On April 29, 2018, O Globo newspaper reported the burial of five victims of the massacre in Vila Operária, Duque Caxias, in Greater Rio de Janeiro’s Baixada Fluminense on the northern outskirts of Rio proper. The crime occurred on an early Saturday morning after a baile funk party. One line of investigation is that the perpetrators are members of vigilante off-duty police militias. According to officers from the homicide division of Rio’s Civil Police in the Baixada Fluminense who participated in the forensic investigation, all of the shots were fired from pistols.

On February 13 of this year, O Globo reported the murder of nine people in two massacres in Naova Iguaçu. In the neighborhood of Austin, four men were fatally shot. Two men’s bodies were abandoned below the overpass that crosses the Metropolitan Arch highway and two more were found in a nearby dumpster. Police hypothesized that the four victims had been killed in the midst of a war over control of the drug trade in Morro São Simão in Queimados. Three more men and one woman were found dead with gunshot wounds in the neighborhood of Adrianópolis.

On April 26, in yet another act of political advocacy in cooperation with public authorities, the set of institutions that form the Grita Baixada Forum (FGB) occupied the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ) to hold a public hearing on homicides and forced disappearances in the Baixada Fluminense. Weeks prior, Grita Baixada Forum affiliates met with representatives of several members of Congress (on both federal and state levels) with the aim of building a political coalition in defense of life in the Baixada Fluminense. The idea of the coalition is to promote greater understanding of relevant challenges and strategies to address homicides in the region given that the highest rates of lethal violence in the state of Rio de Janeiro are concentrated in the Baixada Fluminense.

The first to speak at the hearing was Luciene Silva, an activist from the Network of Mothers and Family Members of Victims of State Violence in the Baixada Fluminense. Silva’s son Rafael was murdered in the tragic incident known as the Baixada Massacre, during which 29 people were killed in a shooting spree committed by Military Police officers in the cities of Nova Iguaçu and Queimados on the night of March 31, 2005. The 29 victims were killed at random while sitting on their doorsteps or walking down the street. Children, students, shopkeepers, unemployed persons, public servants, painters, and waiters were among those killed.

One of Silva’s concerns, as a human rights activist, was the relativization of suffering that she and other members of the mothers’ group experience on a daily basis. “What pains me the most is knowing that there are people who still think that the killing of a black young man from the periphery means that his death was deserved—that he was a suspect. What world are we living in? Every day, we experience physical and mental pain. But now they are trying to measure our pain, which is mixed with a sense of guilt that is not our own and that should not exist,” she said.

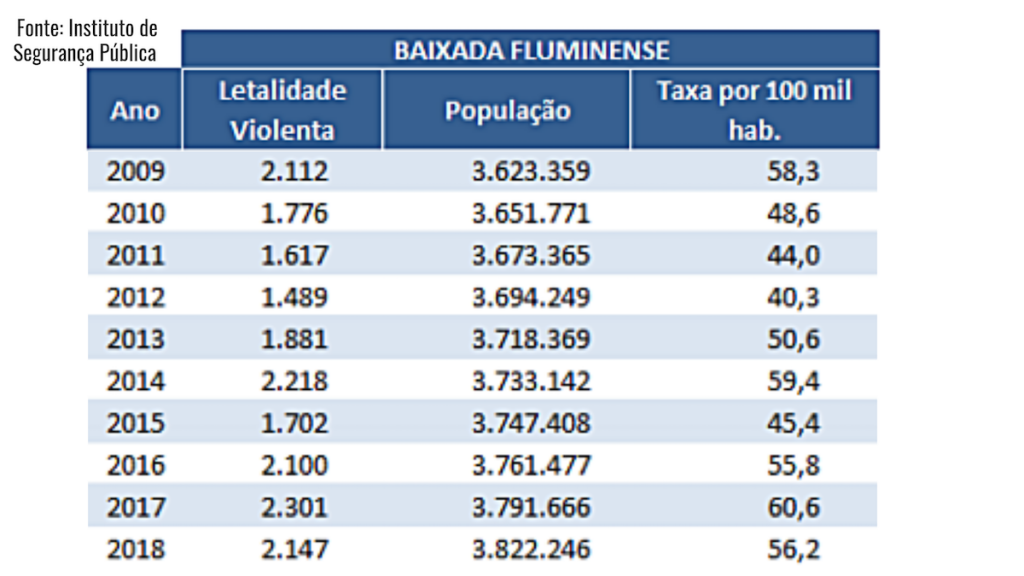

Counting all of the murders committed in the Baixada Fluminense in the past ten years, the number of victims is easily equivalent to the population of a large area. According to historical trends published by the Institute of Public Security (ISP) in March of this year, from 2009 to 2018, over 19,000 people were violently killed in the Baixada Fluminense (see table below). It’s as though the entire city of Rio Claro—located in the interior of the state of Rio de Janeiro, with 18,451 inhabitants—had been exterminated.

