On the night of March 16, twelve-year-old Kauan Noslinde Pimenta Peixoto died after being shot during a Military Police intervention in the community of Chatuba, located in the municipality of Mesquita in Greater Rio de Janeiro’s Baixada Fluminense region. According to family members, police from the 20th Military Police Battalion (Mesquita) entered the area firing. Military Police officers, on the other hand, allege that the boy had already been shot when they found him. Little publicized in the media was the fact that despite having been shot three times, the officers handcuffed the boy’s lifeless body. According to his mother, Kauan wanted to be a Military Police officer.

During the burial, his mother—under the effects of tranquilizers—became ill and was taken to the Nilópolis Urgent Care Clinic (UPA). Residents held a protest following the burial, closing off Rua Almirante Batista, where Kauan was killed.

Also in Mesquita, on May 18, 2018, Juan Henrique Amorim dos Santos was killed by a plainclothes Military Police officer, who got up from the bar where he was sitting and fired eleven shots after confusing a prank with a robbery. Less than two months prior, Juan had been mistaken for a robber after running away from a shootout and spent nearly a month in the Rio de Janeiro Department of General Socio-Educational Action (DEGASE), a juvenile detention center, before being acquitted. Friends and members of the evangelical congregation that he attended protested on social media, asserting the young man’s innocence.

His friend Carlos André Santos de Jesus, 13, who was with him at the time of the incident, was also shot by a police officer and died a week later. During the week of Carlos’ stay at the hospital, his family was prohibited from visiting him due to an alleged suspect identification—which was not formalized nor approved by the Public Prosecutor’s Office—by the widow of a slain police officer.

At the time of the crime, the boy’s father was with his son at a soccer practice just a few kilometers away. Carlos died alone in the hospital room. The time was outside of visitation hours, which are very limited for custodial cases—limited to half an hour three times per week.

On February 13 of this year, four bodies were found in Adrianópolis, a rural area in Nova Iguaçu, another municipality in the Baixada Fluminense. On the same day, four more bodies were found in Austin, Nova Iguaçu—two abandoned underneath an overpass and two in a dumpster. On March 23, yet another politician—city councilor Weldel Coelho—was assassinated in Engenheiro Pedreira, a neighborhood in Japeri. Between 2015 and 2016, fourteen candidates and politicians were assassinated in the Baixada.

The image of the Baixada Fluminense in the Brazilian public imaginary is that of a region marked by violent crime and collusion between criminals, institutional politics, and local commerce. In the context of this daily reality—which contributes to the construction of a stereotype of the Baixada Fluminense as a region composed of hostile communities—in terms of media repercussion and the number of devastated lives, nothing compares to the incident known as the Baixada Massacre. This year marks its 14th anniversary.

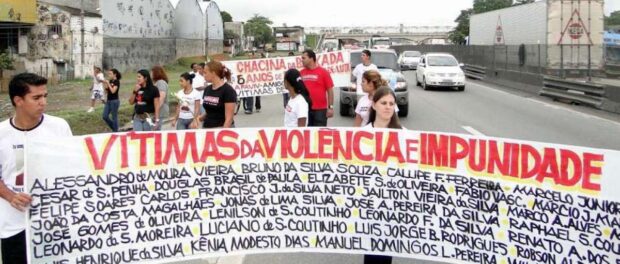

On March 31, 2005, Military Police officers killed 29 people and injured two more in several locations in Nova Iguaçu and Queimados, constituting the largest massacre in the history of the state of Rio de Janeiro. The motive involved the officers’ dissatisfaction with increased oversight due to the change in command of several police battalions in the region. Four out of five police officers who had gathered at a bar in Nova Iguaçu left by car and drove through the streets of Nova Iguaçu shooting, executing seventeen people. Thereafter, they killed twelve more in the streets of Queimados.

Since 2006, a year after the tragedy took place, activist Luciene Silva—who is now a representative of the Network of Mothers and Family Members of Victims of State Violence in the Baixada Fluminense—has organized a march along Presidente Dutra Road, passing by the location where the bodies were found. At each stop, the victims are commemorated. In recent years, other institutions and movements have joined to show solidarity in this difficult moment. The idea is not only to mourn those who were lost but also to carry out political advocacy work together with public authorities to prevent types of incidents from happening again.

