For the original article in Portuguese by Júlia Dias Carneiro published by BBC News Brasil click here.

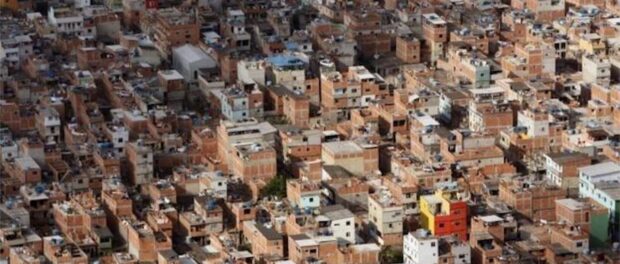

The backdrop in Rio: a shootout in broad daylight on Avenida Brasil left five injured; thirteen criminals killed in a single police operation; snipers suspected to have been shooting down into one favela; record level of police killings in 2018.

Recent levels of violence in Rio are reminiscent of the peak of violence in the state in the 1990s—when murder rates reached 64.8 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, much higher than the 2018 rate of 39.3.

It was during the 1990s, 22 years ago to be precise, that Ignacio Cano moved to Rio de Janeiro from Madrid. Cano is the coordinator of the Violence Analysis Laboratory at the Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) and has become one of the most important public security experts in Rio.

In an interview with BBC News Brasil, Cano highlighted the fact that the violence in Rio in the 1990s was still seen as a vestige of Brazil’s military dictatorship. The recent surge in violence in the city is all the more discouraging given the reversal of the progress that had been made, with a “severe regression from 2013 to the present day” following a period in which crime rates had declined.

According to Cano, Rio and Brazil are experiencing a “retreat from rights” with public security policies that make individuals responsible for their own protection—guaranteeing greater access to guns—and rhetoric that incentivizes police lethality at both the state level by Rio Governor Wilson Witzel and the federal level by President Jair Bolsonaro.

“I think we are facing a great defeat of this civilizing project,” says Cano. “For us and some of the more open-minded sectors of the police, the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) program was an opportunity to change the security model—leaving behind the old model of confrontation and trying to turn towards a protection-based model, aiming at harm reduction and minimizing confrontations. This didn’t happen and now we’re seeing a cyclic return to old policies of confrontation.”

Check out key excerpts from the interview below.

BBC News Brasil: You moved to Rio at the end of the 1990s, a decade in which the state of Rio saw a peak in the number of homicides. Does it feel like we’re back in the 1990s today?

Ignacio Cano: In the 1990s, the situation was heavy but the big difference is that we thought that this was a vestige of the dictatorship. General Nilton Cerqueira (the head of the operation that killed leftist activist Carlos Lamarca during the dictatorship) was Rio’s Secretary of Public Security. There were also some barbaric policies in place, such as “Wild West payments“—a financial reward given to police officers for fighting suspected criminals—which served to incentivize police killings.

This all seemed like remnants of another era—the dictatorship—which we still hadn’t gotten over. We thought that this period would end, that it was already on the way out.

But there has been a major regression from 2013 to the present day. The advances we made have been lost. We lost the rhetorical battle, we lost the public policies, and now we’re witnessing the defeat of all the progress that we saw over the period leading up to 2013.

Today more than ever, we’re seeing the ethos of “killing as many people as possible” in effect. I think that politicians like Bolsonaro and Witzel are focused on the idea that we can only solve the problem by killing as many criminals as possible, which is connected to the idea of “Wild West payments.”

BBC: In the current political scenario, do you see the police being encouraged to kill criminals rather than arrest them? Is this a return to something like “Wild West payments”?

Cano: Well, right now the government doesn’t have the money to offer financial rewards to police officers, but I think that there will be a symbolic prize-giving of sorts. The police are clearly being encouraged to kill more people; last year was record-breaking in terms of the number of police killings.

The big paradox is that the policies that are being proposed at the state and federal levels are being sold as something new when in reality, they’re far from new. Gun ownership has already been growing a lot in recent years. Police killings are at a record high. Politicians are selling these ideas as if they were new ones.

They rhetorically construct us—experts, members of civil society, human rights defenders, etc.—as enemies, as if we had actually managed to implement the policies that we’ve been calling for, something that we’ve never come close to achieving.

