Despite torrential rain and severe weather warnings, the characteristically resilient residents and supporters of Rio de Janeiro’s Vila Autódromo came out in droves on March 1, packing the São José Operário Church for the official screening of three films on the West Zone neighborhood. Connected to the community’s own Evictions Museum, Vila Autódromo’s original Catholic church still sits on one of the boundaries of what is now Vila Autódromo, beneath the towering Residence Inn by Marriot, built adjacent to the original community for Rio’s 2016 Olympics. On this particular evening, however, it was the church, not the hotel, that was full of people.

Background

Until 2013, Vila Autódromo, located on the banks of the Jacarepaguá Lagoon in Rio’s West Zone, was home to roughly 700 families. Real estate speculation first threatened the 50-year-old community when the exclusive nearby Barra de Tijuca neighborhood began to expand into the area in the early 1990s. Residents responded with a successful campaign of community organization and resistance, led by the Vila Autódromo Residents, Fishermen, and Friends’ Association (Associação de Moradores, Pescadores e Amigos da Vila Autódromo, or AMPAVA), gaining 99-year concession-of-use leases from the State government to the land on which their community is located and earning temporary safety.

Until 2013, Vila Autódromo, located on the banks of the Jacarepaguá Lagoon in Rio’s West Zone, was home to roughly 700 families. Real estate speculation first threatened the 50-year-old community when the exclusive nearby Barra de Tijuca neighborhood began to expand into the area in the early 1990s. Residents responded with a successful campaign of community organization and resistance, led by the Vila Autódromo Residents, Fishermen, and Friends’ Association (Associação de Moradores, Pescadores e Amigos da Vila Autódromo, or AMPAVA), gaining 99-year concession-of-use leases from the State government to the land on which their community is located and earning temporary safety.

On October 2, 2009, however, the threat returned. Rio de Janeiro was selected to host the 2016 Olympics and then-Mayor Eduardo Paes announced that Vila Autódromo, located next-door to the future Olympic site (which would be developed into luxury condos post-Games), would be removed for the upcoming construction projects. The justifications provided by the city for removal wavered from month to month while the community’s resolve to stay was firm. From 2010 onwards, the community worked with Rio state public defenders and urban planning partners at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and Federal Fluminense University (UFF) to fight the eviction threat legally and pragmatically, even developing an award-winning People’s Plan that would allow the community to be fully upgraded and remain in place during and after the Games. The community became known internationally for its resistance over this period. Despite Vila Autódromo’s nationally and internationally recognized right to remain on their land, and diverse and creative efforts to remain, however, the City succeeded over two years to realize forced evictions and demolitions, some violent.

Of the original 700, only 20 families remained, their new houses surrounded by concrete which has since grown into empty green space where their homes, and those of their neighbors, once stood. Remaining Vila Autódromo residents remember that violent history on a daily basis, motivating their continued activism and shared community resistance. This, in turn, has inspired long-term friends and collaborators to keep coming back to the community to carry out projects such as the March 1 film screening.

Three New Films About Vila Autódromo

Between June and September of 2017, Cristina Ribas and Lucas S. Icó worked with residents of Vila Autódromo to write the book vocabularies in movement /\ lives in resistance: singularities in the struggle from conversations in Vila Autódromo. Realized in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut Rio de Janeiro and the Evictions Museum, the book functions as a map of the words used by Vila Autódromo residents to describe the community’s resistance. Summed up by Ribas and Icó as a “glossary of terms of resistance,” it serves to facilitate “discussion between past, present, and future.”

The two authors explained that the book was the starting point for a film project producing three films supported by the Le 19 Centre régional d’Art Contemporain. The two authors worked with another filmmaker, Sol Archer, to involve many of the remaining residents of Vila Autódromo on their experiences continuing the resistance. These three films were the focus of the day’s screening.

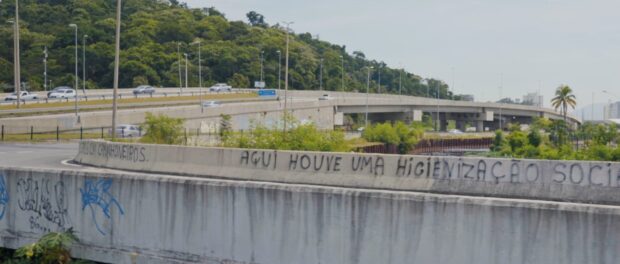

The first film, Caminhar ao Redor (Walking Around), focuses on the contrasting models of what a city is, featuring Vila Autódromo as it is today and the Olympic construction projects, also as they are today. Dynamic camera shots portray the community’s green landscape, crowded with trees. Ribas explained the aim to demonstrate that this connection between Vila Autódromo and nature plays a central part in how the community looks after and cares for the natural space, as it did in the original community. These shots are interrupted by the conflicting Olympic construction projects, namely the noise of traffic on the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) highway and the neighboring mega-hotel. Ribas explained that the visual and sonorous disruption aimed to demonstrate how these construction projects pollute the area. The film features no people, choosing instead to depict the spaces they had inhabited and from which they are now excluded.

The second film, Caminhar Pra Longe (Walking Far), follows Vila Autódromo resident Denise Costa dos Santos, one of those who successfully resisted until the end and was rehoused in one of 20 identical government-provided units on the community’s original land. In the film, Santos walks from her home to the neighboring favela of Asa Branca and into the hills beyond. Santos guides the filmmakers across busy highways and through exclusive condominiums, both of which act as an obstacle to the natural spaces Santos—undiscouraged—is trying to access.

The walk holds two special purposes for Santos. The first is therapeutic: Santos explains that she doesn’t want to be stuck in her house, and she finds walking invigorating. She says that she does this walk because of the history of Vila Autódromo and that it is therapy for the “horrors of the evictions.” Santos says that “one can’t forget the past” but that the “suffering gave [her] strength,” strength to reconnect with the space in which she lives and the land she fought for. The second is functional: Santos picks up recyclable materials that people have thrown on the ground, mainly aluminum cans and plastic bottles. She explains she has been concerned about recycling since before the evictions and is troubled by people littering. Santos had lived in the old Vila Autódromo for 26 years, and has now lived in the new Vila Autódromo for three. She says she fought a war to stay to the end and find a solution.

The third film, Memória do Teatro na Vila Autódromo (Memory of the Theater in Vila Autódromo) focuses on a theater project involving residents and the filmmakers. The film shows residents, some of whom had studied drama at an earlier stage and practiced in the community, playing and interacting through various improvisational sequences across a number of meet-ups. Luiz Claudio Silva, a long-time resident in the original community and leader in today’s Vila Autódromo, said that it is important to remind people of “the talents in the forgotten communities in the peripheries.” Ribas explains that the main objective of the meet-ups was to play through acting and enjoy the marvelous things the body can do. She also highlighted her preference for exploring the shared history of Vila Autódromo residents through the physicality of acting after the work achieved with vocabularies in movement /\ lives in resistance.

The day’s films stand as a testament to the success of Vila Autódromo, which, despite losing over 97% of its original residents, remains one of the most resilient Olympic evictions-resistance cases in history. In preserving the memory of those who lived there and the community’s struggle, founding its own museum, and maintaining a vibrant arts culture around its resilience years later, the neighborhood continues to serve as an international model for communities fighting evictions in the wake of mega-event preparations.