In 2019, together with partners from several organizations and collectives, the Grita Baixada Forum planned a calendar of activities titled the “Week of Remembrance of the Baixada Massacre, 14 Years Later: Our Black Youth Have a Voice,” along with the traditional march.

Check out the Agenda (March 25-31):

“Our Black Youth Have a Voice” Tent

Representatives from various institutions will be available to introduce themselves. The tent is a place to speak out against violence and in favor of human rights, distribute informational materials, carry out cultural interventions, and support one another.

Date: March 25-29

Location: Rui Barbosa Square, downtown Nova Iguaçu

Time: 4pm-8pm

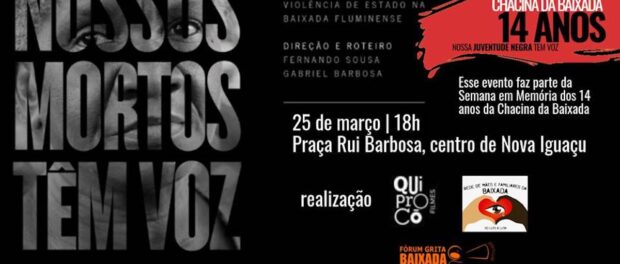

Film Screening and Discussion about the Documentary Our Dead Have a Voice

Our Dead Have a Voice is a documentary produced by Quiprocó Films. The screening is organized by the Grita Baixada Forum and the Center for Human Rights of the Nova Iguaçu Diocese. The film recounts the struggle of mothers and family members of victims of state violence.

Date: March 26

Location: Auditorium of the State Public Defender’s Office, Avenida Marechal Câmara, 314, downtown Rio de Janeiro

Time: 3pm

Interreligious Service in Memory of the Victims of the Baixada Massacre

Date: March 29

Location: Rui Barbosa Square, downtown Nova Iguaçu

Time: 6pm

Dawn for the 14th Anniversary of the Baixada Massacre – Our Black Youth Have a Voice

Date: March 30

Locations:

• Nilópolis – Calçadão de Nilópolis (Av. Mirandela, downtown Nilópolis), in front of McDonald’s

• São João de Meriti (Matriz Square)

• Duque de Caxias (to be confirmed)

Time: 9am

14th Anniversary of the Baixada Massacre March/Demonstration

Date: March 31

Location: Meeting point at Besouro Veículos (Presidente Dutra Road, 15380, near the overpass on Rua Dr. Barros Júnior, Rio de Janeiro).

Time: 9am

The following groups collectively contributed to the creation of this agenda: the Network of Mothers and Family Members of the Baixada Fluminense – RJ, the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence, the Grita Baixada Forum, the + Nós Pré-Vestibular college entrance exam preparatory course, Casa Fluminense, Amanhecer Contra a Redução (“Dawn Against the Reduction of the Age of Criminal Majority”), World Vision Brazil, Quipróquo Films, Levante Popular da Juventude (“Youth Rising”), the Federation of Social and Educational Assistance Organizations (FASE), the Favelas Observatory, the Humanitarian Center for Education, Ideas, and Alternative Training – Jardim Gramacho (CHEIFA), the Citizenship Action Commission – Nova Iguaçu, the State Truth Commission on Black Slavery in Brazil (CEVENB) of the Brazilian Order of Attorneys – Rio de Janeiro (OAB/RJ), the Rio de Janeiro Youth Forum, Movimenta Caxias, Youth Public Policy Monitoring, the São Gonçalo Baptist Community, the Kwe Cejá Gbé Candomblé House of the Djeje Mahin Nation, the Baixada Dolphins swim club, the Center for Human Rights of the Nova Iguaçu Diocese, the Pastoral Land Commission, Youca Brasil, and Redenção Baixada (“Baixada Redemption”).

This article was written by Fabio Leon and produced in partnership between RioOnWatch and the Grita Baixada Forum. Leon is a journalist and human rights activist who works as communications officer for Fórum Grita Baixada. Grita Baixada is a forum of people and organizations working in and around the Baixada Fluminense, focusing on developing strategies and initiatives in the area of public security, which is considered a necessary requirement for citizenship and realizing the right to the city. Follow the Fórum Grita Baixada on Facebook here.