For the original article in Portuguese by Felipe Betim published in El País click here.

Children from the Complexo da Maré favelas describe the horrors of life in the crossfire, writing more than 1500 letters to the Rio Court of Justice urging them to reestablish directives for police operations in Maré. In other favelas, six youth died over a period of five days.

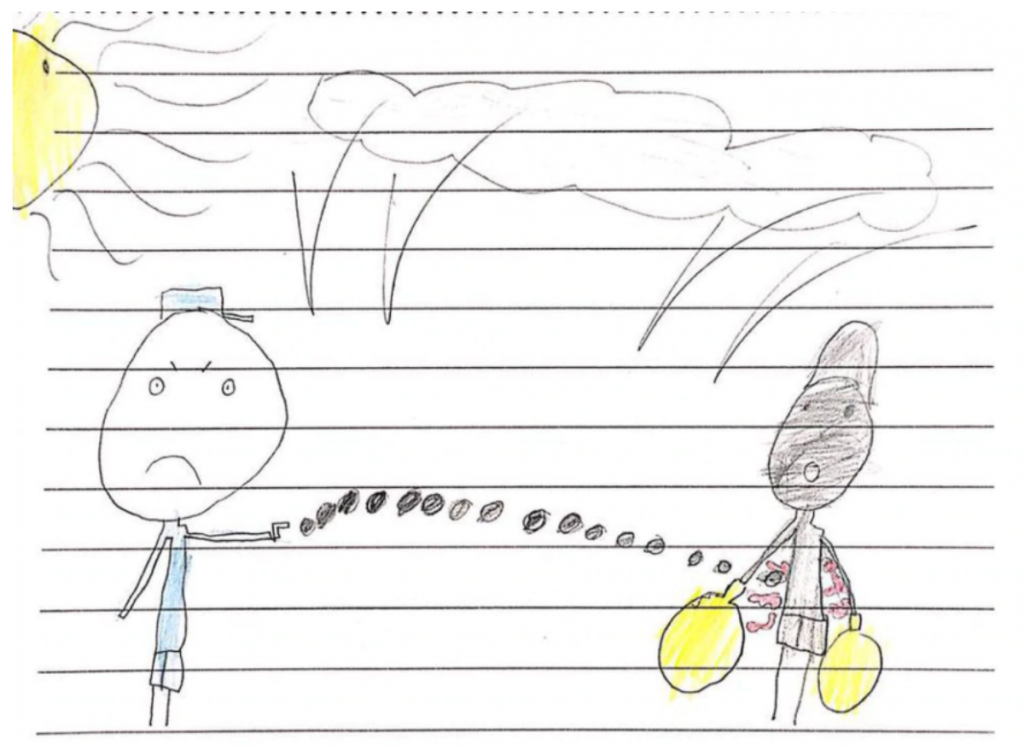

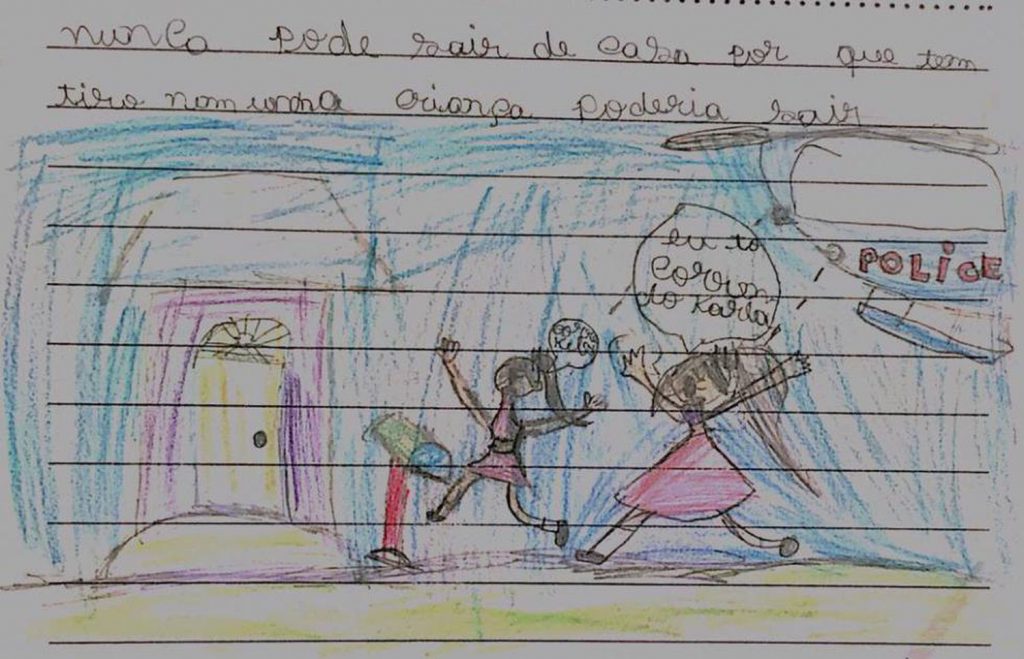

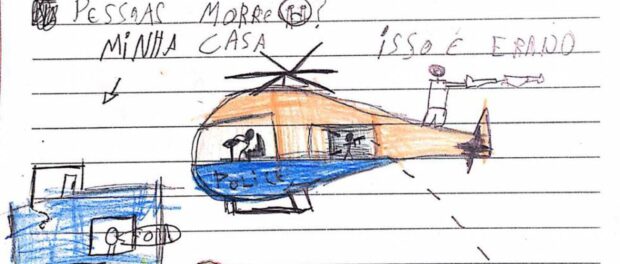

The favela bleeds. “I don’t like helicopters because they shoot down and people die,” wrote one child, whose name and age were not given, to the appellate judges at the Rio de Janeiro Court of Justice. The colored drawing accompanying the message shows a police helicopter with armed agents shooting toward the ground. There’s a drug trafficker there, but there are kids too. They run. They run in the drawing and in real life. “This is wrong,” wrote the little resident of Maré, a grouping of 16 favelas in the city’s North Zone, home to nearly 140,000. More than 1,500 letters and drawings were collected by the NGO Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré (Maré Development Networks) and sent to the Court on August 12 with a petition demanding the reinstitution of a Civil Public Action that sets limits on police operations in Maré. Accepted by the Court of Justice in mid-2017, the Action had helped reduce violence indicators