“I just want to be happy, walk with tranquility in the favela where I was born. And be proud and have the awareness that a poor person has his place… My dear authorities, I don’t know what to do anymore. With so much violence I am afraid to live. Because I live in the favela I am disrespected. Sadness and joy walk hand-in-hand… While the rich live in a beautiful house, the poor are humiliated and demoralized in the favela… All I ask of the authorities is a bit more competence.”

(Rap da Felicidade by Cidinho)

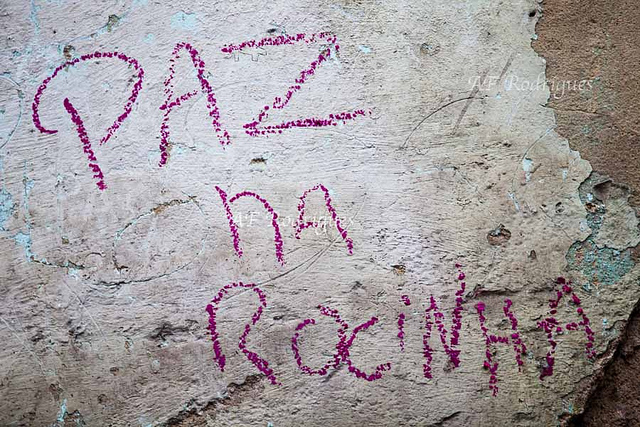

These lyrics come from a song named ‘Rap de Felicidade’ [Happiness Rap] and are written by favela resident Cidinho. In any favela I visited at some point I would hear this song playing in a little bar, echoing from a window or blaring from a car. Cidinho raps about the lack of power that favela residents have to convince the state to treat them with respect. This rap dates from 1995, a time when violence in the favelas was at a high. The lack of respect by the state towards favela residents was visible in, amongst others, the lack of access to citizenship rights. State services such as trash collection, good public schools and safety through police protection were virtually non-existent. The state was perceived to be a distant entity, whose presence materialized in the sporadic BOPE raids and the visits of politicians in election times.

The UPP (Police Pacifying Units) is the first policy that aims to permanently establish the presence of the state in the favelas. But has access to citizenship rights improved for favela inhabitants? Brazilian political scientist Maria Sadek urges us to approach citizenship from “two angles: the individual and the social.” By the individual she refers to “the bundle of rights that enable a person to participate in public life.”

Sadek relates citizenship to the amount of inequality that any society finds tolerable. This leaves the question of what constitutes a ‘tolerable’ level of inequality and perhaps more importantly, who gets to decide what constitutes tolerable and intolerable? In this day and age the state and its public policies play a large role in setting the boundaries for ‘tolerable levels of inequality.’ Yet the influence of individual citizens is increasing through various participation processes in which governance becomes a co-creation process such as can be seen in Porto Alegre. The UPP policy is presented as a policy in which citizens can participate in their outcomes.

Yet full acknowledgement of Brazilian citizens, especially favela residents, remain limited. There is still an assumption that able-minded citizens who can co-create public policies is limited to the intellectual elite. This can mainly be seen by the images invoked by the authorities to justify the violence that is part of the first phases of the UPP implementation. Politicians use hyperboles. When referring to favelas they often speak of ‘separate favela-states’ and ‘war.’ According to political scientist Mark Duffield such terms can be seen as “metaphors for the opposing characteristics of order and chaos. While the representations of borderland barbarity may help to animate (…) policy, arouse public attention or urge us into action, the borderlands do not exist in reality; they are imagined geographical space.” The question is whether this particular painting of the favelas influences the way favela residents are incorporated into the larger nation-state.

In his 2011 lecture at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Mario Sergio Brito Duarte, General Commander of the Rio de Janeiro State Military Police, explained pacification as “a pax romana, a peace that will first be implemented more harshly, until we get to the point of a negotiated peace, conflict mediation, involving all people and all social players in those [favela] regions.” Translated to the reality of the favelas this has often meant that favela residents were not treated as stakeholders with a voice until after the initial occupation phase of the UPP policy.

In his 2011 lecture at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Mario Sergio Brito Duarte, General Commander of the Rio de Janeiro State Military Police, explained pacification as “a pax romana, a peace that will first be implemented more harshly, until we get to the point of a negotiated peace, conflict mediation, involving all people and all social players in those [favela] regions.” Translated to the reality of the favelas this has often meant that favela residents were not treated as stakeholders with a voice until after the initial occupation phase of the UPP policy.

The dilemma Rio is dealing with is the careful balance between hearing all the stakeholders and taking into account their wishes whilst at the same time implementing much needed public policies in areas where the government’s daily presence has been absent for many decades. Current policymakers favor harsh peace over negotiated peace, which seems to speed up policy implementation. They argue this is vital for the first phases. But for this policy to truly bare fruit favela residents need to undergo a drastic change in their view of the state. Their view has often been colored by the neglect, or abuse, they suffered at the hands of government officials. The initial implementation phases of the UPP policy and the violence that seems to be part of it does not offer residents a different, or more positive picture of the government. The respect that favela citizens crave from the government is not only important because it is a basic requirement of a good citizen-state relation, it is also vital for the government if they want the UPP policy to have success long-term.