For the original article in Portuguese by Flávia Medeiros published by Agência de Notícias das Favelas click here.

On January 16, Leonardo Nascimento dos Santos, a 26-year-old DJ and electrician, was wrongfully arrested when he was identified by Carla Cristina Rodrigues Santos as the man who had killed her son, 22-year-old psychology student Matheus Lessa, during an attempted robbery at a grocery store that took place the previous day in Guaratiba, in Rio’s West Zone.

On January 15, two men had, in fact, attempted to rob the market owned by Lessa’s family. Lessa came to his mother’s aid and died protecting her when he saw one of the armed robbers pointing his gun at her, ready to shoot as she tried to resist handing over the money from the cash register. However, police received an anonymous tip alerting them to the man who had actually fired the shots, Yuri Gladstone, who then confessed to the crime and also turned in his accomplice.

The only physical trait shared by the innocent man and the one responsible for the crime is the color of their skin. A side-by-side photo comparison of the two, which was publicized in the media and shared on various social media platforms, shows that they bear no resemblance to one another. However, as Santos himself acknowledged in several interviews with the press, it is difficult to imagine the pain and stress that the victim’s mother must have been going through in the wake of her son’s death. As such, her mistake isn’t all that surprising. What we should be concerned about, however, is the way in which the police conducted their investigation: two of the four people placed in the police lineup—from which witnesses were asked to identify the suspect—were white, as noted by Thiago Bottino, a professor at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, in an interview with the Fantástico team.

In an interview with Fantástico (Globo Network’s Sunday entertainment and news program), Santos tearfully told the reporter: “No one deserves to have to go through this!” Though he also said that he harbors no ill will towards the people responsible for putting him through this terrible experience, it is clear that this experience will not be easy for him to forget. He tearfully described how he was handcuffed in front of his friends standing at the gate to his house and arrested without even getting a chance to explain to his father what was happening.

The tears that streamed down the young man’s face as he recalled these events give us an idea of the scale of suffering and trauma he was subjected to. He was thrown into a cell at the Benfica penitentiary, where he was held for seven days alongside 85 other prisoners. With tears still in his eyes and his voice choked by sobs, Santos says it was “horrific.” Rumors of his “crime” had already reached his cell before his arrival, where he was then treated as though he were a monster and forced to “suffer in silence.”

But Santos’ father, convinced of his son’s innocence, managed to obtain key evidence that forced the police to admit their error: video footage showing the young man near the apartment complex where he and his family lived, located far away from the market, at the time that the crime took place. The police also received tips that helped them identify the true culprits.

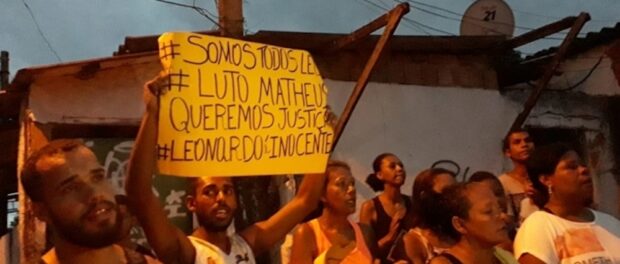

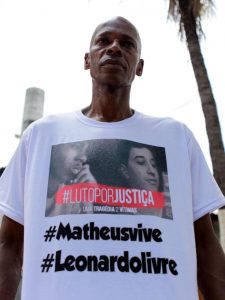

Towards the end of the night of January 23, the Rio de Janeiro Court of Justice freed Santos from the José Frederico Marques Public Jail in Benfica. In a highly emotional scene, he was embraced by friends and relatives who were waiting outside. The case ended and the young man’s record was cleared. However, others haven’t always been so lucky in the past, and without a doubt, many others will not be so lucky in the future. Let’s not forget the tragedy that befell Rafael Braga.

A Serious, Frequent Problem That Is Rarely Addressed

Cases like these occur far more frequently than they should. Actor and salesman Vinícius Romão de Souza, who was the same age as Santos at the time of his arrest, was taken in when a woman accused him of stealing from her in Méier, in Rio’s North Zone. Souza spent over two weeks in the Judge Patricia Accioly Public Jail in São Gonçalo, in Greater Rio, before being released when the true culprit was jailed. A mere Google search is enough to confirm this sad reality.