throughout the following year. It was suspended in June 2019. On Wednesday, August 14, following the appeal from residents, the Action was reinstated, reestablishing minimum parameters for police actions, such as requiring the presence of an ambulance during operations and barring operations when students are on their way to and from school.

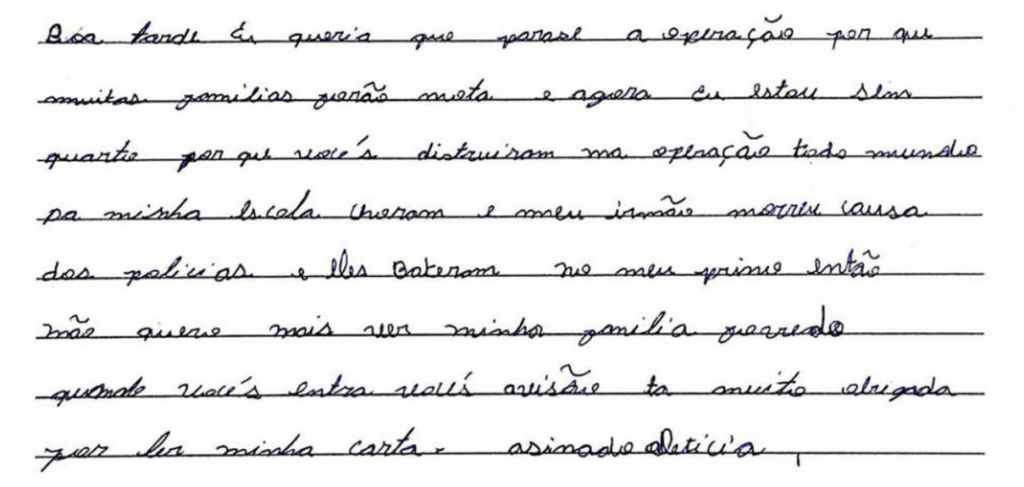

The favela cries. On that same Wednesday, it was revealed that over a period of five days, six youths between the ages of 17 and 21 were shot and killed during police operations in communities around the state of Rio. Most suspect the police. Images of Cristóvão Xavier de Brito spread throughout the country, the grandfather dressed in a t-shirt soaked in the blood of his 16-year old grandson Dyogo, who died in his arms. Dyogo was on his way to soccer practice when he was shot in the back by the police, according to witnesses. Leticia, a resident of Maré who wrote a letter to the Court, knows what it means to lose a family member. “Good afternoon, I would like the operations to stop because many families will be killed and, now, I don’t have a bedroom because you destroyed it during an operation,” she wrote. “Everyone at my school cries. My brother [cries] because of the police. They beat up my cousin. So, I don’t want to see my family dying anymore when they come in. Let me know, ok? Thank you for reading my letter. Signed, Leticia.”

