This article is the first in a two-part series in which representatives and residents of the Baixada Fluminense region of Greater Rio de Janeiro analyze the security policy tendencies of Governor Wilson Witzel, who took office on January 1, 2019. For part two click here.

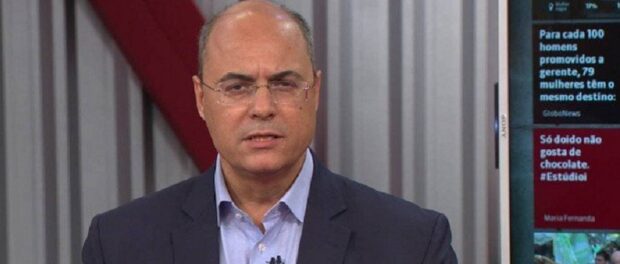

The victory of Rio de Janeiro State’s new governor, Wilson Witzel, a former federal judge who won precisely 4,675,355 votes, has sparked a series of concerns, especially when it comes to his plans for public security. As a candidate he was previously unknown to the majority of the population and never received more than one percent in the opinion polls. He stated in no uncertain terms his intention to implement public security policies “with pragmatism,” so that, besides many other anomalies, government agents would be granted permission to kill opponents if they felt threatened. The impact of Witzel’s declarations, particularly on those living in favelas and other marginalized communities who have previously suffered as a result of the abuse of power that almost always occurs when the state-run Military Police occupies their neighborhoods, is even more alarming when we taken into account that he aligned his discourse with that of the new president, Jair Bolsonaro (of the Social Liberal Party), with a clear far right stance.

What we have already seen from Witzel

One of the various actions of far-right politicians in terms of public security is the reinforcement of the conservative, traditionalist way in which legislation is drawn up, altered and even interpreted. Above all, authorizing the police to use more violent confrontation strategies and tactics. We can see an example of this in Witzel’s enthusiasm of Article 23 of Brazil’s Penal Code, which concerns exemption from criminal liability.

Two of the four paragraphs in Article 23 can be interpreted as potential justifications for an increased use of force when security agents are dealing with criminals: “The state of necessity” in which the agent “acts in order to protect his own or another’s right from immediate danger, which he did not intentionally cause and could not have avoided by any other means,” as well as “legitimate defense”—which applies to “whoever uses moderate and necessary means to fight off a wrongful assault, either immediate or imminent, on his own or another’s right.”

Various experts believe that portraying the law surrounding exemption from criminal liability as a permission guideline will help make it even easier to legally justify killing residents of poor communities when confrontations occur. Witzel recently stated in an interview that the Military Police will be able to aim their guns straight at criminals’ “stupid little heads” and shoot if they simply see that they are armed. This refuses to consider the possibility that some favela residents may simply become victims for bearing arms to defend themselves and ignores the fact that, as has already been widely reported, many residents of favelas have been killed in the past when carrying objects that were mistaken for guns.

There is a strong possibility of this happening more in the future. The new governor made a recent trip to Israel to learn about drone models that come equipped with rifles and fire at targets generated using facial recognition technology. This is a weapon that has previously been used solely in war situations. Then there’s also the lack of consideration he shows regarding the problem of prison overpopulation. With 726,000 people incarcerated and the number of prisoners almost double the number of available spaces, Brazil has the third largest prison population in the world according to the 2016 Atlas of Violence and risks seeing its already failing system collapse entirely. Yet the solution that Witzel proposes to this extremely complex problem is simple. “We dig more graves, and if we need prisons, we can put them off-shore on boats,” he said at a meeting at the headquarters of the Rio Association of Military Officers. His audience applauded wildly.

Introduction to Necropolitics

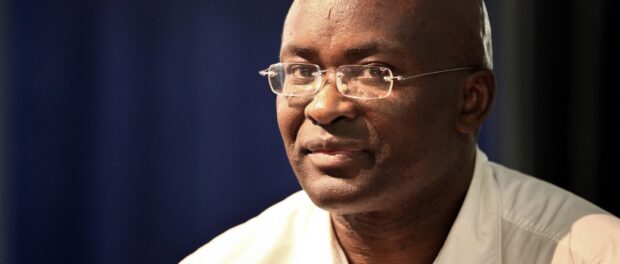

The factors discussed above, along with the institutional racism that lies behind some of these proposals, seem to suggest that Rio de Janeiro State is about to suffer from a practice known as necropolitics. The line of argument behind necropolitics was developed by Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe in an essay of the same name which made a significant impact worldwide. According to Mbembe, necropolitics is a variation on the concept of biopolitics developed by French philosopher Michel Foucault.