The truth is that the region—which is composed of thirteen municipalities, the problems of which are rendered invisible—has historically experienced violence, whether incited by drug trafficking factions or by other organized crime groups like militias. According to ISP data published last year, approximately 40% of violent deaths in the state of Rio de Janeiro during this ten-year period occurred in the Baixada Fluminense. In January of this year, the first month of governor Wilson Witzel‘s administration, the number of deaths resulting from police intervention in the region increased by 47.5% compared to January 2018. While there were forty killings in January 2018, in January 2019 there were 59. For every ten youth killed in the Baixada, seven live in favelas or other peripheries.

Daiane Lima—a community leader at the Youth Public Policy Monitoring (MJPOP) project, a methodology developed by the organization World Vision to stimulate the participation of youth in Brazilian politics—spoke about how youth from the Baixada Fluminense are directly affected by ineffective public policies that are nonparticipatory and that appear to contribute to the stagnation of this segment of the population. “The reality of black youth from the peripheries of the Baixada Fluminense is very difficult. There is a great deal of neglect as youth are neglected in culture, sports, and recreation—and increasingly, these lives are being cut short. We need to devise ways to put an end to this. We are supporting the proposals set forth by the Grita Baixada Forum and we hope to continue in the struggle for these young people’s lives,” said Lima.

State representative Dani Monteiro (Socialism and Liberty Party–PSOL)—president of ALERJ’s Special Youth Commission—argues that to speak about black youth from the peripheries is to speak about the segment of society that is rendered the most vulnerable. Born in the São Carlos favela, Monteiro—who, at just 27 years old, was elected as Rio’s youngest state representative—has been denied access to the floor of the legislature due to racism. “[Taking] the homicide rate in the state of Rio de Janeiro, for example, 53% are youth and the vast majority are black, poor, and residents of the peripheries. Eight in ten of the most dangerous municipalities [in the state of Rio] are in the Baixada Fluminense—two of which are the most dangerous in Brazil, Queimados and Japeri. The mortality rate is very high,” said Monteiro, who currently lives in Duque de Caxias, during a legislative session.

Invited to speak on a panel at the hearing, José Cláudio Sousa Alves—professor of sociology at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFFRJ) and author of the book From the Barons to Extermination: A History of Violence in the Baixada Fluminense—said that one of his greatest discomforts in attending the event was the presence of lawmakers who had bestowed awards upon militia members during their terms in office, in addition to his discomfort surrounding the government’s inaction on taking measures to reduce the power of these organized groups. “This is an abnormal country, where we have politicians who encourage and reproduce the logic of extermination, who kill Marielle and many more every day,” he said.

Alves also criticized the centralized role that the Institute of Public Security (ISP) plays in the production of data—and the accuracy thereof. “What data is this? Those who work in human rights and public security know that there is a great deal of difficulty in collecting this data because no one reports anything anymore. Police squads and precincts aren’t trusted because the poor population knows that everything is managed by militia members. The rivers and fields of the Baixada form a large clandestine cemetery,” he stated.

Commenting on the recent massacres described earlier in this article, Adriano de Araujo, executive coordinator of the Grita Baixada Forum, said that it is a cruel practice in the region—not always given exposure in the media but always felt by the local population. The Baixada Fluminense can no longer cope with so many deaths. I wonder, does the government have the means to combat the violence that it itself created?” said Araujo. He added that it is necessary to prioritize the immediate suspension of Military Police officers who are repeatedly involved in criminal acts. He also presented a set of proposals devised by this coalition of institutions for the formulation of effective public policies, including investment and new strategies to enhance the capacity of investigations into homicides and organized crime, as well as the creation of a Nucleus for Human Rights of the State Public Defender’s Office in the Baixada Fluminense.

This article was written by Fabio Leon and produced in partnership between RioOnWatch and the Grita Baixada Forum. Leon is a journalist and human rights activist who works as communications officer for Grita Baixada Forum. Grita Baixada is a forum of people and organizations working in and around the Baixada Fluminense, focusing on developing strategies and initiatives in the area of public security, which is considered a necessary requirement for citizenship and realizing the right to the city. Follow the Grita Baixada Forum on Facebook here.