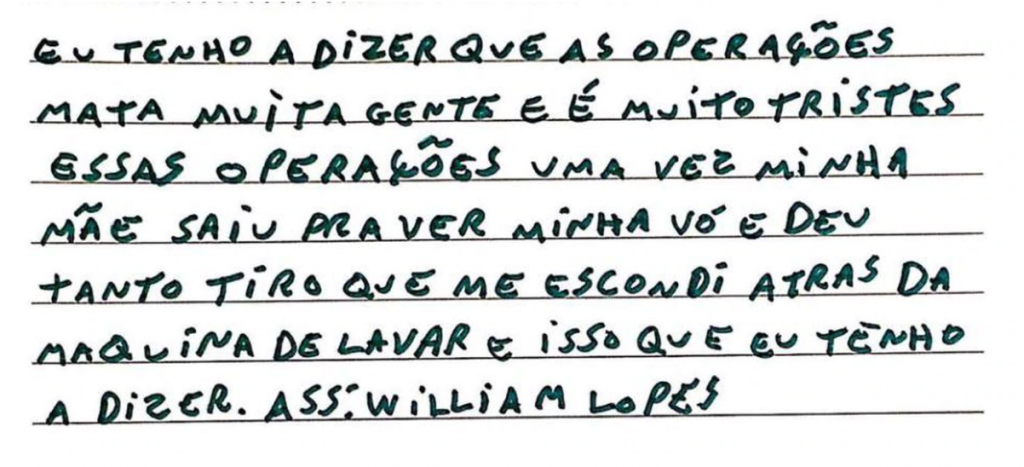

The favela counts its dead. A bi-annual bulletin published by Redes da Maré that week shows that 27 were killed in the first half of 2019 alone—10% more than all of 2018, when 24 were killed. 15 people died during 21 police operations; the other 12 died during 10 confrontations between the criminal factions that control the communities of Maré. “I have to say that the operations killed a lot of people and it is very sad,” wrote a boy named William—like the others, his letter was transcribed in type to aid the reader. Throughout 2017, before the Civil Public Action entered into effect for the first time, 42 people died (one every nine days), and 57 were wounded. In that year, 41 police operations took place, while criminal factions entered in confrontation 16 times. “One time my mother left to see my grandmother and there were so many shots that I hid behind the washing machine. This is what I have to say.”