Biopolitics is a form of rule based around biopower, a productive power that the state or other governing body holds that is focused on prolonging, multiplying and controlling life. Under this system, life is protected because it is useful and creates value. And, in order to be useful, life needs to be regulated. However, Mbembe sees biopolitics moving ever closer to necropolitics, which is instead based around the power to take away life, insofar as individuals become superfluous, meaning that their labor is no longer profitable and they are therefore unnecessary for the generation of capital.

It becomes increasingly difficult to reconcile the power and right to cause death with the power to cause life. In order to decide who should live and who should die, the state assigns internal enemies, whose extermination it believes will improve the lives of others. When uncovering the racist nature of the way in which the state determines the enemy who can be killed, Mbembe writes, “in Foucault’s terms, racism is above all a technology aimed at permitting the exercise of biopower, ‘that old sovereign right of death.’ In the economy of biopower, the function of racism is to regulate the distribution of death and to make possible the murderous functions of the state. It is, he says, ‘the condition for the acceptability of putting to death’.”

Reflections from the Baixada Fluminense on the Necropolitics of Witzel’s government

In light of all this information, we asked scholars, movements, activists and inhabitants of the Baixada Fluminense and Rio de Janeiro for their analyses of the impact of the political context of Witzel’s incoming government on public security.

The executive coordinator of the Forúm Grita Baixada, sociologist Adriano de Araújo, claims that the governor’s political discourse signifies more of the same—security being regarded as a police concern, overtness and repression—going against a whole body of experience and studies that point to these strategies having a limited effect in reducing violence.

Adriano comments, “This militarized, police-like tone to the new state government’s strengthening of public security is very concerning for us. Let’s not forget that the government’s plan will see responsibility for reducing violence fall on the leaders of local police units, or, as the document states, “holding local agents accountable for the results they obtain in combat and criminal investigations, as well as for public security ratings.” This leads us to the following question – will the new government’s public policy in terms of security be to further fuel the deaths of poor, black, marginalized bodies? The answer to this question will be what determines the extent of the confrontations and challenges we will have to face more and more often as of January.”

According to Fransérgio Goulart, a historian and coordinator of a Forúm Grita Baixada project called “Right to Memory and Racial Justice”, Witzel and Bolsonaro’s public security policies are the norm in today’s world, given that capitalism operates against the background of the “deaths of undesirables.”

“As author David Harvey points out, from a capitalist perspective (which sees the rise in exploitative economic practices characterized by the privatization of state-owned companies, affordable housing and natural resources, as well as the increasing commercialization of work by means of global attacks on labor and pension laws), necropolitics will take its course, as capitalism no longer requires a workforce of the same size. This is the power to rule over life and death by robbing individuals of their political status. They use techniques and meticulously plan and develop devices to execute these politics of disappearance and death. Or rather, as a systemic way of thinking, there is no intention to control the designated bodies of the designated social groups. The process of both exploitation and the cycle in which neoliberal relations are established operate by exterminating groups which have no place in the system,” explains Fransérgio.

José Claudio Sousa Alves, a sociologist from the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro and the author of From the Barons to Extermination, a History of Violence in the Baixada, offers a much more critical analysis of the politics of death. “It seems to be an attempt to protect and preserve public security in the face of utterly stupid proposals like arming the population, using sophisticated weapons to murder people and applying the laws surrounding exclusion from criminal liability to police officers so that they can kill more people during operations, especially in the favelas, which target residents, and particularly younger ones,” says Alves. He finishes by stating that there will be “reactive outbursts” against these government proposals, in terms of increased violence, as control over weapons is lost, principally as they end up in the hands of arms dealers.

For part two click here.

This article was written by Fabio Leon and produced in partnership between RioOnWatch and Fórum Grita Baixada. Leon is a journalist and human rights activist who works as communications officer for Fórum Grita Baixada. Grita Baixada is a forum of people and organizations working in and around the Baixada Fluminense, focusing on developing strategies and initiatives in the area of public security, which is considered a necessary requirement for citizenship and realizing the right to the city. Follow the Fórum Grita Baixada on Facebook here.