“Our DNA is not only our own. It has been in contact with other bacteria for thousands of years,” explains Luana Silva dos Santos. It was so hot that late spring afternoon that several bottles of cold water were necessary for students to be able to concentrate. The group sat in front of two plastic tables. A makeshift whiteboard was mounted on the bricks in front of them. There was no breeze and students’ faces were sweaty, but that did not stop them from taking notes, asking questions and, above all, engaging in discussion.

They were on a terrace in Complexo da Maré, in the North Zone of the city, and the biology class had just begun. However, it is not a class in the traditional sense: Luana, 19, a biology student at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), refuses to be called a teacher, as does Laerte Breno, 23, a humanities student at UFRJ and founder of the UniFavela college entrance examination preparatory course. “Traditionally, the teacher is the person who has knowledge. But here it’s an exchange of knowledge in that I’m sharing knowledge with them, but I’m also learning from them,” he explains. The students agree. Natricia Rodrigues, 18, adds: “I think that since it’s a smaller and younger group, you have the opportunity to ask questions and if you’re a little shy you might feel more at home here.” Thiago Carlos, 21, confirms: “I don’t see it as a project; it’s more like a family.”

UniFavela’s motto, “Sowing the Seeds of Popular Education,” attests to the project’s fundamental principles. According to Breno, the idea behind the group is not only to teach people to read and memorize in preparation for college exams, but also to teach them to think critically about the society in which they live. “At UniFavela we see teachers who live in favelas just like we do, who are black just like us; we’re able to identify with them in a way that would not be possible at another school. There, there’s going to be an upper-class white person who we don’t identify with. Here [we] have all of this black and women’s resistance,” says 21-year-old Camila Felippe. Breno further explains that he teaches out of political conviction: “It’s a matter of my activism. Universities have a lot of upper-class people from Rio’s South Zone and we want to place people from the peripheries, from favelas [in college].” Giving private lessons to a student from the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro, Breno noticed the great discrepancy between Portuguese errors made by public and private school students: “One has a good education and the other has a poor education. It’s not their fault, it’s the fault of Brazil’s educational system.”

Within a few months, the founders of UniFavela managed to launch the community project. It began in June 2018 when one of Breno’s friends asked for his help studying a subject; Breno then invited others to join in. Since June, preparatory classes for the ENEM college entrance examination have taken place every Monday through Friday from 1:30pm to 4pm on the terrace of a student’s home in Maré. Through a Facebook group, UniFavela gained greater visibility, with fifteen to twenty students regularly participating in the classes. Since all teachers work on a volunteer basis, funding continues to be the greatest challenge. “We’re chasing after funding. We spend a lot on photocopies,” Breno says. The group tried to raise funds through an online crowdfunding campaign, asked for money on the street and on campus, and even paid a portion of the expenses out of pocket, but even so, it was necessary to improvise: “We were struggling without a whiteboard until a student gave us one.”

“We’ve had to cancel classes because of police operations. There’s another group from the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro studying all cute and everything, while here in the favela, there are people who aren’t able to study. So I think we need to resist even when we’re afraid—to go from mourning to fighting.” – Laerte Breno

Above all, Breno and his friends are concerned with future prospects. “We don’t know what we’re going to do next year, or if there will be space,” he says. “We can’t stay on our friend’s terrace forever,” he adds. UniFavela’s future is also uncertain for political reasons: “When we heard about the election results, we were shaken,” Breno says. He regrets that he has had to cancel classes several times due to police operations in Maré and fears that this may happen more frequently in the future. But the debates and discussions at UniFavela give him strength. These are the moments when he realizes that UniFavela takes the students one step further on their journey towards higher education. Or as he says: “We’re afraid, but we won’t give up. No one is going to stop our project.”

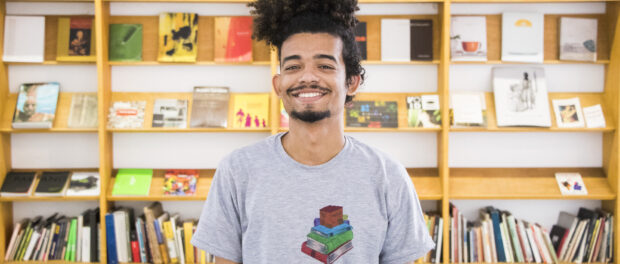

Meet Some of the 2018 UniFavela Students

“Teachers at traditional schools wouldn’t understand our reality because they weren’t trained to understand the reality of favela residents.” – Camila Felippe

“Besides learning the school subjects, we also learn about social construction—the political objectives that we believe must be defended. We also want other people to have access to college.” – Natrícia Rodrigues

“Here, the students are the teachers—we’re the same age. I don’t see it as a project but rather as a family.” – Thiago Carlos

“There’s an exchange of knowledge here. If there were a lot of people [here], I’d be shy. But not here—here, everyone’s a friend.” – Luiza Oliveira

“It’s a given that young men [from outside of favelas] will be groomed for higher education, will be able to graduate, will have a degree, and will have financial stability. That’s not the case in favelas. In favelas, there’s high school, and after that, you go to work. But community projects [like UniFavela] break this vicious circle. I think that it’s amazing.” – Cristian Gomes