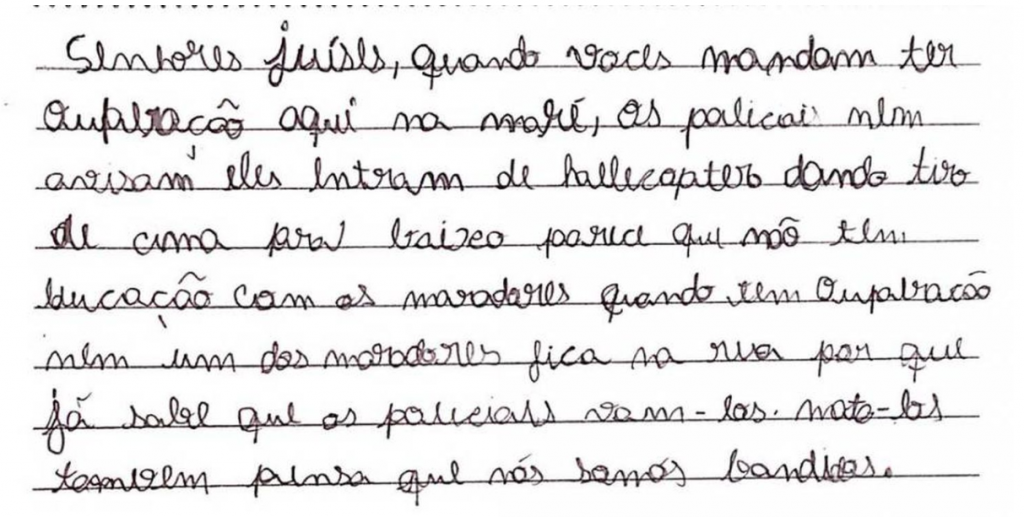

The favela is scared. And it lives through moments of real panic. According to the bulletin, four police operations used helicopters—nicknamed the caveirão voador [flying skull, a reference to the armored personnel carrier nicknamed caveirão]—as firing platforms in the first half of 2019 alone, tying the total number of instances for 2017 and 2018 combined. “Dear judges, when you order an operation here in Maré, the police don’t tell us. They come in helicopters, shooting down. It seems like they don’t respect residents,” wrote another child. Of the 15 deaths that took place on days with police operations this year, 14 occurred when a helicopter was in use. “When there is an operation, none of the residents stay in the street because they know that the police will kill them. They think we are bad guys too,” wrote the child.

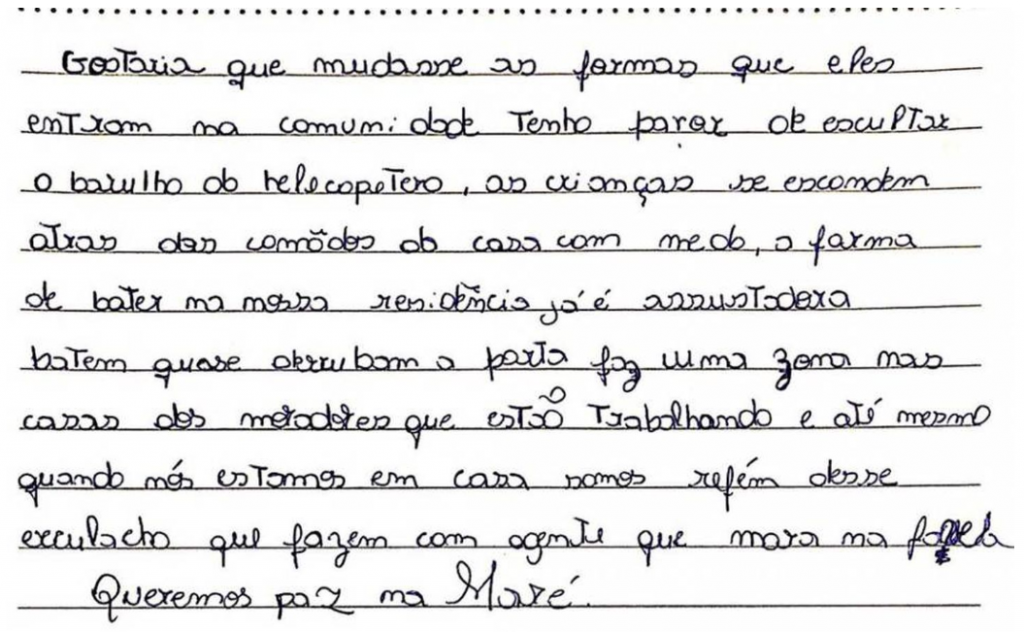

The favela is frightened. “The children get scared and hide behind the furniture in their houses. The way they knock on our doors is scary. They hit it and almost knock down the door. They make a mess of the houses of the residents who are out at work,” wrote another resident to the Rio judges. They are subjected to a range of abuses committed by the authorities. “Even when we are at home we are hostages to this abuse they inflict on us.”

The favela is the target. Wilson Witzel gave up his role as a federal judge at the beginning of 2018 in order to run for governor in that year’s general elections. He won promising to shoot criminals “in their little heads,” which has now become a sort of endless mantra, both in word and deed. Since he assumed office and began to command Rio’s Civil and Military Police, he has begun putting into practice a public policy critiqued for its tendency to stoke police violence, primarily against the black youths that live in the state’s peripheries. Witzel routinely poses for photographs alongside rifle-strapped police officers. He boarded a Civil Police helicopter in Angra dos Reis, the night before another police operation in Maré. In the helicopter, he sat alongside an agent shooting towards the ground. Witzel publicly supports this practice.