The website JusBrasil, for example, lists some of the cases in which victims have taken legal action against the government and demanded compensation. Several experts believe that financial compensation is necessary for justice to be served, but the psychological damage of incarceration—particularly for those who have committed no crime—is irreversible.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in cases of false or unjustified convictions and/or imprisonments in many countries around the world. In the United States, for example, the Innocence Project, founded in 1992, uses DNA evidence to exonerate those who have been falsely imprisoned and fights for changes to the criminal justice system in order to avoid future injustice. An increasing number of studies aim to analyze the frequency and causes of these miscarriages of justice. However, there have been few prior studies that focus on people released from jails and prisons, especially those found to have been wrongly accused.

Unfortunately, I did not find any studies dealing specifically with the psychological effects of false imprisonment on those who are locked away for a short period of time. Furthermore, in Brazil, we have to consider the fact that the problem often begins when suspects are imprisoned prior to any conviction, which the law only permits when the suspect poses a threat to police investigations. In theory, every person accused of a crime should be presumed innocent until proven guilty.

To understand what Santos might have been referring to when he talked about “suffer[ing] all this,” we can look to accounts provided by those who are or have previously been imprisoned in Brazil, in addition to studies examining individuals who have spent years behind bars until proven innocent. A 2018 study conducted by a graduate student and professors at the Augusto Motta University Center (UNISUAM) published in LexCult magazine outlined a list of “extremely serious problems within the Brazilian prison system,” which included, among many other issues, overcrowding, the unreliable fulfillment of prisoners’ basic needs, the disregard for and violation of human rights, beatings, torture, uprisings, murder, and the spread of diseases.

Even if prison conditions are decent, these innocent people are separated from their families and forced to live alongside other inmates. They risk losing their current jobs and being denied future employment opportunities, which leaves them with the feeling they no longer have future prospects. They are removed from the environments in which they previously lived—from the time, space, and social fabrics in which they were immersed. Depending on the amount of time spent behind bars, they may find that neighbors, presidents, and currencies have changed and that their loved ones have passed away.

In statements provided by those who have been released, men have reported feeling like outsiders and finding it difficult to resume relationships with family members and partners while trying to come to terms with what happened. Those interviewed by the researchers appeared to find it very difficult to identify and put into words the emotional difficulties they experienced. They feel ashamed or guilty. They avoid the subject.

Some return home in a state of agitation. Others are cold and distant towards their family members. Moreover, these nightmarish experiences have additional effects on brain function and behavior. The problem lies in the fact that the same behavior someone develops as a survival mechanism in prison will also prevent them from properly readjusting to life outside of prison. The experience is so painful and traumatic that it even affects those who have never previously experienced any psychological or psychiatric problems.

However briefly they are incarcerated, prisoners can still be stigmatized. Others may not realize that the prisoner was exonerated, or fail to believe that they were actually innocent and therefore continue punishing them in some way for simply being the victim of an error. Finally, these people have also been exposed and condemned, sometimes by national media, before they are freed. And news stories telling us that a mistake has been made tend to cause much less of a stir than stories alerting us to something or someone. Some of those who are wrongfully locked away for years end up developing much more serious mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, panic disorders, paranoid delusions, and addiction to alcohol and/or drugs.

The Disproportionate Incarceration of Black Brazilians

According to data released by the Brazilian Ministry of Justice, the incarceration rate increased by no less than 119% between 2000 and 2014. In 2000, there were 137 prisoners for every 100,000 people, while in 2014, there were 299.7 prisoners for every 100,000 people. If this terrifying trend continues at the same rate, the projections are staggering: by 2022, there will be an estimated one million prisoners in Brazil, and by 2075, over fifty years from now, one in every ten Brazilians will be in jail.

In 2014, Brazil’s prison population was 726,612 nationwide, making it the third highest in the world in absolute numbers. The top spot in this sinister ranking was occupied by the United States, which had 2,145,100 prisoners at the time, of its 318,600,000 inhabitants. In second place was China with 1,648,804 prisoners, but its overall population was 1,364,000,000, rendering Brazil’s proportional incarceration rate worse. Brazil’s prison population is predominantly composed of black people, who, according to data from the National Prison Department (DEPEN), in 2015, made up 64% of all “persons deprived of freedom,” while representing only 53% of the Brazilian population over the age of eighteen.

For those of us who are black and poor like Leonardo Nascimento, Vinícius Romão, and many others, there is always an increased risk. For example, as seen in the 2018 Atlas of Violence, published annually by the Institute of Applied Economics Research (IPEA), we continue to be the primary victims of homicide, police brutality, and injudicious and unjustifiable arrests. While we all grow up fearing police brutality and the use of excessive force by on-duty officers, for innocent people who have been falsely imprisoned, accompanying this fear is an extremely bitter memory of the experience and an indescribable feeling of pain.