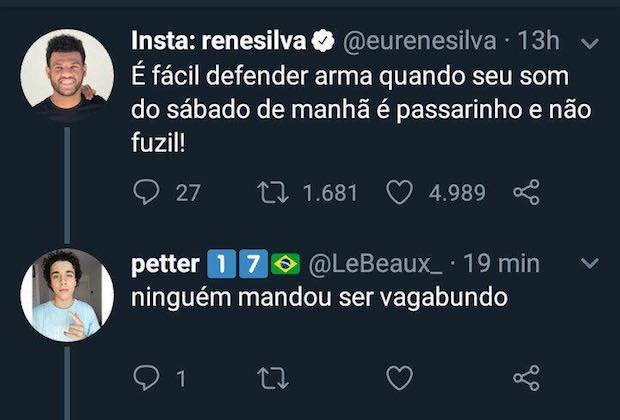

Attacks on favelas and favela residents—which are being legitimized by this candidate—can be exemplified in the following exchange on Twitter, in which a supporter echoes Bolsonaro’s promise to gun down Rocinha if criminals fail to surrender and blames a favela resident’s supposed lack of willingness to work as the cause of shootouts near his house. The resident in question is Rene Silva, a resident of Complexo do Alemão and founder of the alternative media outlet Voz das Comunidades. Silva was recently recognized in New York as one of the 100 Most Influential People of African Descent Under 40, a prize awarded to Taís Araújo and Lázaro Ramos last year.

Some maintain that a president cannot enact laws alone and that if elected, Bolsonaro would not be capable of passing his most extremist ideas through Congress. This belief should be revisited in times of polarization and in light of the new configuration of Congress, with significant representation from his own party.