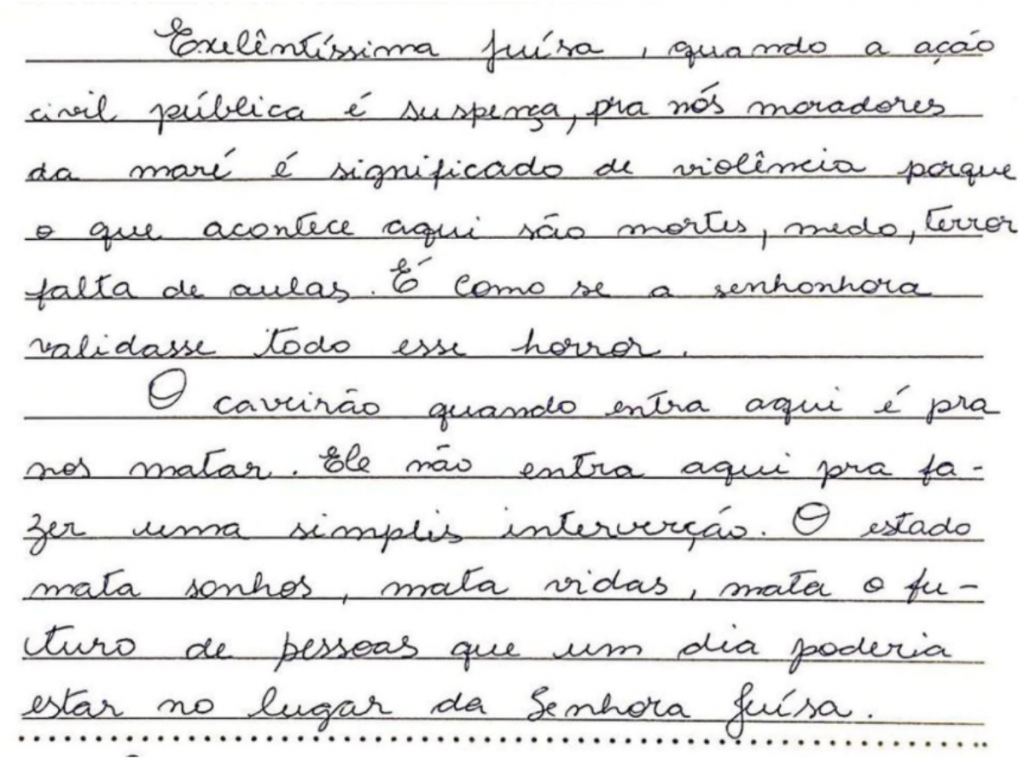

The favela is in their sights. Data from the Rio Public Security Institute (ISP), a state organ, registered 3048 violent deaths in the state of Rio de Janeiro between January and June of 2019. Out of these, 881 were murders committed by state security agents: 29%. Nearly one third. Historic records are being set month after month, and these figures do not account for murders committed by members of the militia [formed by off-duty and former security agents] or police that kill without entering their actions into the criminal registry. “The caveirão, when it comes in here, it comes to kill us. It doesn’t come here just for a simple intervention. The State kills dreams, kills lives, kills the future of people who could one day be in your place, madame judge,” wrote another resident.