I think that we are experiencing the great defeat of this “civilizing project.” For us and for some of the more open-minded sectors of the police, the UPP program was an opportunity to change the security model—leaving behind the old model of confrontation and trying to turn towards a protection-based model, aiming at harm reduction and minimizing confrontations. This didn’t happen and now we’re seeing a cyclical return to old policies of confrontation.

BBC: In February, a police operation in Morro do Fallet-Fogueteiro [a favela in Central Rio] left 13 dead. The Military Police stated that criminals were killed in a confrontation, but their families decry executions and torture. What is your analysis of the case?

Cano: It’s a very symbolic case, with 13 people killed—the same number of people killed in the Nova Brasília massacres of 1994 and 1995 (26 people were killed in total during these two massacres in Rio’s North Zone). In 2017, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights declared Brazil responsible for having failed to guarantee justice for the victims and ordered investigations into the massacres, which are still to be carried out.

This operation, which came at the beginning of the new administration’s term, symbolizes a policy of extermination that has been openly defended by both the governor and the president—the old policy of “a good thug is a dead thug.” The fact that the governor stated that the act was legitimate before the investigation had concluded indicates a retreat from rights.

The evidence that some of the boys were tortured is extremely serious—it even counters the absurd argument that police have the right to kill because torture is a different crime than murder.

It’s an extremely serious case. The onus is on the Public Prosecutor’s Office to follow the investigations and assign blame if it is confirmed that torture and summary executions took place.

BBC: Governor Wilson Witzel is trying to abolish the Ministry of Public Security. Could this accentuate divisions between the Civil Police and the Military Police?

Cano: Witzel claims that without the Ministry of Public Security, the police would be able to regain their autonomy and get on with their jobs—as if the police used to be repressed by the Public Prosecutor’s Office. That’s false. Anyone who follows the security situation in Brazil knows that the Ministry of Public Security has very little control. The different police forces in Rio have an extremely high degree of autonomy and they don’t work together.

This idea of the “politics of chaos” has two beneficiaries. The first is the autonomy of police forces, which is already high and will increase. Civil Police officers work for the Civil Police and Military Police officers work for the Military Police.

The other beneficiary is corruption. Corrupt police officers and [vigilante off-duty police] militias love it when politicians say that from now on there will be no more interference and that extrajudicial killings will no longer be investigated. Is there anything better for a militia to hear? From now on it’s going to be enough just to say that someone was shot during a confrontation. It’s very dangerous, what’s going on in terms of the lack of control and the detrimental effects that this could cause.

BBC: The military intervention in Rio’s public security was sanctioned one year ago by former president Michel Temer and concluded at the end of Temer’s term. What effect did it have?

Cano: The intervention was an attempt at a political operation designed to garner support for [former Minister of Public Security] Raul Jungmann and Michel Temer at a time when they had no support at all. This political strategy was a failure. Neither of them managed to create a political project through the intervention.

The federal intervention did manage to reduce cargo theft but the number of police killings rose. Basically, the military intervention resulted in inertia—[crime rates] remained constant, except for cargo theft.

I think that at the very least, the intervention should have shown people that the army is not going to magically solve Rio’s security problems. However, there were high levels of public support for the military intervention.

BBC: Police killings reached a record high of 1,532 last year, compared to 1,127 police killings in 2017. What caused this increase?

Cano: It was clearly the directives of the federal intervention, the public discourse of saying that police killings were not homicides, and the attempt to change the way that these figures were counted (during the military intervention, former Secretary of Public Security Richard Nunes created a working group to modify the way homicides resulting from police intervention were counted with the aim of classifying “self-defense” cases separately). There were signs that this was the way that things were going to continue.

BBC: How important is rhetoric for public security policies?

Cano: Very important. Local rhetoric is what counts the most. What the police commander tells his battalion is the most important thing of all. Rhetoric from the central level is important, but rhetoric within local battalions is the most critical.

When Bolsonaro visits the headquarters of the Military Police’s Special Operations Battalion (BOPE) and declares that the captains are going to be in charge, this is a poisonous thing to say. In police units, it’s interpreted as: “Now it’s up to us. The commanders are no longer going to decide what we do.”

BBC: Do you think that the current context is allowing for an expansion of militia activity?

Cano: This current phase is extremely dangerous in terms of facilitating the development of militias in a context characterized by a lack of control in which investigations are not carried out.