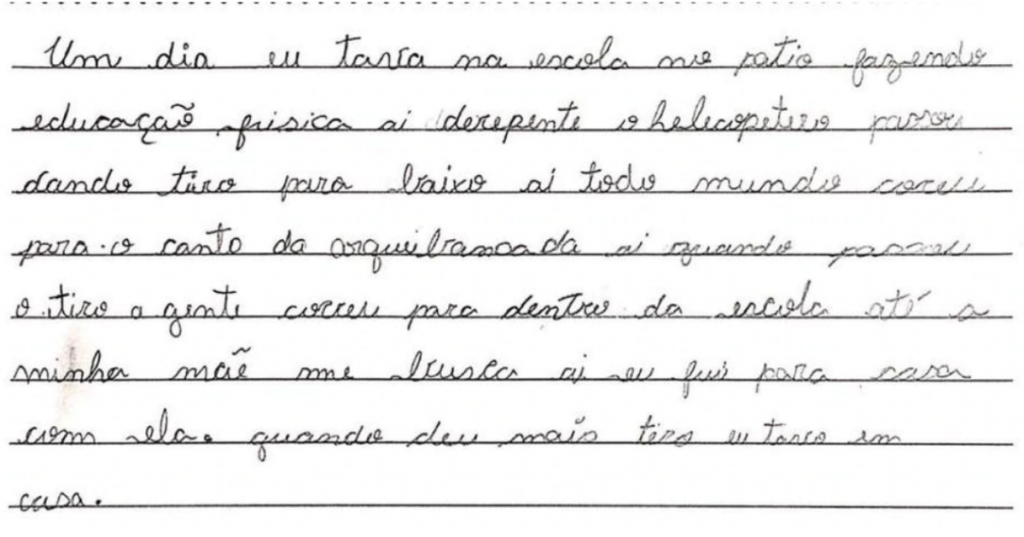

The favela goes without school and without healthcare. The bulletin from Redes da Maré states that, throughout the first half of this year, schools and health posts experienced ten days of forced closures because of shootouts, the same as the total for all of 2018. In 2017, before the institution of the Civil Public Action, children saw their classes suspended on 35 separate days, and health posts closures totaling 45 days. In that year, 41 police operations took place. “One day I was at school, outside, at P.E. class. Out of nowhere, a helicopter passed by, shooting down, and everybody ran to the bleachers,” wrote one child. “When the firing stopped, we all ran inside the school until my mom came to get me. When there are more shots, I stay at home.”

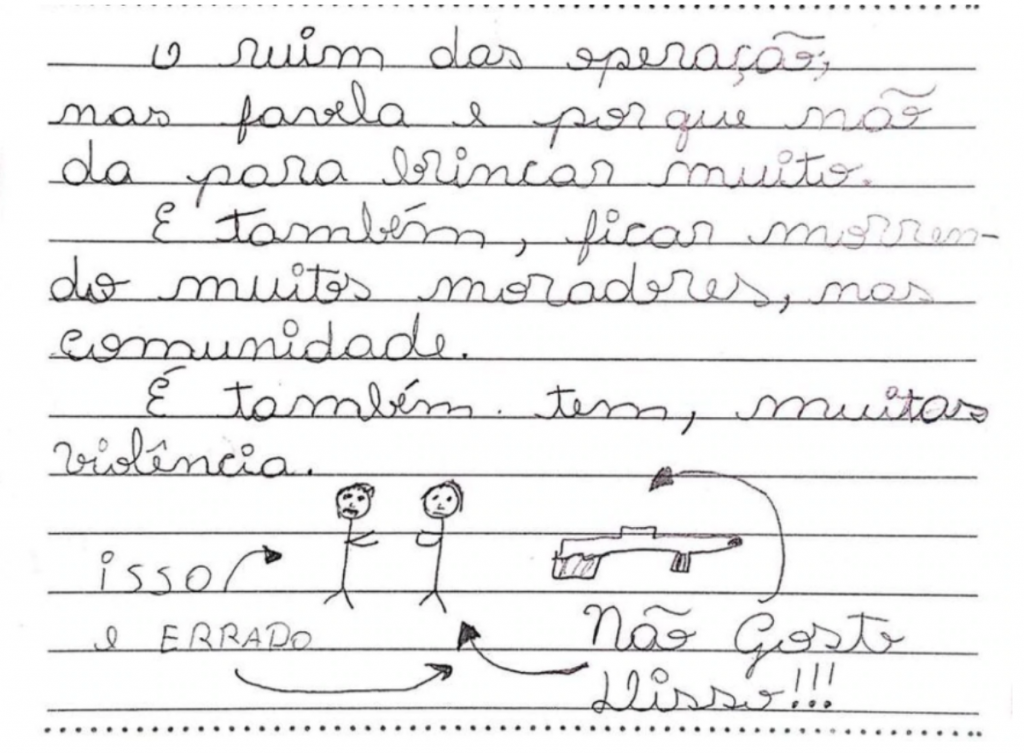

But the favela wants to play. “The bad thing about operations in the favelas is that we can’t play,” wrote another young resident. “There is a lot of violence.”