When the federal intervention began, the discourse was that Rio de Janeiro’s police forces were out of control and it was necessary for the army to regain control. Now we have the opposite message. The police will be let loose. Not just the police officers, but police captains too. I think that this is extremely dangerous in terms of what it could mean for the expansion of militias.

BBC: In January, it came to light that during his term as a Rio state representative, Flávio Bolsonaro had employed the mother and the wife of a militia member (who has been at large since January) identified by the Public Defender’s Office as one of the leaders of the Crime Bureau, a death squad in Rio. Flávio Bolsonaro bestowed honors on him and other militia members in the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ) and later defended himself by saying that he was not responsible for his cabinet appointments and that he had already honored hundreds of police officers during his political career. Do these revelations worry you?

Cano: I think that the honors bestowed on police officers involved in militias are concerning—but given that Flávio Bolsonaro has given such honors to many other police officers, this doesn’t necessarily mean that he supports the militia. However, I am more worried about past statements by Flávio and his father [Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro] that openly show support for militias and about the fact that Flávio employed people who are directly connected to militias.

He cannot argue that these appointments were made by anyone else. All representatives are directly responsible for their cabinet appointments. Employing people directly linked to militia members would seriously compromise any representative—in this case, now-senator Flávio Bolsonaro.

BBC: Judge Sérgio Moro has presented a package of anti-crime proposals that would increase police immunity from prosecution by classifying police killings as acts of “legitimate self-defense.” This was one of the key aspects of Bolsonaro’s presidential campaign. What do you think of Moro’s proposals?

Cano: The right to self-defense already exists in Brazilian law—not just for police officers but for all citizens. What the Bolsonaro administration is proposing is, in reality, a continuation of the current situation sold as though it were something new. It’s another attempt to find a legal translation of the old slogan “a good thug is a dead thug.” It’s letting the police apply the death penalty on the streets, which is barbaric.

In practice, it is extremely unlikely that a death caused by an on-duty police officer would result in a thorough investigation and, when evidence of wrongdoing is found, in a conviction. Studies show that many cases of summary executions go unpunished.

We’re not talking about police violence simply being tolerated, or permission being granted—we’re seeing open encouragement from the state government and the federal government. People argue that these proposals will allow police officers to go unpunished for this [killing people during confrontations]—that’s the legal proposal. The political proposal—the one that’s in effect on the streets—is that police officers are being encouraged to kill.

BBC: Justice Minister Sérgio Moro says that his proposals aim to clarify the law and denies that they could be seen as a carte blanche for police killings. Are there instances in which police officers could be unjustly penalized for actions taken when their lives are at risk?

Cano: That’s an absolutely fallacious argument. Police officers do have the right to defend themselves and they already exercise this right. There is no example of a case in which a police officer died because he didn’t want to fight back. It’s also not true that under current legislation, a police officer has to wait until the first shot is fired before defending themselves. There are ways of knowing that you are going to be the target of violence. If someone pulls a gun on you, you can shoot them to defend yourself. That rule doesn’t just apply to police officers—it’s for all citizens.

Another worrying aspect of Moro’s proposals is the part that says that when a judge deems a police officer to have suffered a reasonable amount of fear or violent emotion in the run-up to killing someone, he or she can reduce the sentence or choose not to apply a sentence. This leads to a great deal of legal uncertainty. The judge can decide to apply the whole sentence, or half of the sentence, or no sentence at all.

It’s a retreat from rights. Everyone can do as they like. The police can do what they want and the judge can apply whatever sentence they so choose. It’s the deterioration of legal authority over social conduct.

BBC: Does the relaxation of gun laws decreed by Bolsonaro reflect this retreat? Is this a way of outsourcing defense to citizens?

Cano: The government’s proposals involve increasing police lethality and giving guns to all citizens so that they can defend themselves as they wish. The government is giving up its protective role and leaving control in the hands of individual citizens.

We’re literally shooting ourselves in the foot—and in other parts of the body as well. When you put a gun on the market, generally, it disappears. The gun passes through many hands and many places: it’s borrowed, sold, and stolen.

Again, it’s a dialectic of chaos—and it’s very dangerous. I think that we will see a multiplication of conflicts involving firearms, accidents, and suicides—or even cases like the boy who went to school with his father’s gun and shot his classmates as we’ve seen in the United States. And whenever there’s a high-profile case involving recently purchased guns, the government will face a backlash.