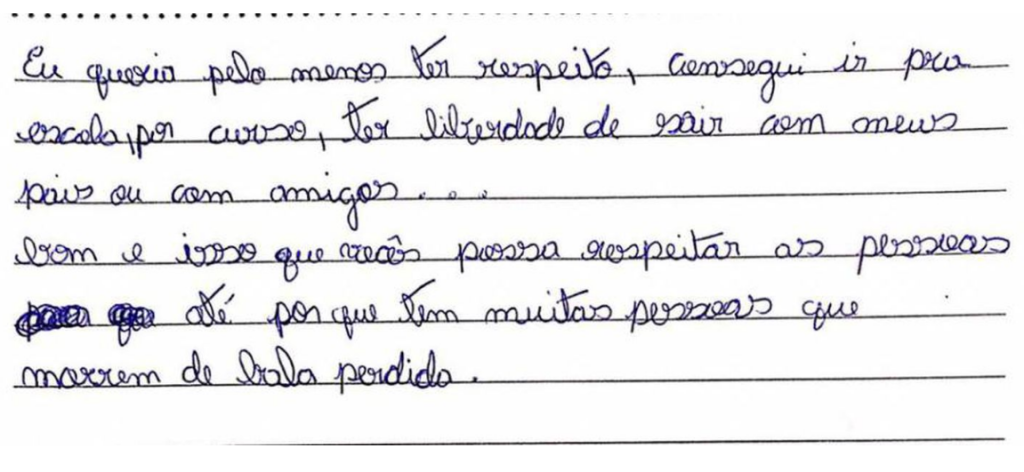

The favela wants respect and freedom. “To be able to go to school, to class, to have the freedom to go out with my parents or my friends… Well, that’s it. I wish you could respect people. Because many die from stray bullets.”

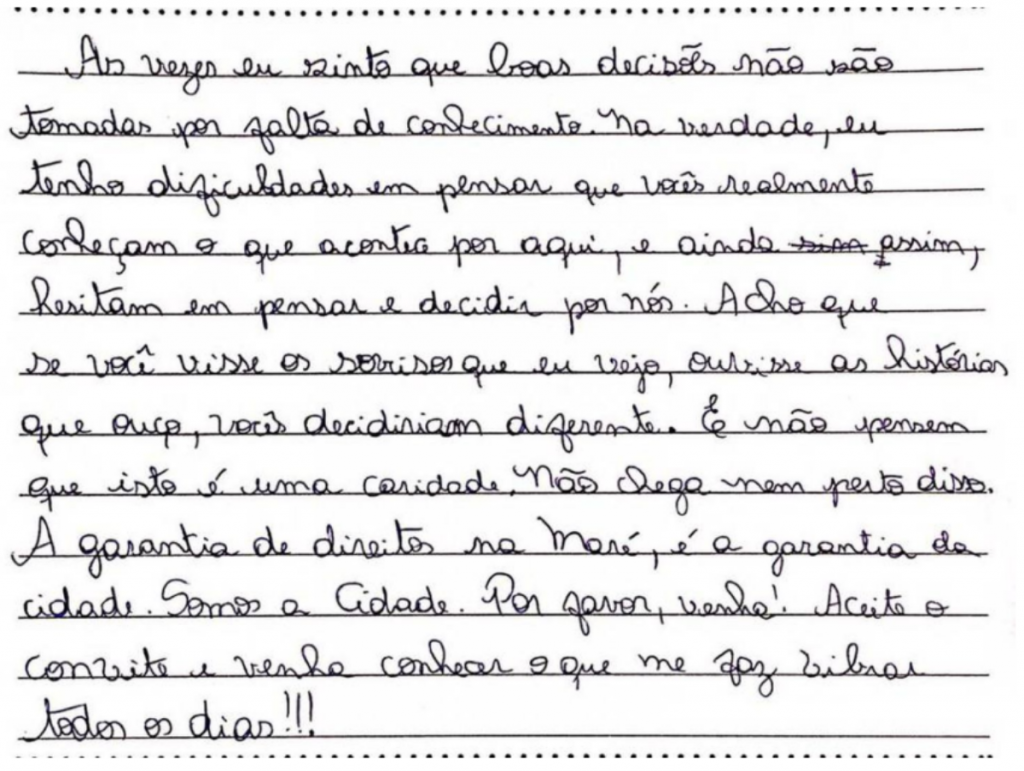

The favela wants rights. “I think that if you could see the smiles that I see, if you heard the stories that I hear, you would decide differently. And you wouldn’t think that we are asking for charity. It’s not even close,” wrote an anonymous youth. The letter ends with an invitation to the judges “Guaranteeing rights in Maré means guaranteeing rights for the city. We are the city. Please, come. Accept this invitation and come to get to know what moves me every day!!!”

The favela wants peace.